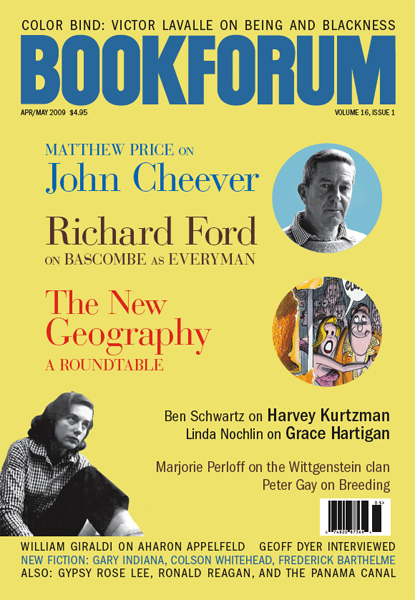

The “Message from the Author” on the advance reading copy of Sag Harbor catches the book’s tone right off the bat. “I’ve always been a bit of a plodder, which is why I now present my Autobiographical Fourth Novel, as opposed to the standard Autobiographical First Novel,” writes the author of The Intuitionist (1998), a coiled, dank existential mystery story about a war between two schools of elevator inspectors; John Henry Days (2001), in which the steel-driver ballad rewrites itself and everyone it touches; and Apex Hides the Hurt (2006), a tense tale of a New York nomenclature consultant who is brought out to a small town to rename it and in the process retraces the founding and making of America. “I recommend this approach to others,” Colson Whitehead goes on. “This country was built on innovation, after all, and just because things have been done a certain way for a long time, there’s no reason we have to keep doing them that way.”

That’s the tone: a certain archness, a touch of self-congratulation, a slipknot of a point of view (instead of following the road most taken, innovate: Follow me), and ironic capitalization. With fifteen-year-old Benji, a smart kid with braces and a job at an ice-cream shop, as our narrator, we follow the adventures of a group of teenage boys running around an African-American enclave on Long Island (“According to the world, we were the definition of paradox: black boys with beach houses”) in the summer of 1985. We hear about the Great Coca-Cola Robbery and When Dad Called Reggie Shithead for a Year, about the loser with a car and an ID (“It has been observed by wiser men than me that kids who hang out with kids who are too young for them often make themselves useful in the transportation and beer-buying sectors”), and about the UTFO show Benji and a friend talk their way into. For however long it takes you to read almost three hundred pages, you are stuck with the family albums of someone you’ve just met.

If you’ve spent days, not hours, lost in the quietly threatening worlds Whitehead creates in his unautobiographical novels, or years feeling their undertow, dragged down by protagonists whose foggy depression becomes its own gravity, then you push on through Sag Harbor in the hope of finding something to like, some sign of a novelist’s vitality, an indication that he has a story to tell, not just something to get out of his system or to keep things going while he comes up with an idea for a real novel. You do find it: riffs on insults, hexed tourist shops (“Antique stores collecting sixty years of lapses in taste vis-à-vis summer-home decoration . . . preppie clothing stores selling weird things like pre-tied sweaters—sweaters that could not be worn in the conventional fashion as they were in fact fat cotton necklaces”), the subversive power of terrible radio songs, the transition between Run-DMC and Ice Cube, and why neither Benji nor his compatriots could walk down Main Street with a watermelon under his arm, even if he had a pretty good reason:

Like, you were going to a potluck and each person had to bring an item, and your item just happened to be a watermelon, luck of the draw, and you wrote this on a sign so everyone would understand the context, and as you walked down Main Street you held the sign in one hand and the explained watermelon in the other, all casual, perhaps nodding between the watermelon and the sign for extra emphasis if you made eye contact. This would not happen.

It’s a writer digging into a moment, wondering how it works, pushing it past worry and fantasy into a land of explained watermelons that would not exist had not the writer, this one, not someone else, stumbled on it and decided to investigate. But there’s not nearly enough. Instead there’s the laziness of a writer whose story is so familiar he doesn’t have to search for its real words but can instead plug in those of anybody else (“on the same page,” “cut to,” “bottom line,” “no brainer,” “tipping point”) and leave behind such sentences as “Over the years I have learned that the sunrises and sunsets of that beach are rare and astonishing but I did not know this then.” The writer doesn’t know it now, not if he thinks you can throw in astonishing after another adjective—the socks are well-made, inexpensive, and astonishing—and have a reader believe him.

In The Intuitionist, John Henry Days, and Apex Hides the Hurt, Whitehead’s protagonists share one characteristic: They are indistinct. They may barely have names. They are quiet. They are African-American but, as it were, vaguely, as if it’s something to remember, a paradox too deep to even begin to plumb, though they do. They’re hard to fix; the reader has to flesh them out, work to see them, create them along with their author. Here, with a ready-made self, with name and ethnicity brandished like a fake ID from the start, the veil of secrecy behind which Whitehead has done his work is gone, and while this time his protagonist—“That kid,” he says at summer’s end, “who was you and me”—has no trouble talking, he has nothing to say. That’s OK; teenagers have enough problems. It’s not up to them to save the world or give readers lines and images they can’t get out of their heads. That’s a novelist’s business, and no doubt Colson Whitehead will be back at it soon enough.

Greil Marcus is a contributing editor of Artforum. A New Literary History of America, which he coedited with Werner Sollors, will be published by Harvard in the fall.