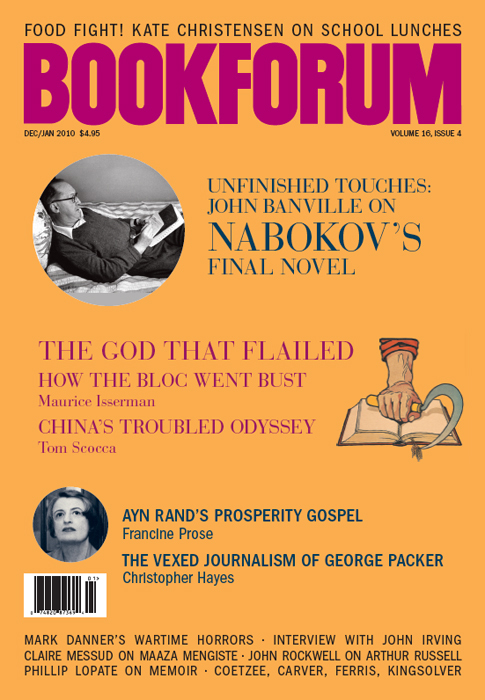

Aptly, we may begin with the title. The dust jacket has it as The Original of Laura: A novel in fragments, while the title page varies this to The Original of Laura (Dying Is Fun). However, the author himself, at the top of the first of the 138 file cards on which the novel—let us call it a novel, for now—is composed, calls the book merely The Original of Laura. The subtitle A novel in fragments is easily accepted as an editor’s addendum, since the book is published posthumously, but where did (Dying Is Fun) come from? Nabokov biographer Brian Boyd tells us that The Original of Laura: Dying Is Fun was “a first tentative title” that Nabokov noted in his diary in December 1974, three years before his death. Dying Is Fun has an appropriately jaunty, Nabokovian ring to it, but did the author himself, or his son, decide that it should be part of the finished title? The book comes to us out of a nebulous region, and any clear glimpse through the mist would be welcome.

That Nabokov left behind an incomplete novel has been known since his death in a Swiss hospital in 1977; known, too, his instruction to his wife, Véra Nabokov—that if he died before finishing the book the draft was to be destroyed. His directive was disobeyed, as such directives frequently are—one thinks of Virgil and the Aeneid and, of course, of Kafka and Max Brod. The latter precedent is specifically evoked by Dmitri Nabokov in his introduction to The Original of Laura. Brod, according to Nabokov fils, never had any intention of destroying Kafka’s work, and Kafka knew it; Vladimir Nabokov “exercised similar reasoning when he assigned Laura’s annihilation to my mother.” Véra’s failure to carry out the grim task was, according to her son, “rooted in procrastination—procrastination due to age, weakness, and immeasurable love.” This is not the first of her husband’s novels to survive thanks to her. In his 1956 afterword to Lolita, its author recounts how on more than one occasion he had carried an unfinished draft to the incinerator but “was stopped by the thought that the ghost of the destroyed book would haunt my files for the rest of my life.” It had to wait for later biographers to point out that it was not the fear of ghosts alone that stayed Nabokov’s hand but the intervention of his wife, who would not allow him to burn the manuscript. Writers’ wives are like that.

For all that, though, the inevitable question arises: If Nabokov said he wanted the draft of The Original of Laura destroyed, and in this instance his wife would not have moved to save the thing, why now, thirty-two years later, has their son decided to publish and risk being damned?

It is not a nice thing to have to say in the circumstances, but Dmitri Nabokov’s introduction is a lamentable performance, stridently defensive, slippery on particulars, and frequently repellent in tone. Aping Nabokov père at his aristocratically disdainful worst, he makes jibes at “half-literate journalists,” dismisses someone’s “asinine electronic biography” of his father, and wearily deplores the “lesser minds” whom it has been his misfortune to encounter over the years when he was debating whether to publish or not. Reading these introductory pages is like being trapped in an airless room with a priggish adolescent dressed up in his father’s outsize clothes—tails, white tie, spats, and all—who expatiates on the awfulness of the masters at his school while puffing on one of Daddy’s finest cigars and turning slowly green.

As to the justifications he offers for publishing the book, it is worth allowing him a good long piece of rope:

I have said and written more than once that, to me, my parents, in a sense, had never died but lived on, looking over my shoulder in a kind of virtual limbo, available to offer a thought or counsel to assist me with a vital decision, whether a crucial mot juste or a more mundane concern. I did not need to borrow my “ton bon” (thus deliberately garbled) from the titles of fashionable morons but had it from the source. If it pleases an adventurous commentator to liken the case to mystical phenomena, so be it. I decided at this juncture that, in putative retrospect, Nabokov would not have wanted me to become his Person from Porlock or allow little Juanita Dark—for that was the name of an early Lolita, destined for cremation—to burn like a latter-day Jeanne d’Arc.

Over the page, and in conclusion, he abruptly drops the lordly manner and says he decided to publish the book because “I am a nice guy, and having noticed that people the world over find themselves on a first-name basis with me as they empathize with ‘Dmitri’s dilemma,’ I felt it would be kind to alleviate their sufferings.” Let us give him the benefit of the doubt.

Ever since word got out that publication of the book was being seriously contemplated, opinions have been canvassed on the matter and have differed widely. Aside from the ethical question of whether the express wish of a dying man should be accepted or ignored, it seemed, to some of us at least, that the sole criterion was whether the novel was in a state close enough to completion to justify its being published. Nabokov was a famously meticulous stylist—none more so, surely, among his contemporaries—and would have died before he would have let work appear that had not been polished to the highest finish. Well, he did die, and the work has been published. Polished it is not, fragmented it is. What we have, in fact, is little more than a blurred outline, a preliminary shiver of a novel. And yet.

This edition is a triumph of the book maker’s art, and the design, by the Nabokovianly named Chip Kidd, is masterly. There will be those who will deplore the production as gimmicky, but the greatest magicians depend on gimmicks for their most elegant illusions. And Knopf’s The Original of Laura is magic right through, from the dust jacket, in sideways-fading white on black with just the merest flicks of gules, past the cloth cover that reproduces the last words of Nabokov the novelist, to the heavy gray pages divided between, on the top half, photographic reproductions of the 138 file cards, front and back, and, on the bottom half, the text in print, including misspellings, slips of the pen, blank spaces, all.

A quibble, or perhaps more than a quibble. The reproductions of the file cards are perforated around the edges, so that, as a “Note on the Text” informs us, they “can be removed and rearranged, as the author likely did when he was writing the novel.” This seems dubious, for the reason that most of the cards have run-over text, and to take them out of the pages and shuffle them would make nonsense of the plot, slight and elusive though it is. And what reader would be so wanton as to remove the very vitals of the book and leave a rectangular hole running through from page 1 to page 275? There will be disputes, dear me, yes, there will be hot disputes.

And the fiction? It is a flux; even the names of the characters are not fixed. The protagonist, if we may call her that, the eponymous original herself, is Flora Wild née Lind, the daughter of a famous and, it would seem, homosexual photographer, and a faded Russian ballerina. The period is hard to pin down, but the milieu seems to be that of the novels Nabokov wrote in his European exile and of short stories from the time such as the masterpiece “Spring in Fialta”: interwar and international, brittle, debonair and dazzlingly superficial. One realizes again what an artistic blessing in disguise it was that the exigencies of the times forced Nabokov relentlessly westward, for America was the biggest and best gift a writer such as he could have received, given his inclination toward mere cleverness and the dandyism of the boulevard. In the great works of his American years, especially Lolita, with its unrelenting background buzz of anguish, we put up with the tedium of wrestling with his puns and his puzzles because we see in them the desperate diversions—yes, the alliteration is catchingof a narrator writhing in spiritual pain. Nabokov’s return to Europe after the great success of Lolita and Pale Fire (1962) saw a falling off, or at least a falling back into the bad old prewar ways. Like Transparent Things (1972)and Look at the Harlequins! (1974)—oh, that exclamation mark!—The Original of Laura is altogether too knowing for its own good, and the tone grates on the ear and the nerves, so that one feels that one has been buttonholed by a relentlessly garrulous flaneur.

Still, the book is deeply interesting, not so much for what it thinks itself to be as for what we know it is: a master’s final work. The flickering narrative of Flora—there are many teasing allusions to Lolita, including a character called Hubert H. Hubert—and her pathetically corpulent but brilliant and rich husband, her anonymous lover who is our occasional first-person narrator, her shadowy friends and the unfriendly shadows through which she moves, gives way gradually to the account of a fat man (it seems to be Flora’s husband, Philip Wild) conducting a thought experiment on himself that, if he has his way, will end in his erasing himself from life, starting with his toes and working upward. It is a nice conceit, and desperately sad, especially as Dmitri Nabokov has informed us of the agonies his father suffered in his final months from inflammation of the toenails. It is a piece of information we could probably have done without. As the son’s account of the father’s last days attests, and as the father’s final novel shows, in contradiction of VN’s subtitle, dying is most definitely not fun.

John Banville’s novel The Infinities will be published by Knopf in February.