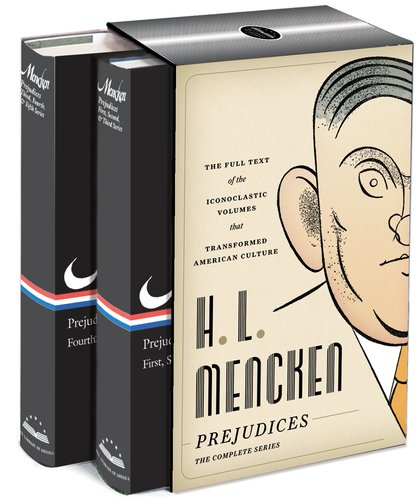

What do you call a revival that never ends? Over the past two decades, publishers have added three biographies of H. L. Mencken—Mencken: A Life by Fred Hobson, The Skeptic: A Life of H. L. Mencken by Terry Teachout, and Mencken: The American Iconoclast by Marion Elizabeth Rodgers—to the three or four that had already been released. Over that same period, Mencken, who died in 1956 at the age of seventy-five, has been more prolific than many living authors. We’ve seen the release of a volume of memoirs (My Life as Author and Editor), a journal Mencken kept between 1930 and 1948 (The Diary of H. L. Mencken), and an anthology that he culled personally (A Second Mencken Chrestomathy). To those, you can add the recently published Mencken on Mencken, made up of autobiographical works not previously anthologized, and A Religious Orgy in Tennessee, comprising his newspaper and magazine reporting from the 1925 Scopes Monkey Trial. And that’s all to say nothing of the steady traffic in reprints of his books on Nietzsche, women, the gods, democracy, politics, literature, and the American language. Now, into this running stream of Menckeniana flows the great torrent of the Library of America’s 1,408-page, four-hundred-thousand-word, two-volume edition of Mencken’s Prejudices series, originally published in six installments between 1919 and 1927.

The Mencken revival has proved so durable largely because its subject planned it that way. Mencken—who worked as a reporter, theater-fiction-music critic, newspaper columnist, magazine editor, memoirist, and linguist—catalogued and stockpiled his unpublished and uncollected writing in a conscious effort to assist future editors and biographers in the exploitation of his back pages. He also instructed his estate to stagger these papers like timed charges, dropping them in 1971, 1981, and 1991. These bursts kept biographers and anthologists busy and focused anticipation on the next blast from the archives. What’s more, all this publishing activity has kept Mencken’s name in the news and very much alive in book reviews. My Life as Author and Editor (1993), which revealed the casual anti-Semitism and racism in Mencken’s private papers, added to his notoriety and reignited the debates over his legacy.

Still, none of this canny posthumous marketing would have borne fruit if Mencken’s legacy weren’t worth preserving in the first place. In many ways America’s poster boy for the modernist revolt against Victorian culture, Mencken wrote raucous prose that remains as contemporary and as controversial as anything printed today. This joyful libertarian had but one operating principle, put succinctly in “The Iconoclast,” published in Prejudices: Fourth Series. “The liberation of the human mind,” he writes, has always “been furthered by gay fellows who heaved dead cats into sanctuaries and then went roistering down the highways of the world, proving to all men that doubt, after all, was safe—that the god in the sanctuary was finite in his power, and hence a fraud.”

Consisting primarily of reviews, essays, and columns produced for newspapers and magazines, the Prejudices series showcases Mencken as polymath and superb rewrite man. As Teachout puts it in The Skeptic, Mencken was the master of the “meticulous serial revision,” in which he would resculpt a Smart Set article or Baltimore Evening Sun column into something more profound, more biting, and more wicked. In some cases, Mencken would retool his best Prejudices pieces one more time for his first Chrestomathy anthology, published in 1949, a process that Teachout calls “a deliberate act of literary and intellectual self-definition.”

This constant reworking of his published pieces exposes Mencken as his own greatest influence. Take, for example, his famous demolition of the American South, “The Sahara of the Bozart,” which began as a modest seventeen-hundred-word piece for the November 13, 1917, New York Evening Mail. Sent through Mencken’s typewriter a second time for 1920’s Prejudices: Second Series, the essay swelled to forty-seven hundred words, becoming ever more Menckenesque. He pummels the former Confederacy, punishing it for its racism, sterility, barbarism, low appreciation of art and culture, and “lack of all civilized gesture and aspiration.” “There are single acres in Europe that house more first-rate men than all the states south of the Potomac,” he writes.

Mencken’s famous hostility to religion knew no bounds. He coined the phrase “Bible Belt” to describe the arc of southern America suffocated by Christianity. (Christopher Hitchens cites Mencken as an important influence in 2009’s God Is Not Great.) Mencken blamed much of the South’s backwardness on its Baptists and Methodists, whose religious excesses, he believed, had arrested their cultural advancement. When he reprinted “Bozart” in 1949, he credited the essay with having helped rejuvenate the backwaters of southern letters in the mid-1920s.

With secular intellectual culture now firmly established, it can be hard to recall just how brave Mencken’s hostility to faith was in the dark days of the early twentieth century. Indeed, this courage infuses many of these pages. In the Third Series, Mencken reduces theism to its essence with this passage:

To sum up:

1. The cosmos is a gigantic fly-wheel making 10,000 revolutions a minute.

2. Man is a sick fly taking a dizzy ride on it.

3. Religion is the theory that the wheel was designed and set spinning to give him the ride.

He was lucky that the Christian mullahs of the Bozart hadn’t lynched him.

While reporting on the Scopes Monkey Trial in Dayton, Tennessee, Mencken observed the local species of Christian up close for a newspaper story, rewritten and collected in Prejudices: Fifth Series under the headline “The Hills of Zion.” Relying on techniques that smack of New Journalism, he and his party creep up on a congregation as they conduct an outdoors evening worship near town. The hymns and speaking in tongues repulse Mencken. “The light now grew larger and we could begin to make out what was going on,” he writes. “We went ahead on all fours, like snakes in the grass. . . . A comic scene? Somehow, no,” he deadpans. “The poor half-wits were too horribly in earnest. It was like peeping through a knothole at the writhings of a people in pain.”

While Mencken’s acerbic views on religion remain fresh, his deep readings of literature have not aged well. For instance, there’s a case to be made against George Bernard Shaw, as Mencken attempts in “The Ulster Polonius” in the First Series—but the playwright’s signal failing is not that “he practices with great zest and skill the fine art of exhibiting the obvious,” as Mencken puts it. This is literary demagoguery.

Likewise, who but an academic remembers the literary criticism of James Huneker, a Mencken favorite in the Prejudices? Who still esteems the fiction of James Branch Cabell? Yet Mencken drops Cabell’s name admiringly in multiple Prejudices essays, going so far as to rank him with Flaubert, Zola, Dreiser, and Rabelais. Should we fault Mencken’s literary judgment because he praised Huneker and elevated Cabell? Or should we cut him some slack because he championed Poe, Twain, Melville, Conrad, Dreiser, and Whitman before they were accepted into the canon? Given that Mencken wrote a pamphlet extolling Cabell in 1927, I believe we can safely demote his lit crit to the second tier.

Mencken devotes most of the First Series to literature before ballooning into an all-knowing, cynical pundit in the Second Series. There, he beats up the prohibitionists, abuses Teddy Roosevelt, damns the censors, and lampoons love as a glandular thing. The Third Series leans toward politics and society, with Mencken calling socialism “the degenerate capitalism of bankrupt capitalists.” The Third Series’s irreplaceable opening essay, “On Being an American,” runs thirty-three pages in this edition and displays Mencken’s good-natured contempt for democracy, the masses, politicians, Bible thumpers, and other conformists. “The American people, taking one with another, constitute the most timorous, sniveling, poltroonish, ignominious mob of serfs and goose-steppers ever gathered under one flag in Christendom since the end of the Middle Ages, and . . . they grow more timorous, more sniveling, more poltroonish, more ignominious every day,” he growls.

The Fourth Series occupies itself with government, the American mind, Comstockery, and the atrocity that was the Volstead Act, while the Fifth and Sixth Series touch all of the stations—politics, religion, society, literature, America, food, sex, eugenics, chiropractors, Puritanism, and the movies. In “Appendix from Moronia,” the last essay in the last book of Prejudices, Mencken aims his wrecking ball at the cinema. It is Mencken at his best and worst. He published it in Photoplay in 1927 after his summer-of-’26 tour of Hollywood, made just before the talkies took hold. Although Mencken tosses off one-liners like a metronome and his language delights the ear, at the age of forty-six he’s become a fogey. He complains that when he first started watching movies thirty years earlier, a whole scene would play out continuously, without cuts. But now shots rarely last more than “six or seven seconds,” and the “result is confusion horribly confounded.” The actors have no talent, he complains. Cinema has no Shakespeare. Mencken sounds like your grandfather bellyaching about the noise and violence of video games.

If many of the pieces in Prejudices start to read the same, there’s a reason. In a 1920 letter to a friend, Mencken explained the simple “formula” of the Prejudice books: “[A] fundamental structure of serious argument, with enough personal abuse to engage the general, and one or two Rabelaisian touches.” Mencken is being a little hard on himself. Nobody produces millions of words, as he did, without leaning on formulas and without revisiting old passions. So don’t approach the Prejudices as if they’re temples of literature. Think of them as Mencken “annuals,” designed for a reading public that wanted to follow his wide interests but couldn’t afford a subscription to a clipping service, and you’ll be well prepared.

Too much Mencken in one sitting can be a very bad thing, either putting the reader off or—worse still—turning him into a mini-Mencken, filled with invective and empty of insight. Mencken beginners would be better off scoring a used copy of the still-in-print selection from the Prejudices that novelist James T. Farrell picked back in 1958. If you’ve already claimed your Library of America edition, the Q&A with its editor, Marion Elizabeth Rodgers, on the publisher’s website will provide a great road map to its best destinations.

Like other Library of America reprints, Prejudices comes entombed in black dust jackets with no explanatory introduction or essay to help the new or casual reader navigate the vastness assembled. The notes and Mencken chronology at the end of each volume, expertly provided by Rodgers, provide only the most basic orientation. Perhaps this plain-wrap approach to publishing explains why so many Library of America editions—especially the ones given as gifts—remain unread or languish in rows at used-book shops like ribbons of funeral bunting.

Don’t get me wrong. Mencken completists—myself very much among them—are celebrating the return of all six Prejudices to print by a publisher that will likely keep them there. But sometimes scarcity trumps a surfeit—as Mencken himself believed. In the Sixth Series, he writes that Ambrose Bierce, a writer he hugely favored, “did a serious disservice to himself when he put those twelve volumes [of his collected works] together.” By Mencken’s reckoning, nobody but a fanatic had ever cracked all twelve, and Bierce should have boiled his anthology down to four or six volumes, maybe even fewer. There was a problem with too much Bierce, Mencken writes: “The result was a depressing assemblage of worn-out and fly-blown stuff, much of it quite unreadable. . . . [H]is good work is lost in a morass of bad and indifferent work . . . filled with epigrams against frauds long dead and forgotten, and echoes of old and puerile newspaper controversies.”

The adult Mencken never composed a worn-out, fly-blown, or unreadable paragraph in his life, but the caution stands: Forage through these pages whenever you’re in the mood, but make sure to stop while you’re still hungry. It will help keep the revival going.

Jack Shafer writes about the press for Slate.