Dear Bob Dylan,

I hope this finds you well. You don’t know me. My name is Rhett Miller. I make albums as a solo artist and as the front man for a band called Old 97’s. I am like you, at least in that I’ve dedicated my postadolescent life to writing songs and singing them for folks. I write you now to pay my respects (much as you did to one of your heroes all those years ago in “Song to Woody”), to thank you for giving so much of yourself, and to ask you: What are we to do now? Here, at this late date, at the tip-top of the Tower of Babel, with all these voices shouting and so few listening, what are we to do?

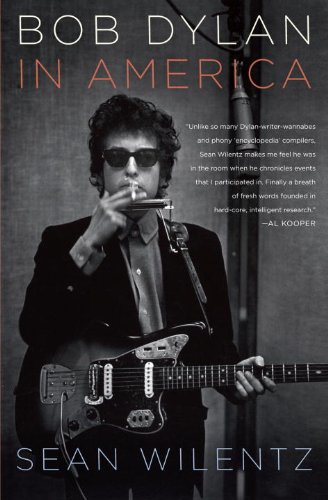

You’re on my mind because I just finished reading a book about you. Its title, Bob Dylan in America (Doubleday, $29), pretty well captures its intent, which is to put you in context and analyze the America around you in the prism of, well, you. I imagine lots of writers have published books about you over the years. I haven’t read them—I’m not a musicologist. I just like listening to and making music. Do you read books about yourself? I’m guessing that you don’t. I bet you’d like this one all right. There’s a bunch of stuff in here that’s not even about you.

The author, Sean Wilentz, is a history professor at Princeton University. That should tell you something right off the bat. He is a fan, but a supremely educated fan. He even places himself on the outer perimeter of your orbit, by pointing out that in 1963, your first meeting with Allen Ginsberg took place in Wilentz’s uncle’s apartment. So there you go.

Wilentz approaches this history of you and your America in a casual way. He was there, you see: at the Philharmonic Hall on Halloween of 1964, at the Rolling Thunder Revue gig in New Haven in 1975, at the Newport Folk Festival in 2002. As he writes, these were all significant moments in your career. He remembers them well. In fact, the accounts of these performances stand out as some of the best parts of the book. He was thirteen, for instance, when he attended the Philharmonic gig, and all these years later, he can still conjure the giddiness of the moment:

Two hours later, we would leave the premises and head back underground to the IRT, exhilarated, entertained, and ratified in our self-assured enlightenment, but also confused about the snatches of lines we’d gleaned from the strange new songs. What was that weird lullaby in D minor? What in God’s name is a perfumed gull (or did he sing “curfewed gal”)? Had Dylan really written a ballad based on Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon?

But Bob Dylan in America also dwells on the “America” side of things. Wilentz, who normally writes political history, fills the background of his portrait with detailed information about the wider cultural and political currents of twentieth-century America that shaped your career.

Part 1 deals with the Popular Front, Aaron Copland, the Communist Party in America, the Beat poets (especially Ginsberg), and the folksingers who preceded you. We’re talking sixty-seven pages of American history from 1934 to 1964. Some interesting stuff in there, to be sure, but I felt a little bit like I was auditing a seminar.

Part 2 is where the narrative becomes just that. The story starts, and it’s a good one. Wilentz builds you much like a character in a novel, using your lyrics to imagine glimpses into your thoughts and motivations. “But the point,” he muses while listening to you sing the final verse of “Gates of Eden” at that Philharmonic gig, “is that outside of paradise, interpretation is futile. Don’t try to figure out what the song, or what any work of art, ‘really’ means; the meaning is in the imagery itself; attempting to define it is to succumb to the illusion that truth can be reached through human logic.” It’s at these moments that I like this Professor Wilentz the most. He gets it—the mystery of experience, the autonomy of real creative work, the pain of constantly being observed and dissected—in a way most people don’t.

And for my money, Mr. Dylan, that’s the gift you gave modern songwriting: You made it into art; you demanded it be treated as art. The book reaches its peak during the chapter chronicling the making of Blonde on Blonde. How great is it that Kris Kristofferson was a janitor in the Nashville studio where you were cutting rock’s first and perhaps greatest double album? Kristofferson points to a moment that could be a photograph of the birth of modern, intelligent rock ’n’ roll: “I saw Dylan sitting out in the studio at the piano, writing all night long by himself. Dark glasses on.” Something magic happened on that record.

Maybe Wilentz gets it right in his analysis: “The lyric manuscripts from the Nashville sessions show Dylan working in a 1960’s mode of what T. S. Eliot had called, regretfully, the dissociation of sensibility—cutting off discursive thought or wit from poetic value, substituting emotion for coherence.” The book shines in these moments, as Wilentz muses on the “possibilities of rock and roll.” As he follows you through the creative explosion that you lived through in the mid- to late 1960s, the book is a pleasure to read, truly inspiring to a guy like me, fighting cynicism and soul-weariness in this strange, barren, posteverything musical landscape.

Unfortunately, that kind of exhilaration subsides as the book nears its conclusion. Its later sections bog down in history, some of it relevant, but much of it downright boring. An entire chapter is devoted to Blind Willie McTell, whom you memorialized in that song you recorded for Infidels but didn’t release until one of those authorized Bootleg Series boxed sets. In the midst of the lengthy, well-researched biographical discussion of this little-known bluesman, the author admits that your song could have been about any number of folks: “Dylan might have been expected to write a song that honored Muddy Waters, Big Joe Williams, Mance Lipscomb, Robert Johnson, Sleepy John Estes or any other of his obvious and long-acknowledged influences, but choosing McTell seemed a little odd. Perhaps it really was no big deal; perhaps McTell’s name simply fit Dylan’s lyrical needs, in rhyme and meter, better than any of the others.” Really? Then why did I just read twenty pages about the guy?

In fact, you might want to skip the book’s final section altogether. A lot is made of charges that you are a plagiarist. Some of the evidence is pretty damning, if you buy into the concept that art must be pristinely original. I know for a fact that you can be a pretty forgiving guy when it comes to such matters. I, myself, rewrote lyrics to your epic “Desolation Row” and recently received word, through management channels, that you had agreed to let Old 97’s release my updated version, called “Champaign, Illinois,” on our upcoming album. Holy shit. Thank you, sir.

You are a hero, not simply for making great art but for persisting amid the soul-crushing forces of this world. And the best moments in Bob Dylan in America show how that persistence gave us a new kind of songwriting and also, into the bargain, your own living, breathing self-portrait that miraculously exists in time, showing all aspiring artists how our struggles can be redeemed in our work. And perhaps that’s the answer to my earlier question. What are we to do now? Just keep doing the work.

I wish you the best.

yrs,