In the final days of the Soviet Union, when the old icons were fast decaying and any future ones were frantically packing off to escape the ruins, the guardians of Russia’s past had few relics to showcase. One of the last heroes standing, a Stalin Prize winner and two-time Hero of Socialist Labor, was Mikhail Kalashnikov, designer of the world’s most famous automatic rifle, the AK-47. Even after the USSR fell, Kalashnikov—now ninety—has enjoyed an afterlife as a living monument to the days when the Kremlin’s fiat reached from Eastern Europe to Southeast Asia and well into Africa. With characteristic bluster, Boris Yeltsin, the would-be revolutionary who overturned the ancien régime, not only crowned Kalashnikov a lieutenant general but draped the Order of Saint Andrew the First-Called—a revived imperial medal—around his neck.

Indeed, as the old order faded, Kalashnikov’s legend only grew, his name becoming a trademark—there would be Kalashnikov T-shirts, Kalashnikov vodka (sold in AK-shaped bottles), a Kalashnikov museum, even a bronze bust in his native village. Russians demanded the myth of a proletarian defender of the motherland. The weapons designer, with his diffident manner, love of Tchaikovsky, and rainbow of medals across his chest, stood nearly alone. Above all, the Russian state needed him. The father of the AK-47 and its long list of progeny embodied the best of a world torn asunder.

The story of Kalashnikov’s unlikely career has been told before. Indeed, he himself has written or cowritten a shelf of autobiographies. These tales, like the flood of interviews that accompanied his coming out in the years of the Soviet Union’s collapse, are suspect. With each iteration, dates shift and names and events remain omitted.

C. J. Chivers is well aware of the murk. He recognizes, moreover, the trouble in digging into the history of the USSR’s best-known weapon. “Little in any independent inquiry into the evolution of automatic arms,” he writes, “can compare in degree of difficulty to an inquiry into the origins of Kalashnikov’s AK-47.” Secrecy, bureaucracy, and lies conspire to defeat researchers. So does the power of proletarian lore. “The Soviet mythmaking mill produced simplified distillations and outright false official accounts,” he notes. “Inventions, handy fables, and propaganda wormed away at the story for decades, institutionalizing falsehoods and calcifying legends.”

The Gun is unlikely to become a Hollywood film (the lead is an aged Soviet arms maker) or a History Channel special (the story spans continents of blood). But it could end up as an opera. In his hunger to chronicle the evolution of automatic riflery, Chivers has written more than one book. The Gun is a wonderful but misleading title. Rather than the story of one man and his gun, there may be three, even four books here. Chivers winds stories around stories, filling his stage with a dizzying cast of characters. Save for a brief prologue, we get to the USSR only on page 140. Instead, the opera opens with introductory chapters on precursors—most notably, the continuous-firing weaponry invented by Richard J. Gatling during the US Civil War and by Hiram Maxim at the height of British colonialism.

When Chivers comes to Kalashnikov’s biography, his tale takes flight. Here is the unlikely rise of a Siberian son, born in the Altai region north of the Kazakh steppe in 1919, the tenth of eighteen children of Cossack peasants deported from their village under Stalin in 1929. His familial home was razed, but Kalashnikov still came of age in that all-too-Soviet fashion: adoring the dictator. The story of his childhood is the Soviet equivalent of a log-cabin tale. Born poor and small, Kalashnikov was “prone to illness.” At five, smallpox hit, and by six, he was so sick “his parents had a casket assembled for him.” We learn much more: Kalashnikov took a liking to poetry and, at age ten, “experienced his first heartbreak,” when his “childhood crush, Zina,” vanished from school. Her parents had been denounced, then deported in the night.

The Great Patriotic War, as Russians call World War II, changed everything. Kalashnikov served as a tank mechanic. In the fall of 1941, after the Nazi invasion, he was wounded at Bryansk. In the hospital, the twenty-two-year-old sergeant fixated on the German advantage: The Nazis, he and his comrades had learned the bloody way, had automatic weapons. The Soviets had only single-shot rifles. By 1946, he had created a prototype, the AK-46, and a year later, his “baby.”

Chivers goes on to chronicle “the breakout,” the weapon’s global spread. When Stalin died in 1953, complete AK-47s were made only in Izhevsk. “Three years later,” Chivers writes, “with the beginning of Chinese production, the world’s two largest military forces had parallel assembly lines.” By 1958, the blueprint had arrived in North Korea, then Egypt. Soon came “the rolling openings of assault-rifle assembly lines in the Warsaw Pact.” The result: “The Kremlin had ensured production of the Kalashnikov at a scale no other firearm had ever seen.”

To what end? The Kalashnikov, as Chivers follows the trail, was christened with blood not as a tool for liberation or to defend the Soviet Union from invaders.” “It made its debut smashing freedom movements. It was repression’s chosen gun.” And in time, as it slipped from state control, AKs would assume new uses—and ascend to new heights of infamy.

Chivers is uniquely positioned to track the twists and turns of this symbolic weapon—and insistently dogs its development. A veteran of Desert Storm and six years in the marines, Chivers was one of the few battle-ready reporters in the United States after 9/11. In his published accounts since, from Iraq, Afghanistan, and Chechnya, he has shown himself to be in the top rank of war correspondents writing in English.

Chivers revels in an obsessive love of fact. He knows well the distance between a report and a rumor; more often than not, he will record the gap. No fact is too small. In the village of Pripyat, in the irradiated zone of Chernobyl, he writes down the name of the referee—I. D. Peshko—who clocked a class of tenth graders as they assembled their AKs (a standard Soviet practice), two weeks before the reactor blew. He also reproduces their scores: “Sergey Salih was the best of all, completing the task in twenty-two seconds; his hands must have been a blur.”

Yet much about Kalashnikov’s role in inventing the AK-47 remains unknown. Given the omnipotence and inertia of Soviet planning, one might presume the bureaucracy would have stymied initiative and innovation. In this scenario, Kalashnikov would have been less central to the weapon’s development. Chivers here does the right thing: Rather than hide the uncertainty, he highlights it. And he explains, as best one can, the reasons for it: secrecy associated with weapon manufacturing, the inaccuracy of Kalashnikov’s memoirs, and the hunger for Soviet John Henrys.

And what role, if any, did Hugo Schmeisser play in the invention? Chivers notes that Russian researchers have learned that the Nazi weapon designer was in Izhevsk after WWII. “Captured by the Red Army after Nazi Germany’s defeat, [Schmeisser] worked at the same arms-manufacturing complex where the AK-47 was first mass produced and then modified.” Coincidence? Hard to imagine. But after restating this fact, Chivers is left to write, more than fifty pages later, that Schmeisser’s “contributions, if any, remain a historical question mark.”

The unrelenting reporting can work at times against the broader logic of the narrative. Chivers marshals his evidence, proffering the earliest instances of a Kalashnikov appearing in a terror act (Munich, 1972), a freedom fight (Hungary, 1956), and a cold-war domino state (Vietnam, via Chinese knockoff plants, “late 1964”). With precision, he details these and other chapters in the “evolution” of the gun. He subjects each case to a high level of critical scrutiny. One is the story of József Tibor Fejes, the twenty-two-year-old whose portrait appeared in Life and who gained fame as the Soviet bloc’s first freedom fighter. Fejes, Chivers writes, had slung an AK-47 over his shoulder, “assumed the requisite pose[,] and begun to flesh out” the “historical role” of the AK-47-toting rebel with a cause—this before Amin, Castro, Arafat, and bin Laden. The hunger for detail builds a nuanced history, based on court records and other sources, of Fejes’s alleged act—the “curbside execution,” as Chivers calls it, of a Hungarian state security officer. But in the end, after raising questions about Fejes’s culpability, he leaves us to wonder how much of a murderer, or rebel, young Fejes really was.

At its best, The Gun brings Chivers’s military experience and analytic mind to the fore. During key passages, the tone shifts, the narrative takes on a cold sobriety, and a new voice, confident and knowing, steals the scene. “Little attracts more attention among armies,” he writes, after depicting the rise of an East German AK-47 plant, “than word that another military force has a new weapon and is investing heavily in its production. Whispers about new weapons can be an emotionally and intellectually powerful variety of intelligence; they inspire curiosity and often worry.” In detailing the torment—at the wrong ends of AK-47s—of a marine platoon in Vietnam, he opens a window onto his own past: “There are moments in modern firefights when combat can become, in an instant, a lonely and isolating experience.” In passages like these, all too infrequent, the narrative turns from the story of a gun and becomes Chivers’s own.

And when Chivers takes readers inside the gun, to explain its unique operation, the writing is windowpane clear: “The release of energy liberates the bullet from the crimp”—the watertight encasement for ammunition in the AK-47—

in a manner reminiscent of the way a champagne cork flies from a bottle. The bullet has nowhere to go but down . . . the muzzle, pushed by expanding gases. As the bullet moves it picks up spin imparted by grooves in the barrel, known as rifling, that force the bullet to rotate on its central axis. The spin will stabilize the bullet in flight, reducing drift and allowing it to travel truer to the shooter’s aim. As the bullet leaves the barrel the excess energy that put it to flight is manifested in several ways—recoil, muzzle flash, noise, and a rush of gas venting into the air.

Chivers also indulges readers with an account of how US technicians have tried to measure the impact on the other end of the rifle’s report, rewinding the macabre history of American weapons testing. In scenes that bring to mind the photographs of Joel-Peter Witkin, he presents Major Louis A.La Garde, surgeon in the Spanish-American War and one of the more inventive ballisticians, who shot cadavers in a Philadelphia armory in 1893; Captain John Thompson, of the Thompson submachine gun, who joined La Garde in shooting bulls in the Chicago stockyards; at the Colt facility, operatives who tested the AR-15 in 1960 by firing three hundred rounds into a 1951 Pontiac Catalina; General Curtis LeMay, antihero of the Vietnam War, who blasted a pair of watermelons on an arms executive’s farm; and the Pentagon, which resorted to importing “27 severed heads” from India for a 1962 lethality test. And yet for expertise, Chivers tops the experts:

The hips, upper thighs and pelvic girdle are among the worst places for a rifle bullet to smack into a human being. Wounds to these areas are often instantly immobilizing. Load-bearing bones rupture. Victims buckle and collapse. Complicating matters and raising risks of swift death, large blood vessels follow the contours of bones. If cut, these blood vessels tend to bleed heavily and in ways that can be hard to stop. In the mad race to stop the flow, pressure and tourniquets are hard to apply.

Given Chivers’s skills, it’s not surprising that one act of his opera stands out: the nearly hundred-page chapter on the birth of the M-16, America’s miserable counterpart to the AK-47. The story of the bastard birth and rushed introduction of the M-16 into the US Armed Forces on the eve of war in Southeast Asia is not new. But Chivers reports it in the investigative tradition of Seymour Hersh, combined with the precision of John McPhee. These pages are not about the pitting and rust inside the rifle, but the confluence of greed, lies, bloodlust, and—he does not shirk from revealing—a murderous lack of conscience.

The Pentagon’s planners had spotted the Soviets a “fifteen-year head start”—what Chivers calls the “gun gap.” In Vietnam, he writes, American GIs would pay for that lag “in blood.” Chivers follows the Hill Fights of the marines of Hotel Company, First Platoon, “one of the bloodied outfits in Second Battalion, Third Marine Regiment.” His chronicle of the M-16 is satisfying in a way that his tale of the AK-47 cannot be. He has mined the public record and unearthed witnesses alive and dead. He’s interviewed Vietnam veterans, dug up the Pentagon’s paperwork, and confronted Colt’s executives. And he has read the letters from Vietnam of First Lieutenant Michael P. Chervenak—one of the few men of conscience in the book—a marine who broke the code of silence by writing in an open letter, published in the Washington Post, about the M-16’s propensity to jam. He’s also read the letters of Kanemitsu Ito, a Colt engineer who saw on the battlefield the damage done to his company’s gun—and to men who carried it. Chivers has the goods on them all.

In the bravura account of the M-16 saga, we’re reminded that The Gun is nothing less than a history of modern warfare as seen through the narrow scope of automatic riflery. That approach might seem myopic. But consider Chivers’s point: that generations of Western generals and heads of state focused on missiles, aircraft, and nuclear arms, while the AK-47 and its relatives were the clear and present danger. “Rifles were just rifles,” he writes. “Who worried over a weapon with a range of a few hundred meters, which injured its victims bullet by bullet, when a neighboring state was updating its jet fighters, and main battle tanks?” “The American intelligence community would fixate, understandably and properly, on the Soviet Union’s nuclear programs.” And yet Kalashnikovs became “the most lethal instrument of the Cold War.”

Meanwhile, in Russia, the hero worship continues. Last winter, on the gun designer’s ninetieth birthday, President Medvedev awarded Kalashnikov the land’s highest honor, naming him a Hero of Russia. Kalashnikov, Medvedev said, had fathered “a national brand that makes each citizen proud.”

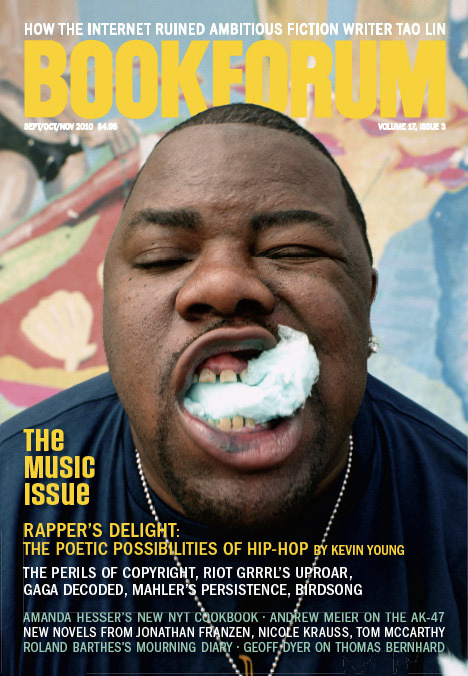

Andrew Meier is the author of The Lost Spy: An American in Stalin’s Secret Service (Norton, 2008). He is currently at work on a biography of Robert M. Morgenthau and his family.