In early February of 1962, poet Ted Berrigan, age twenty-seven and virtually unpublished, drove from New York to New Orleans to visit his friend Dick Gallup, a student at Tulane. (They had met in Oklahoma. The two of them, along with Joe Brainard and Ron Padgett, would eventually be affectionately dubbed, by John Ashbery, the “soi disant Tulsa School” extension of the even more humbly tagged “second-generation New York School.”) Another reason for the drive was that Ted wanted to check to see whether his first, self-published collection, A Lily for My Love (1959), was stored at the Library of Congress, so that, if so, he could steal it to destroy it (juvenilia). It was and he did. A couple of weeks later, he carried out another of the trip’s aims, the acquisition of his master’s degree at the University of Tulsa, thereby enabling his immediate return of the diploma with the explanation that he considered himself “the master of no art.”

Berrigan, though almost always broke, lived large poetically. Hardly anyone was there to notice when he made the above-noted legend-worthy gestures. He was the fully self-aware Quixote of poets: a funky god, the Quixote who was his own author, inventing himself out of what was lying around. The value of human gods is the inspiration they provide. Berrigan’s time on earth (he died in 1983) gave us proof that it’s possible to live full time solely as a poet, suffer all the horrible material consequences of that commitment, and remain (mostly) lovely, largehearted, and sane. This while contributing great beauty and wit to the reservoir of poetry. If only he’d lived longer, been a bit healthier. Do the human gods have to die young? More often than not, it appears. Still, their inspiration is real and important.

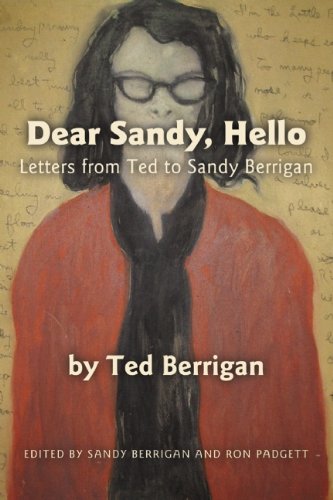

In New Orleans, Gallup introduced Berrigan to nineteen-year-old college student Sandra Alper. Six days later, Ted married her. Within two weeks, Sandy’s parents, who’d lured the newlyweds to visit them in Miami, had her committed to a mental asylum in hopes of getting the marriage annulled. At the behest of Sandy’s father, a prominent physician, the Dade County police pressured Ted to leave town, and he returned to New York. Dear Sandy, Hello collects the letters that Berrigan wrote his bride, almost every day, across the two months before he returned to help her escape from the hospital.

There are a few currents of feeling and information running through the letters. They are love letters foremost, but they also present Ted’s radical poet’s values. He is more than once forced to explain that, however differently Sandy’s father or shrink might portray it, Ted’s choice to scrounge and shoplift and read and write poetry rather than to get a job is a noble one. We get a running account of the books he is reading and the art and movies he is seeing; we see his sensibility developing. Recurring references are made to the quality sabi, a Japanese spiritual/aesthetic concept cherished by Berrigan, which he tries to evoke as “the ‘good old days’ which of course never really existed. . . . October in the ‘Railroad Earth.’ . . . Thomas Wolfe is full of it, and so are old cowboy movies, and even old gangster movies, and poems by Frank O’Hara sometimes. . . . Marcel Proust writes about it a lot, particularly in Swann’s Way.” “October in the ‘Railroad Earth,’” is, of course, a Kerouac reference. Berrigan loved the Beats, but he was equally crazy for the first-generation New York School, especially O’Hara and Ashbery. Those literary circles, one seemingly rooted more in spirituality, the other in cosmopolitan sophistication, are sometimes seen as incompatible; they are synthesized in Ted.

Excitingly, the letters catch Berrigan on the cusp of the breakthrough that would lead to his innovative, influential masterpiece, The Sonnets (1964). It’s a real kick to read him offering Sandy lines from an undistinguished, conventional pre-Sonnets sonnet (“These days I burn, and I can not be still, / Burn I must, for with fire must I kill, / those griefs in me make me hurl my rage / upon those whose griefs I would most assuage”) and find a phrase—“whose griefs I would most assuage”—that, once he arrived at the collaging, phrase-shuffling technique of The Sonnets, would become beautiful and apt in multiple poems of the sequence.

He also refers throughout the letters to his ongoing composition of a loose, personal translation of Rimbaud’s “The Drunken Boat.” In a three-page explication, he calls the poem “a manifesto against my own need to hate those people whom I must not be like.” Berrigan was always consciously struggling to be a good person; in one of the first of these letters, he defends Sandy’s parents to her. (Later we learn in a passing editor’s note that Ted was having an affair in New York with a high school acquaintance of Sandy’s in this same period. Somehow, it doesn’t seem inconsistent.) His analysis of the annexed “Boat” is surprising, but it’s also interesting and even, in context, plausible. While his swashbuckling “imitation” is wonderfully faithful to the substance of the original, he conceives of it as dealing with specific, momentary Ted Berrigan issues. “Boat” lines will positively pervade The Sonnets, too.

Granted, this is probably not the volume from the Berrigan shelf that a reader unacquainted with him should acquire first. That would be his Collected Poems (2007). But for anybody with a taste for Ted, this book is another sweet addition to the happily increasing literature by and on the subject.

Richard Hell’s latest novel is Godlike (Akashic, 2005), and his most recent album is Destiny Street Repaired. He’s currently working on an autobiography.