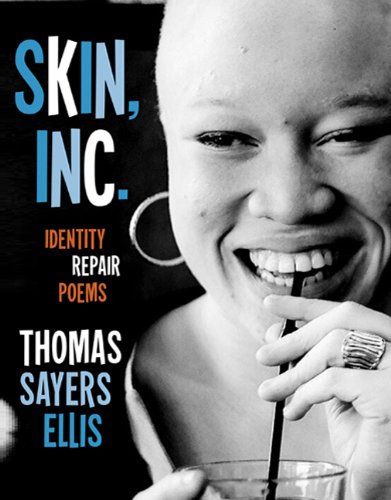

Racial identity and aesthetics may not spell fun to most, and poems about those topics even less so. But a strong sense of play infuses Thomas Sayers Ellis’s Skin, Inc.: Identity Repair Poems. This is a poet who can use the same word eight times in a single stanza without sounding redundant: “coloring color the color / I want to color color, not the color / color colors me.”

These themes do come bearing history—particularly the legacy of the Black Arts Movement. In 1971, in the introduction to the anthology The Black Aesthetic, literary critic Addison Gayle made a case against integrating black culture into that of mainstream America for fear of its usurpation. His argument presumed that fundamental differences between black and mainstream culture existed and needed to be maintained due to the inability of most people, especially white liberals, to see the black experience as broadly American.

To this point, even Ellis’s metaphorical manifestations of whiteness are circumspect. As he writes in the poem “Spike Lee at Harvard”: “As auteur, as author / I pray this last stanza / won’t fade or break / into whiteness, the tense silence.” For some, it may seem surprising that in this time of Obama, there is frustration among writers who see a dwindling interest in work that has not moved past the subjects of culture and color. In “The Judges of Craft,” Ellis cites his own rejection letters from literary journals: One editor dismissed a poem for being “too strident” in its assessment of racism; another felt its way of “addressing . . . the politics of the writing scene” wasn’t novel enough. Such interrogations of the dynamic between the (black) poet and publishers aren’t the rule, but they are powerful enough to set a decidedly political tone for the volume.

The title poem, “Skin, Inc.,” suggests that “a deeper sense of verse frees skin,” and that this freedom is achieved when those identities (often blamed for making a poem too particular and therefore inaccessible) claim authority over the act of representation: “I am not merely in / this thing I am in. I am it.” Inc. signifies the market value of skin, while the letters for in, embedded in both words, invite the question, What position does an outsider desire? The homonym to the book’s title—“skin, ink”—emphasizes the idea that a corporeal connection to a poem is inevitable, a point illustrated by the lines “This lyric body / a prosody, sentenced.” In “The Identity Repairman,” bodies named for type or difference—“African,” “Slave,” “Negro,” “Colored,” “Black,” or “African-American”—become the substance of metaphor as the narratives surrounding their identity reveal epic tensions.

Tracking the rich array of allusions provides great pleasure amid such serious meditations. Drawn from black vernaculars, games, music, literature, and art across the Americas and Africa, these references are shaped into aural and visual patterns in “The Judges of Craft”:

Continuation.

Containment is not permanence.

Confinement is not content.

Culture is home.

The body, its own guest.

Imagination, host.

In his first book, The Maverick Room (2004), Ellis proved a master at intentionally mistelling a familiar lyric or phrase through direct or indirect homophony. Word and typographic play inform content as well, most noticeably in “The Pronoun-Vowel Reparations Song,” which relies on the vernacular pronunciation of long vowel sounds arranged in the style of an eye chart to evoke a call for reparations (both material and spiritual) when sounded out: “A E U O I”—you owe I.

Two of the longest poems in Skin, Inc. are “Mr. Dynamite Splits” and “Gone Pop,” elegies for, respectively, James Brown and Michael Jackson. The former exemplifies what Ellis calls a “perform-a-form,” an alliance between poetry of the stage and poetry of the page. It “occurs when the idea body and the performance body, frustrated by their own segregated aesthetic boundaries, seek to crossroads with one another. This coupling . . . will repair and continue the living word”: “Can I go back to the top / Yeah / Can I start one mo ’gin / Yeah / Can I start like I did be f-o-r-e / Yeah.”

In “Gone Pop,” which constitutes the last quarter of the book, the poet abandons the lyric “I” and its emotional connection with the reader to trace through biographical episodes how Jackson’s identity grew exaggerated beyond the possibility of repair. Changes in Jackson’s skin color due to vitiligo made people study his body for signs that he was still black, to clarify whether he was one of “them” or one of “us”: “We Had Him, he was ours, / all of him—the needle marks, clusters of bruises, and burnt scalp. / Although the lighter his skin got / the more unlike us he got.”

The “us” that forms in response to the loss of Brown and Jackson becomes a community, the “recognizable We, / an I-identifiable many” who might claim space “throughout every alphabet.” To take up that much room, that “We” must have the courage to surpass “genre and ism.” Gayle imagined the work of the black critic to be corrective—“a means of helping Black people out of the polluted mainstream of Americanism”—and a similar goal marks this collection. Because if what is at stake is a people’s survival, as Ellis suggests, there has to be “more to words than becoming books.”

Wendy S. Walters’s book of poems Longer I Wait, More You Love Me was published last year by Palm Press. She teaches at Eugene Lang College in New York.