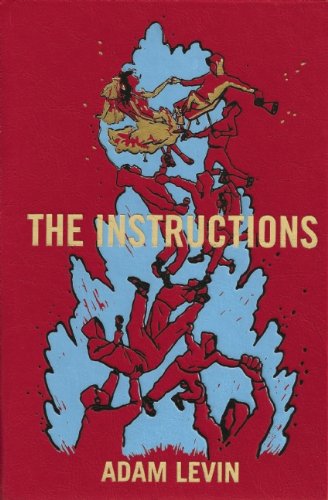

Ambition is an attractive quality in a book, and Adam Levin’s first novel, The Instructions, is Napoleonically ambitious, a 1,030-page brick wrapped within a metafictional conceit. The book is, supposedly, a 2013 edition of a “scripture” by protagonist Gurion ben-Judah Maccabee. The first half has been translated from English into Hebrew and back into English, retaining, due to its “translingual” immutability, its original wording. This is only one of the miracles attributed to this text and to Gurion, who spends the better part of the book steadfastly insisting that he’s not the Jewish Messiah, although he eventually lets on that he wouldn’t mind if he were. Did I mention that Gurion is brilliant, psychotic, deeply charismatic, and ten years old? He is. Also, he’s half-Ethiopian. (“Really?” his girlfriend says. “You don’t look Ethiopian.”) And almost the whole thing takes place over four days in November 2006. Take that, Infinite Jest.

As is often the case with first novels, The Instructions owes some substantial debts to its forefathers: Its DNA includes a little bit of The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao and Saul Bellow and Helen DeWitt’s The Last Samurai, a bit more of Thomas Pynchon (characters are named Ben-Wa Wolf, Ronrico Asparagus, Jelly Rothstein), a bunch of J. D. Salinger’s Seymour Glass stories (especially “Hapworth 16, 1924”), a hell of a lot of David Foster Wallace (whose signature “and but” construction even shows up a few times), and massive quantities of Philip Roth, whose trophy for Great American Jewish Novelist Levin practically tries to wrest away. (Near the book’s climax, Gurion—who shares parts of his name with the first prime minister of Israel and with the hero of the Hanukkah story—tells a reporter that he’ll start killing hostages unless the authorities put him on the phone with Roth.) Levin’s tome addresses all the big themes of Jewish-American fiction—culture within culture, sex, guilt, exceptionalism, self-hatred, assimilation, the Israel problem, what’s “good for the Jews”—but flips most of them upside down and dresses them up in every clever formal device Levin can juggle.

As The Instructions begins, Gurion is almost literally in bondage: Having been kicked out of a series of Jewish day schools, he spends his days in a cage for disorderly students at Aptakisic Junior High (an actual school in a suburb of Chicago), writing long, eloquent essays for his detention assignments, thinking a lot about the Torah, stockpiling small objects he can use as weapons, and establishing an army of fellow outcasts from his present and past schools. Gurion calls himself and his followers Israelites rather than Jews: They’re defined by exile rather than by belief, and their readiness to imagine themselves as put-upon underdogs rapidly mutates into an eagerness to attack any potential target. (In the opening scene, he and a couple of his friends “waterboard” one another in a pool “to learn what it was we feared more: being misunderstood or being betrayed.”)

The story is set in motion when Gurion falls in love, or a ten-year-old’s idea of love, with the very goyische Eliza June Watermark; one thing leads to another, and seventy-five hours later, his legions have launched a violent attack on their oppressors—teachers, jocks, popular kids—during a performance by a Justin Bieber–ish schoolmate known as Boystar, who’s filming a video for his new hit, “Infantalize.” The book’s driving force, though, is less its plot than Gurion’s voice, which is talmudically obsessed with worrying out every possible interpretation of everything, spiked with private argot and personal diction (stealth is both an adjective and a verb here), and pumped up to mock-biblical grandeur (“And there was night, and there was morning, Wednesday”). It can be pretty hilarious, especially if you’re familiar with the language of Jewish culture. This is how Gurion imagines a future holiday based on his exploits:

At the holiday meal, the youngest boy present would ask his father . . . a set of four questions. The boy would say, “Why on this night do we wear handcuffs and leg-shackles at the dinner table?” And his dad would say, “Because our hero and his people, our people, were restricted in their movements by robots and the arrangement.” And the boy would say, “Why on this night do we smash glass bottles on the pavement in the parking lots of our township?” And his dad . . . would say, “The glass bottles are clear like the rules of the robots, and all clear things may be broken and so all clear things should be broken and shall be broken, for the noise of their breaking is the only pleasure to be gotten from them.”

But despite (or perhaps because of) his ambition, Levin falls into a handful of debut-novelist snares. Gurion is a wise-child archetype straight from central casting: There’s always comedy in having hypersophisticated analysis coming from someone with a kid’s blinkered understanding of the world. He’s also nearly the only character in the book who’s more than crudely sketched out, perhaps a side effect of having a totally self-obsessed narrator. Almost every other character shares his distinctive speech patterns to some extent, a problem Levin partly works around by having several characters explain that people who spend time around Gurion tend to start thinking and talking like him.

Levin falters as he tries to cram every formal possibility for the contemporary novel into The Instructions. Beyond its future-double-translation framing device, it incorporates e-mail chains, school papers, an exegesis of Fugees lyrics, editorial commentary, footnotes, typographic tomfoolery, television transcripts, real-life celebrity cameos, maps composed entirely of text, a minor role for a character who shares the author’s last name, commentary on what happens “the first time you finish any truly great book that isn’t the Torah,” and above all else declarations of self-awareness. A forty-nine-page digression on how Gurion’s parents met is not just a story, it’s entitled “Story of Stories,” and it’s presented as the narrator’s fourth-grade creative-writing assignment, preceded by our hero’s note to his teacher explaining that he’s decided to compose scripture rather than fiction:

I want you to know that I’ve put a lot of thought and effort into making this scripture acceptable on all grounds—to make it feel fictiony enough so you know I’m not thumbing my nose at your assignment, but also to let it be as completely true as it is. For example, I’ve written sentences which are unlike those I have used in previous assignments, in that they have a lot of dependent clauses as well as occasional Yiddishe inversions and inflections, so that I sound like a narrator named Gurion ben-Judah, rather than the Gurion ben-Judah you know in real life.

Gurion’s hairsplitting, rambling explanations are enormously entertaining up to a point, but that point is significantly before the page count hits quadruple digits. There is probably a sharp and funny three-hundred-page novel hidden in The Instructions; what’s actually present is delightful for its first few chapters, then dissipates into way too many unkilled darlings, set pieces that lead nowhere, and slo-mo descriptions of ghastly violence that mix with the book’s Catskills shtick like meat and milk. And the ending fizzles: It’s a shaggy-dog punch line that Levin’s been teasing for most of the book, followed by a “coda” in which he effectively shrugs and admits that there’s really no way to resolve most of what he’s set up.

As an advertisement for the rest of Levin’s career, though, the book is irresistible. Its chief flaws are too many ideas, too much enthusiasm, too much intoxication with the glory of its language. (One of its minor characters is “a three-hundred-pound bachelor hoodooman with silvershot dreadlocks and a chrome-knobbed walking cane who’d written four novels he said cast spells”: There’s practically enough for a book right there.) Those are promising problems to have in a first novel, and as maddening as it becomes, The Instructions—with its combination of craft and chutzpah—suggests that Levin’s got some remarkable books ahead of him.

Levin offers a possible clue to what he’s up to when he provides a glimpse of an earlier scripture of Gurion’s: “Ulpan,” a brief set of directions for turning a soda bottle, a balloon, and a penny into a gun, concluding with a directive to pass it along to other Israelite boys. Ulpan, as it happens, is a Hebrew word that means “instruction,” used to refer to the immersion courses that teach new immigrants to Israel the Hebrew language and Israeli culture. The Instructions is an ulpan of its own: an immersion course in the future of the Jewish novel as Levin imagines it. If it doesn’t quite get its readers to the Promised Land, watching it try to part the Red Sea is still pretty impressive.

Douglas Wolk is the author of Reading Comics (Da Capo, 2007) and a 2010 USC Annenberg/Getty Arts Journalism Fellow.