Giacomo Leopardi may be the most erudite, philosophically astute, and linguistically refined poet you’ve never heard of. Part of the blame lies in Leopardi’s historically inclined vocabulary and style, which draw heavily on Greco-Roman authors ranging from Theocritus to Virgil as well as early Italian masters, especially the fourteenth-century Tuscan poet who was the preeminent model for Renaissance lyric, Francis Petrarch. But Leopardi was no antiquarian: His synthesis of past literary forms and experimental poetics makes his work a daunting mix of erudition and inventiveness. It would be an oversimplification to call Leopardi’s language Italian, because, like Italy itself, such a thing did not yet exist in his brief lifetime (1798–1837). Italian unification, and with it the standardization of the national tongue, didn’t occur until the 1860s. He would never see the official Italy whose cause absorbed a great deal of his career.

Leopardi’s nearly “inexhaustible energies,” as Jonathan Galassi describes them in the introduction to his new translation of the Canti, fueled such projects as a massive philosophical notebook called the Zibaldone, a series of operette morali (moral tales) on issues ranging from the necessity of illusion to the nature of literary fame, and seminal essays on Italian Romanticism and the character and customs of the Italians. But it was his poetry that earned Leopardi immortality in Italy—a Janus-faced poetry that presents the translator a grim set of challenges. There are two lyric Leopardis: the nationalist one—inspired by such authors as Vittorio Alfieri and Dante—who composed a series of monumental odes about his fragmented country early in his career; and the more introspective mature author, whose idylls and less declamatory poetic forms sealed his reputation as Petrarch’s modern heir.

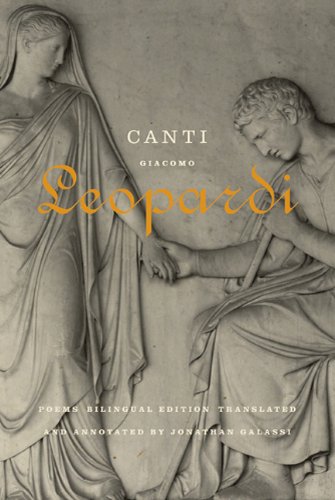

[[img]]

The mere forty-one compositions that make up the Canti, a carefully structured life-in-verse in the tradition of the Petrarchan canzoniere (songbook), contain a dazzling variety of styles and themes, from confessions of private pain and humiliation to philosophical satires and grand pronouncements on current events. Leopardi’s engagement with contemporary Continental philosophy and insatiable interest in international literary culture has helped make the Canti the rare work of Italian poetry to find its share of foreign readers and translators. By detailing the text’s complicated evolution, Galassi underscores Leopardi’s desire that the Canti be read as a “book” and not as a mere collection of songs. The marvelous achievement of Galassi’s translation is most palpable in the odes. The few other English versions of them I’ve encountered over the years either overstate the diction to suggest a grandiosity not in the originals or fail to match the solemnity and dignity of Leopardi’s lexicon and structure. Galassi deftly negotiates this challenge through austere word choices that avoid preciosity and sentences that evoke Leopardi’s cadences without twisting the English into Italianate clauses. For example, in the final lines of “To Angelo Mai,” dedicated to the Vatican librarian who discovered Cicero’s De re publica, a text Leopardi hoped could serve as a blueprint for Italian political freedom, the poet employs the rarefied speech and exhortative mode that define the odes:

arma le spente

Lingue de’ prischi eroi; tanto che in fine

Questo secol di fango o vita agogni

E sorga ad atti illustri, o si vergogni.

Rearm the dead tongues

of our pristine heroes, so at last

this age of mud will either want to live

and rise to noble action, or be shamed.

Galassi captures the martial, classicizing feel of the original (helpfully printed on facing pages) with deft choices like “pristine” for prischi and by resisting the temptation to make fango sound more decorous than the “mud” Leopardi intended. Except for the rare lapse (“exemplars of baseness” for di viltade esempio, which would be less labored as “a base model of cowardice”), Galassi’s odes gallop alongside the originals at an even pace.

Translating the idylls carries yet greater demands. Like Petrarch, Leopardi employed in his more introspective lyrics a highly controlled and sonorous diction and tended to revisit obsessively a few themes. As a result, English versions of these poems can seem repetitive and simplistic, as if the loss of the original Italian has doomed the reader to hearing the message but not the music. Galassi succeeds at a thankless task: conveying the refined, spare elegance of the originals without resorting to a poetic-sounding voice that the Italian never calls for. He shows the same restraint as Leopardi, and by striving for fidelity he shrewdly keeps the English in hearing distance of the Italian. For example, in translating Leopardi’s most celebrated idyll, the youthful “Infinity,” Galassi uses a rhythmic lilt and internal rhyme (“till what I feel / is almost fear. And when I hear”) to match the pacing of the original, which contains the internal rhyme cor / spaura and a pattern of o sounds in ove per poco. In the Italian, the idyll achieves a quiet symphonic flourish through accumulated conjunctions whose flow implies nature’s force; Galassi’s tumbling clauses follow suit:

and the eternal comes to mind,

and the dead seasons, and the present

living one, and how it sounds.

The difficulty of translating Leopardi’s verse is well known. Eamon Grennan, whose well-regarded translation of Leopardi’s Selected Poems (1997) generally takes more dramatic liberties with the original than does Galassi’s, renders the title of the idyll as “Infinitive” and the above lines as “And a notion of eternity floats to mind, / And the dead seasons, and the season / Beating here and now, and the sound of it.” Like Galassi, John Heath-Stubbs in Poems from Leopardi (1946) goes for a more literal version, but his capitalization of “Eternity” gives the poem an unwelcome allegorical feel, and his rendering of suon as “noise” instead of “sound” jars the ear. Thomas Bergin and Anne Paolucci are the closest to Galassi—and to Leopardi—with “and the eternal comes to mind, / and the dead seasons and the present living / one, and the sound of it” (Selected Poems of Giacomo Leopardi [2003]). In this passage as elsewhere, Galassi fulfills the promise of his en face edition by drawing the reader to the Leopardian language that shadows his translations throughout.

Leopardi’s legendary suffering and unhappiness circulate throughout his lyric corpus. Born into an aristocratic family in the backwater town of Recanati, Leopardi has entered Italian lore because of the Mozartean precocity of his childhood and the physical deformity and emotional isolation that followed. Barely a teenager, he had already learned all his tutors could teach him; then came several years of what Leopardi termed “mad and desperate study,” where he devoured the titles in his father’s substantial library and taught himself languages ranging from ancient Greek and Hebrew to modern English, German, and Spanish. These “labored pages / on which my young years / and the best of me were spent” (“To Silvia”) seriously compromised the poet’s frail and sickly constitution: By adulthood, Leopardi had developed nervous disorders, poor eyesight, and a hunchback. The world of endless youthful study serves as the backdrop for the celebrated “To Silvia,” whose conversational first two lines cede (typically) to a stylized rhetoric that seems more about a muse than an actual female:

Silvia, do you remember still

that moment in your mortal life

when beauty shimmered

in your smiling, startled eyes

as, bright and pensive, you arrived

at the threshold of youth?

It is a testament to Galassi—and his co-translator on this one poem, Tim Parks—that the shift from actual to ideal girl, conveyed through subtle transition from the homespun “smiling, startled eyes” to the stately “threshold of youth,” registers in the English. In Italian, the beginning of the poem is deeply intimate, as the m and v sounds coalesce into a hum (“Silvia, rimembri ancora”) that lingers in the subsequent series of imperfect verbs and their equally gentle v’s:

The quiet rooms

and streets outside

echoed [sonavan] with your endless song

as you sat [sedevi], bending to your woman’s work,

happy enough with the hazy

future in your head.

It was fragrant May:

and so you spent [solevi menare] your day.

The Italian imperfect implies repetition, leaving us with the image of an industrious girl always with a song on her lips, just as the informal address make us feel as though we are eavesdropping on a private conversation. But verses later, the reader learns the sad truth about the tenerella (“gentle girl”) Silvia: “You, before winter had withered the grass, / stricken then overcome by hidden sickness, / died.”

Leopardi was not necessarily aware of this poem’s slide from conversation to elegy—and not just because this reclusive poet had little actual contact with women. The reason lies instead in Leopardi’s tendency to abstract human experience according to the parameters of whatever literary genre or mode he happened to be working in. For example, in the ode “To Italy,” Leopardi demands with high Alfierian rhetoric that he be brought his sword and declares that he will “fight alone . . . fall alone” for his country; in the idylls, such assertiveness gives way to melancholy inflected with the concerns of the form at hand (the sonnetlike “To the Moon” alludes to Petrarch and fittingly ends, “how sweet it is remembering what happened, / though it was sad, and though the pain endures!”). Yet his work is anything but formulaic, just as the unrelenting pessimism of his existential insights is hardly depressing. “To Silvia” ostensibly narrates how the tragic early death of a servant’s daughter reminds the poet that “man’s fate” is always ready to stamp out innocent hope. But the energy of the poem moves in an altogether different direction. In those hummed m’s and v’s of the poem’s opening, the tenerella lives on forever, softly and sweetly. Any melancholy or sorrow the poem causes finds its counterpoise in a music and an intelligence that dare to challenge death and cosmic injustice, however inexorable.

Galassi notes in his introduction that Leopardi is Italy’s “first modern poet,” whose experimentalism and philosophical themes culminate in what became a major concern for the following two centuries of Western lyric: “a new self-consciousness of the writer’s alienation from life, with the constant companionship of pain and the consolation of the power of memory—all evoked with unmediated directness and haunting expressive beauty.” I would go further and say that in addition to helping inaugurate lyric modernity, Leopardi is also one of the more prescient and incisive critics of the modern age. It is no coincidence that perhaps the most influential and savage skeptic of modern morality, Friedrich Nietzsche, greatly admired Leopardi. In “To Angelo Mai,” Leopardi muses that his age is one where “mathematics is preferred to song,” an indictment of the utilitarian faith in progress that finds bitter expression in what many (myself included) consider his finest composition, “Broom, or the Flower of the Desert.”

Composed just a year before his premature—and, if we accept Leopardi’s endless petitions for death to rescue him, welcome—demise in 1837, this poem’s late date, intellectual density, and interweaving of trademark motifs give it the feel of a summa of the poet’s career and worldview. The epigraph provides access to the mind and spirit of the Leopardian corpus with a signature message, “And men loved darkness rather than light” (John 3:19), and the poem tells of a plant that has somehow managed to bloom on the slopes of Vesuvius while the ruined city of Pompeii stretches out below. This “scented broom” is no less than an allegory for Leopardi as poet: Each, humbly yet defiantly, “embellish[es] the lonely plain / around the city,” the plant with its fragrance, the poet with his song; each “seems to bear witness.” The broom is yet another of the marginal, star-crossed types that emerge as analogies for Leopardi’s poetic voice in the Canti, a list that includes the long-suffering Greek poetess Sappho, a solitary thrush, the tenerella Silvia, and above all Leopardi’s cherished moon, the presence most often invoked in his verses. In “Broom,” the vocational identification between Leopardi and the plant reaches an unprecedented pitch; both are like voices crying out in the desert:

Now one ruin envelops everything

where you take root, noble flower,

and, as if sharing in the pain of others,

send a waft of sweetest scent

into the sky, consoling the desert.

The link between poetic song and floral scent gives way, as the poem progresses, to darker matter. Never one to mince words or hide his resentment—another reason for Nietzsche’s devotion—Leopardi intones:

Look here and see yourself reflected,

proud and foolish century,

who gave up the way forward

indicated by resurgent thought,

and, having changed course,

boast of turning back

and call it progress.

The critique of modern progress echoes his earlier decrial of “the magnificent, progressive destiny” (Leopardi’s italics) of humankind. Leopardi is not one much given to irony. Yet here, as in the even more cynical “Recantation for Marchese Gino Capponi,” his reflections on the state of the world present him at his most peevish, sarcastic, and apparently unforgiving. “Broom” includes the admission that Leopardi will go to the grave with “disdain” for his age “locked inside my breast.”

The above words from “Broom,” however, represent only one side of Leopardi, the social critic, no doubt a compelling figure but ultimately less engaging than the Leopardi who identifies with the desert flower. In the end, the proud, indeed hubristic contemporary men and women he excoriates in “Broom” are as helpless as ants before an “unholy” and “evergreen” nature, which “with the slightest movement” can destroy the works of humankind as decisively and indifferently as she did Pompeii, “in the horror of the hidden night,” “advancing cruelly through empty buildings / [its deadly lava] like an evil torch.” The poem shows that the human moment stands no chance in the face of cosmic time; thus, the poet’s stated disdain for his fellow humans seems more like a mask covering his wounded pride and implicit solidarity. In the final tally, Leopardi sees his job, like the broom’s, as bearing witness:

And you, too, pliant broom,

adorning this abandoned countryside

with fragrant bushes,

you will soon succumb

to the cruel power of subterranean fire,

which, returning to the place it knew before,

will spread its greedy tongue

over your soft thickets. And unresisting,

you’ll bow your blameless head

under the deadly scythe;

but you will not have bowed before,

hopeless abject supplicant

of your future oppressor; you were never raised

by senseless pride up to the stars

or above the desert, which for you

was home and birthplace

not by choice, but chance

Leopardi was not a religious poet per se, but the poem ends on the biblical terrain where it began. In the allegorical tradition, the desert represents the wild, uncharted lands the Old Testament Jews led by Moses must traverse after they flee Egypt and make their painstaking way to the promised land. For Leopardi, analyst of the modern condition, there is no terminus, only a common point of departure and space of transition. Dante ends all three canticles in the Divine Comedy with a reference to the stelle (stars); Leopardi, half a millennium later, realizes such an allegorical option is no longer available, and so avoids the “senseless pride” that might occasion such a transcendental gesture. A lifetime of physical pain, exclusion from sexuality and society, meditation on the problems of existence, and vain yearning for his country to get its political act together failed to rid this most seemingly hopeless of poets of his faith in the reach of poetry. “Broom,” and effectively Leopardi’s career, end with an image of fragrance in the desert—and we are fortunate to have a translation like Galassi’s that captures and will, I hope, spread the scent.

Joseph Luzzi is associate professor of Italian and director of Italian studies at Bard College and the author of Romantic Europe and the Ghost of Italy (Yale University Press, 2008).