IF THAT SWEETMEAT of American Revolution agitprop called Johnny Tremain was ever a part of your childhood, then you probably encountered the illustrations of Lynd Ward. In one of them, we see Johnny slouching sadly by a wall, eavesdropping on Boston’s commercial life. A man in a cocked hat carries two long planks on his shoulder; a Puritan type strains backward, pulling a reluctant horse; somebody staggers under the symmetrical weight of two buckets. Johnny was a gifted (and arrogant) silversmith’s apprentice. Now his hand is crippled. His master has no more use for him. He must find a new place in this cruel world. Ward’s illustration, competent and even lively but all the same undistinguished, could never express this on its own. It is appropriate but dispensable.

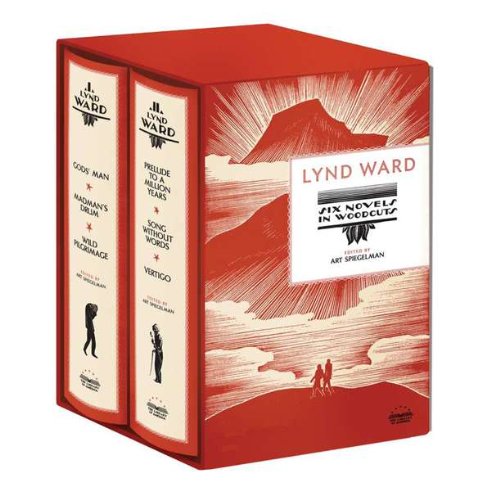

A rather different revolution was exemplified in Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl,” which, so the poet allegedly claimed, derived much of its fire from the graphic novels of Ward. These novels (1929–37) approach and sometimes attain genius. Unlike the illustrations for 1943’s Johnny, they stand alone without any text, a single woodcut on each right-hand page to tell their stories. All six of them have now been resurrected in an exquisite two-volume set by the Library of America, one of the very few publishers that still seems to care about the book as object. “I find it terribly difficult and even ridiculous to play the connoisseur and pontifically direct the attention of my readers to linear charms and God knows what other aesthetic ‘values.’ In this world it is no longer a question of such ‘values’: it is a question of genuine values, human worth, trustworthiness.” Thus Thomas Mann, 1926, in his introduction to Frans Masereel’s Passionate Journey, which is the most powerful graphic novel I know. Sympathetic as I am to Mann’s intention, I worry that in our world we often pretend that “genuine values” are enough, thereby atrophying our ability to appreciate those linear charms. Since much can be learned about beauty, meaning, and nuance by comparing the styles of wordsmiths, why not likewise distinguish between, for instance, Wardian and Masereelian technique?

What makes a Ward picture Wardian is its intuitive, partially spontaneous quality, which shines through increasingly if you scan the six novels in chronological order. At the beginning they look very much like the woodcuts they are, with all of that medium’s chiseled constraint. In time, they come to resemble lithographs. The lines grow more fluid, the shapes more volumetric. It is marvelous to see how the artist progresses from the Masereelian simplicity of Gods’ Man (1929), to the slightly more distorted, German Expressionist flavor of Madman’s Drum (1930), which is rich in grain and parallel lines, to the astonishingly lyric complexities of Wild Pilgrimage (1932), to the more lithographic look of Prelude to a Million Years (1933) and Song Without Words (1936), to Vertigo (1937), whose pictures remind me of those photogenic glass-plate drawings called clichés-verre. And so the argument might be made (wrongly, I think) that there is no one Wardian style at all. “Cutting for me must always allow a major amount of free play,” the artist once said. And again: By “seeking guidance from proofs of the unfinished block and attempting to incorporate qualities that result from the interaction between tool and material, the act of engraving takes on more of the aspect of a process of growth.”

And what, if anything, are his novels about but growth? Often, as in Vertigo, that growth matures into despair, but in Song Without Words it crystallizes into a resolution not unalloyed with hope. So how can I characterize his free play?

Ward is, to my mind at least, far more accomplished than Masereel if we simply compare the two artists block for block. A typical Masereel image is simple, a trifle crude, often sentimental or banal, sometimes outright forgettable. His genius has to do with sequencing. For instance, in Passionate Journey a man on his knees plays with a black kitten on the rug, while at the table a young girl holds her book open to wave at them. (Any illustration in Johnny Tremain is less forgettable—and sentimental—than this.) On the next page, a growing girl embraces her guardian at bedtime; the top of her head comes up to his chest; his hands are on her waist as she holds his neck. Turn the page, and a man carries a nubile young woman through the forest. These three consecutive blocks depict, with great economy of means, the progression of the affection between child and adoptive parent into an erotic and spiritual attraction between equals. You might consider Masereel a visual analogue to the great Japanese novelist Kawabata, much of whose effect is mysteriously elicited in the white spaces between words.

Between Ward’s images you will find less blankness than this. In Vertigo, for instance, the artist “was anxious to make as explicit a statement as possible. To accomplish that I broke down the action into many small steps.” If he had been telling Masereel’s tale, he might have taken five or six blocks where the German artist used only three, at least one of which would probably be a smaller, tight-framed close-up image of the man’s hesitating face or the girl’s shyness, puzzlement, or seductiveness. Masereel, by comparison, leaves it to us to micromanage the motives. Another point of distinction is that Ward’s images frequently contain zones that are neither black nor white, but striped, offering a greater variety of tone. Moreover, his figures are more individuated: the evil ones often skeletal or demoniacally dissected down to musclelike striations, the protagonists exquisitely curved along shoulder or haunch, and all bodies foreshortened or elongated in soulfully unpredictable ways. Sometimes Ward hints at the homoerotic. In his taste for muscular nudity surrounded by twinkling stars, he reminds me of Rockwell Kent. Finally, and most crucially, his individual scenes, unlike Masereel’s, can achieve artistic excellence in and of themselves. The very first full page of his third novel, Wild Pilgrimage, with its unraveling regiment of tired workers departing their sinister tower of industry, makes both an aesthetic and a political statement. Its aerial gaze is not only a perfect prelude to a sequence but also an assertion of the immense disparity in power between the urban hive and its insect-size inhabitants. In short, you may count on Ward not to carve the easy groove. Vital as they are, Masereel’s figures approach the generic; Ward’s frequently transcend it. This may have something to do with the fact that Masereel’s books are fables while Ward’s are at least sometimes polemics, hence must, one would think, “make as explicit a statement as possible.” But—curiouser and curiouser—Ward’s plots can sometimes be considerably more difficult to follow. Whether you prefer Masereel to Ward or vice versa may depend on how hard you like to work to understand a story.

Ironically, or perhaps tellingly, Ward’s first novel, Gods’ Man, is not utterly dissimilar from Masereel’s work. In one of the nine essays by Ward that the Library of America has helpfully appended, we learn that the artist once “believed that every block should be conceived in the simplest terms possible, then cut with an absolute minimum of tool work.” Thus the artist employed only one line-making tool for everything in the book except the white zones. But “now, with those earlier miles behind me,” he commenced his second novel, the enigmatic Madman’s Drum, and his own particular maturation into complexity made him dismissive toward Masereel’s simplicity. In their archaism of rigged ships and women’s long dresses, some of these blocks superficially resemble the illustrations to Johnny Tremain but vastly exceed them in compositional interest. Some are quite simply stunning. “I sought to develop a wider range of tool work and utilized small round gravers to break up a dark area with small jabs of a tool, thus achieving a variety both of tonal effect and textural quality.” We see the results in, for instance, the magnificent sixth image, in which the slave who stands on the auction block is jet black, the contours of his flesh defined only by a few delicate parallel scars of white light, while the leering auctioneer is one of Ward’s characteristic anatomized monsters, his musculature, hair, trousers, and striped shirt all seeming to pertain to a skinned cadaver. Meanwhile, the buyers, sky, and stacks of money offer us their own degrees of darkness. It is on the steps of the auction platform that we see these varying granules and polka dots of light that Ward effected with his “small jabs of a tool.” The rest is almost entirely white, black, and stacks of lines.

I said that Madman’s Drum is enigmatic, and indeed it is, almost to opacity on a first perusal. This novel deserves deep study, and I wish I had the space here to admire it further, or Wild Pilgrimage, which is my favorite. (By the way, the Library of America has shrunk this novel’s images slightly; to enjoy them at a larger size, see George A. Walker’s compilation Graphic Witness: Four Wordless Graphic Novels, which, however, settles for reproducing them on facing pages, an economy that the Library of America proudly eschews.) But perhaps it will suffice for us to consider the first few pages of Vertigo, his last and longest graphic novel.

The opening chapter is called “The Girl.” We watch its subject grow up rapidly into a talented and perhaps acclaimed violinist. The four woodcuts that tell this tale do not bear a fraction of the emotional content found in those previously noted pages in Passionate Journey. But that must be because Ward does not wish for too much emotional content just yet. His theme here is aspiration, accompanied by the innocent complacency characteristic both of youth and of affluence, the latter quantity bidding us good-bye suddenly as we turn the page to meet the title of the second chapter: “1929.” And we see a lovely woman, presumably the Girl, stretching in her boudoir, naked, powerful, languid, satisfied. Either Black Thursday has not yet arrived or else the Girl doesn’t understand stocks. Never mind. Call this third-person omniscient narration; you and I have just been clued in on the likelihood that she will meet an unpleasant future. Fully dressed, she now stands smilingly, waving her hat to the man whom I suppose to be her father or guardian, who gazes up at her from the newspaper, startled by her presence or, it may be, shocked by the financial news. From far away, we next gaze through the futuristic underbelly of what could almost be Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, picking out, through streetlights, immense girders, and crosshatched shadows, the Girl about to descend the steps but facing her guardian, holding his hand as he on a higher step bends down to her, but with his free hand drawn back in an ambiguously intimidating gesture. Down in the underpass where she will soon go, three men lean near one another in rays of light. Perhaps they are strangers waiting for a train, or it might be that they are getting drunk. We will never know their story. Thus the mysterious night world of our cities, which Ward evokes so well. This woodcut is sufficiently beautiful to stand alone.

And now, on the next page, many people stream in the light rays between dark columns toward some unknown goal. In the foreground, a woman takes a man’s arm. We see this woman only from behind, but from her narrow waist and the style of her skirt she might well be the Girl. Is she? Turn the page. A man sits among other spectators, with concentration on his face. Is he attending one of her performances? Turning the page again, we certainly expect to see the Girl by now, but instead, on a stage by a podium, here stands a suited orator in pince-nez, one hand on his hip, the other gesturing toward heaven. What can he be about? Although his face is more elongated, he slightly resembles Trotsky in Robert Capa’s famous photoportrait, but that was taken in 1932, not 1929. Hoping to learn more about him, I turn the page, only to find a sailing ship on the high seas. Next appears a troop of ax cutters, and then I find a man who grips a rifle while he plows. In the distance, I glimpse a martial figure. Now comes a workman of some kind, evidently a builder. Then several people are shooting rifles, in which case they must be engaged in warfare. Wagons roll toward the mountains. Herculean railroad men raise hammers. A man fastens a bundle for the hook of a construction crane. And now here stands the orator in pince-nez again, with cities and mountains at his back; he is declaiming, and in his upraised hand he holds a rolled document.

Graphic novels sometimes require of us the willingness to see and remember without comprehending right away. Sometimes we will never understand it all, which might even be the artist’s intention. Ward evidently wishes us to consider the Girl as a part of some complex human world of commerce, change, and tumult. In his brief essay on Vertigo, he mentions “the obvious effect that vast, complicated, and impersonal social forces were having on the substance of so many individual lives.” Somehow that ship sailing somewhere unknown and those ax cutters will, as the Depression tightens, affect the life of the Girl even if their existence never becomes manifest to her. On the next page we have returned to her at last. She stands in line to receive what must be her diploma, evidently from a conservatory of music. (The similarity in shape between what is offered to her and what the pince-nezed orator holds suggests that he, too, has a document; perhaps it is the Treaty of Versailles or some promise to soldiers or workers. Never mind; I’ll be patient.) Having seen her graduation, I can better comprehend Vertigo’s opening sequence: She must not yet be famous, merely promising; but surely she is, as they say, “going places”—in 1929.

Well, turn the page. Everyone is going home. The Girl holds her diploma, walking side by side with a man. Is he the one who was in the audience? Possibly; probably. The next woodcut is smaller, intimate. Peering over her shoulder, a young man whispers into the Girl’s ear. The older man stands with them but in the background, perhaps unknowing or unheeding. But in the next block, the Girl speaks to him. Then the Girl and the young man stand under a streetlight, serious and awkward. The woodcut movie camera now pulls back, and we see them from behind, side by side, not touching, small and vulnerable as they stroll through a shaft of light between two silhouetted urban towers. (Were I to give Masereel his due, I’d confess that this particular woodcut is not artistically superior to any in Passionate Journey.) And for a moment I wonder how the novel would look had Ward cut every block of Vertigo to his highest standard. But perhaps his intention is to speed us through the prelude. He begins his essay on the book as follows: “I sometimes wonder how many of those who live in this great metropolitan area remember, as they drive along Manhattan’s West Side Highway and make the swing at Seventy-second Street to the elevated structure that carries the roadway on down between the city’s docks and warehouses, that in that spot in the early thirties there was a Hooverville.” The extreme specificity proves the importance of this spot to the artist, and indeed you will see it several times more in Vertigo. When I come to one of these lovingly rendered images, my inclination is to pore over it, trying to see and feel as much as I can. And it is just these that I most remember and want to gaze at again. Since Ward possesses this power to arrest my attention, why not postulate that he withholds it on purpose? Seen in such a light, much of the 1929 chapter becomes the bitterest satire on blindness’s myriad banalities.

In any event, because Vertigo is a highly effective sequence, the story itself has already seized hold of me, and so I perceive this picture of the couple beneath the streetlight as a constituent of a continuing scene whose unfoldings I wish to know. Accordingly, I turn the page. I see them entering some pleasant, crowded outdoor event. Now they are arm in arm. Turning the page again, I discover them encountering one of the bearded, turbaned fortune-telling swamis of that epoch. YOUR FUTURE: 10¢. And so I realize that the previous picture must have represented some fair or carnival. The swami gazes blearily into his crystal ball. The young couple peer down likewise, with supernatural light gilding their fine young eye sockets. Now Ward lets us see in as well, and we discover the Girl playing her violin before a crowd. Next, the crystal ball shows us the future of her prospective life partner: He is working with a crane hook. So that man who was fastening the bundle several pages back must be this likely proletarian fellow. Well, good luck to both of them! Holding hands, our couple half-stride, half-dance forward among other young couples, straight into their future. They ride a merry-go-round and consider a large, shining ring. And so they frolic away the rest of 1929, until a thunderstorm disperses everyone. Turning the page, I find myself about to enter 1930. And now the vertigo begins.

More than ever we need artists like this: People who can draw (or carve), who pay some attention to history and politics, and who suffer for the sufferings of others. As it says in Johnny Tremain (and perhaps this is why Ward chose to illustrate it): “Hundreds would die, but not the thing they died for. ‘A man can stand up.’”

William T. Vollmann’s latest book is Kissing the Mask (Ecco, 2010).