I.

Painting a word-picture of a woman at a restaurant, the titular narrator of British author Jonathan Coe’s new novel, The Terrible Privacy of Maxwell Sim, writes, “She had long black hair, slightly wild and unkempt. A thin face, with prominent cheekbones.” Prominent cheekbones? Just as the cliché meter is warming up, Max adds a parenthetical: “(Sorry, I am just not very good at describing people.)” This self-deprecation is enough to win us over, and it lets Max off the hook to unleash a few more lines of workmanlike, tentative details . . . prompting another aside: “(I am not very good at describing clothes either—are you looking forward to the next three hundred pages?)”

Max is that tricky creation: a nonwriter, with zero interest in books, who is writing his own story. (Told that he might broaden his horizons with one of the Rabbit books, he buys Watership Down.) For the author, it’s a way of writing about writing without getting too inside-baseball. Max’s allergy to literature might explain his two failed relationships: with Caroline, now his ex-wife, a budding fiction writer who lately has “found a good writers’ group to attend every Tuesday evening in Kendal”; and with his widowed father, an abstruse poet who moved from England to Australia two decades ago.

Antibookish Max’s charming interruptions also foreshadow what will be the MO of this enjoyable and generous novel, at once a surprising love story and a meditation on the myth of modern connectivity. (Yes, Facebook is mentioned.) Max is a self-described “After-Sales Customer Liaison Officer for a department store in central London,” on leave for depression after the collapse of his marriage; later, he will take on a new job as a traveling PR man, assigned to hawk eco-friendly toothbrushes in the country’s farthest reaches. He is, to all appearances, the soul of dullness. The point is brought home when, in a sincere attempt to be extroverted, he tells his life story to a seatmate on a flight from Australia back to England—a rambling monologue cut short when his listener croaks.

As if to prevent our death by boredom, Coe complicates Max’s account by having his hero encounter four documents written by others, which are reproduced in full. Each one is a revelation to Max, and each is a tight, powerful story in its own right. After his first seatmate expires, he hits it off with the replacement, a young woman, Poppy, who allows him to read a long and fascinating letter from her beloved Uncle Clive. Clive relates the haunting story of Donald Crowhurst, a British sailor who in 1968 entered a contest to circumnavigate the world. Unseasoned and ill equipped, Crowhurst fudged his position (a fraud possible in the days before satellite navigation) to the delight of his countrymen, but wound up going mad—his breakdown preserved in his logbooks—and disappearing forever. The second text is Caroline’s, a fictionalization of a disastrous vacation with Max, their daughter, and another family; though she subjects Max to devastating analysis, he admits that she’s transcribed his thoughts “85 percent accurately.” Later, he discovers an old university essay written by a childhood friend’s sister, about a “privacy violation” from their past; the final non-Max story is a memoir of his father’s early failures, artistic and financial, in London, and subsequent entry into a loveless marriage.

The book’s structure is elaborate, even dizzying. The first four sections of straight Max narration are titled, mundanely, after his points of transit, by plane or Prius: Sydney–Watford, Watford–Reading, et al. Each section contains an embedded story, which Coe gives an individual title (e.g., “The Nettle Pit”), as well as an elemental one (“Earth”) somehow related to it. Why has Coe built such a sophisticated structural conceit around someone who declares without irony, “I really like the way you can drive into almost any city nowadays and be sure of finding the same shops and the same bars and the same restaurants”?

Maxwell Sim sometimes introduces himself as “Max, for short,” and “like a SIM card,” referring to the “subscriber identity modules” found in cell phones, which allow users to transfer essential information from an old electronic device to a new one. Throughout the novel, Coe is eager to capture The Way We Live Now, incorporating all manner of our current modes of distraction, aggravation, and communication, from scouting out cafés via Google Maps to falling in love with the voice of your GPS interface. (Max calls his “Emma,” her calmly repeated instructions to “proceed on the current motorway” sounding like a lobotomized Greek chorus.) This commentary doesn’t always cut as deep as it should (see the ludicrous tool-enhancing spam that simmers in Max’s in-box, which might as well have been written in 1998). But when Coe’s on target, the results are inspired: Max is able to read Caroline’s story because he’s won her confidence by commenting on a moms’ discussion board as “SouthCoastLizzie,” aka Liz Hammond, a make-believe “single mother from Brighton with her own little business making items of jewellery and suchlike.”

That Caroline and Liz hit it off better than Caroline and Max ever did is both sad and metaphorically rich. Max Sim is a SIM card: an everyman, rubbed nearly anonymous by life, who might as well be a string of digits, yet on whom we will focus the maximum attention. But the temporary transformation of Max into Liz brings up another possibility, another resonance—that a person can progress to higher levels of awareness, in the way that a SIM card can be removed from a simple device and placed in ever more sophisticated ones.

II.

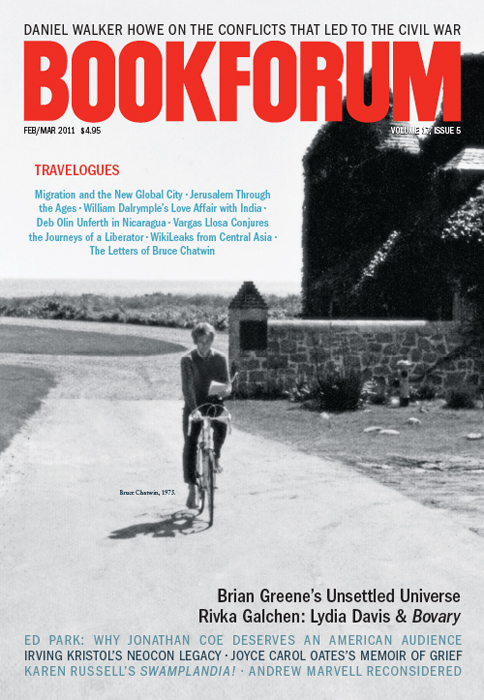

How can it be that Jonathan Coe is still obscure in this country? This isn’t the usual cri de coeur of the out-of-touch critic, bemoaning an artist’s failure to receive his or her due. (I think of the cinephile in Coe’s 1998 novel The House of Sleep, championing an Italian director whose great lost film, Latrine Duty, is “a hymn to the degradation of the human spirit.”)

The other night, after several days of enforced and enjoyable reacquaintance with the Coe canon, I went to a party, where I tried to find someone with whom I could rave about Coevian greatness. One writer I met said, “I think I’ve heard of him . . . Palladio?” Ten minutes later, another narrowed his eyes as he searched for some connection, coming up with the hopeful “He wrote . . . Witz, right?” Jonathan Coe isn’t Jonathan Dee or Joshua Cohen, though I’d wager that fans of either of those writers might enjoy his books. On the one hand, his novels are immensely pleasurable in traditional ways: rich in characterization, emotionally resonant, thoughtfully plotted. (Coe is a master of the well-placed shock—the often literally jaw-dropping surprise that, in fact, has been carefully prepared from the beginning.) On the other, he’s committed to unorthodox, even daring formal conceits, which energize his books by shaking them out of any possible complacency.

The novels can be socially engaged (his 2001 masterpiece, the antic but essentially realistic The Rotters’ Club, unfolds against a tumultuous labor situation in 1970s Birmingham) or politically scabrous (his 1994 masterpiece, What a Carve Up!, published in the US as The Winshaw Legacy, dissects, as it were, the fat cats of Thatcherite Britain) or not much of either (the pure threnody of 2007’s underrated The Rain Before It Falls, which I’m going to call a masterpiece as well).

Coe manages all that—great plots, complex interweave of characters—while also being very, very funny. There are many contemporary writers who can make you laugh, but Coe is one of the few whose comic set pieces do that and feel like miniature works of art. He has a genius for perfectly constructed jokes with hilarious payoffs, like the missing superscript that derails a set of footnotes in The House of Sleep, turning them into an obscene commentary. One suspects The Rotters’ Club included a character’s high-school-paper review of Tales from Topographic Oceans mostly so Coe could use this line: “In conclusion, if someone was to ask me who this album was by, and whether or not it was a masterpiece, I would be able to give the same answer: YES!!”

A key to Coe’s art—and in particular this latest novel—can be found in Like a Fiery Elephant (2005), his spookily good biography of B. S. Johnson, the British fiction writer, filmmaker, and unrepentant enemy of the conventional novel. Johnson’s aggressively original books include House Mother Normal, whose seven parts transpire simultaneously, each (save the last) reproducing the gapped-out thoughts of progressively more senile nursing-home patrons. But his most radical novel, The Unfortunates (an interior monologue divided into twenty-seven pamphlets that the reader plays on shuffle), is also his most personal—and his best. This record of Johnson’s friendship with Tony Tillinghast (an academic who died young of cancer) is loquacious and touching, and most poignant when white space spans the margins, an art of confession and absence.

The similarities between Coe, who is traditional in his devotion to story, and Johnson, whose feisty credos included “Telling stories really is telling lies,” aren’t immediately obvious. Nevertheless, Coe (who spent nearly ten years writing Elephant) calls Johnson one of his “greatest literary heroes,” for “his command of language, his freshness, his formal ingenuity, the humanity that shines through even his most rigorous experiments, his bruising honesty.” Most central to his appeal is “the simple reason that he took himself, and his art . . . so seriously.”

Because, in spite of what he said, it’s not the reactionaries or the old fogeys who pose the greatest threat to the novel. It’s the dilettantes. The gentlemen (and -women) amateurs. The resting actors and the bored journalists and the ubiquitous media people hungry for kudos and the talented but directionless Oxbridge graduates who’ve all got agents queueing up to take them out to lunch. And because it’s so easy for these people to get published, we end up with bookshops piled from floor to ceiling with novels that aren’t really novels at all, written by people who haven’t given the form and its possibilities a tenth of the thought that B. S. Johnson gave to it before he even set pen to paper.

The form and its possibilities. A heterogeneous approach to narrative material might make for a crowded table of contents, but it gives some indication of the amount of care the author has taken in his attempt to achieve certain effects. Anyone might have come up, in abstract, with the chain of multigenerational sadness related in The Rain Before It Falls. But it’s the peculiar way that tale is transmitted that heightens its impact. An ailing woman describes, on tape, twenty family photographs, for the benefit of a blind relative she might never see again—it’s practically an Oulipian constraint. The Winshaw Legacy, the immense, five-hundred-page satire that made Coe’s name in the UK, maintains its aim, ironically, by its constant, protean motion: assorted POVs and tenses, news clippings, transcripts, diaries, ads, and more. All of this is set in a frenetic, ultimately ouroboric structure, yet the reader never gets lost in the fun house.

III.

Like a Fiery Elephant explicitly informs The Terrible Privacy of Maxwell Sim. B. S. Johnson killed himself in 1973, at age forty—a shock, if not a wholly unanticipated one. (He was no stranger to depression and suicidal thoughts; during his twenties, he believed with superstitious clarity that he would die before thirty.) Still, in writing Like a Fiery Elephant, something about Johnson’s death doesn’t sit right in Coe’s mind. Scrupulous with facts, Coe reserves the most hair-raising shock for the coda (“Fragment 46”). Here the book turns into a thriller of sorts, as we get a closer look at a shadowy figure, Michael Bannard, only glimpsed earlier. Bannard and Johnson bonded after meeting while working in the London offices of the Stanvac Oil company; judging from Johnson’s diaries and other writings, Bannard exerted a powerful, even frightening influence on him, until the novelist was able to make a clean break in 1955. Or so it seemed. The real shock of the biography, uncovered in this last section, is that Johnson met with Bannard on the night before his suicide.

Johnson’s widow relates a contemporary’s comparison of Bannard to Aleister Crowley, though as Coe digs deeper, he finds this portrait somewhat exaggerated. Accounts of Johnson in the prime of his career make him seem larger than life; Bannard, at this earlier moment, was even more so. “Bohemian, homosexual, culturally omnivorous, overbearing, exasperating,” he wore a cape, attended musical performances that he made a point of heckling and leaving, and was a student of “esoterica and occultism.” (Johnson’s diary suggests an overture from Bannard, which he resisted.) In later years, he lived nomadically in Asia, working as a language tutor.

Bannard wove a spell around Johnson and has clearly possessed Coe’s imagination as well. In The Terrible Privacy of Maxwell Sim, Coe transmutes this mysterious, sexually charged episode of Johnson’s life into fiction. An insecure young poet—Max’s father—comes to London in 1958 and meets a cape-wearing, concert-disrupting, art-inhaling man whose charisma is irresistible. The Johnson-Bannard dyad’s fixation on witchcraft and Robert Graves’s The White Goddess is alluded to, and the Bannard figure (I’m skirting spoiler-alert territory here) implores his companion:

Don’t become one of those lesser mortals who inhabits the material world. The world where people spend their lives making things and then buying and selling and using and consuming them. The world of objects. That’s for the hoi polloi, not the likes of you and me. We’re above all that. We’re alchemists.

Coe’s cover version takes seriously the occult preoccupations of its model. The alchemical elements are Water, Earth, Fire, and Air—the very tags, of course, that Coe has given to the four self-contained narratives in this novel. Is the leaden Maxwell Sim, that lifelong dweller in the world of objects, being prepared for some more rarefied transformation? “Fairlight Beach,” the book’s final section, is the only one in which Max spends most of his time outdoors, right where sun, surf, sand, and sky mingle. His story seems headed for a happy ending, a rarity in Coe’s novels.

But not so fast. As in Like a Fiery Elephant, Coe reserves the most brain-scrambling shock for the very end. The brief final section of Maxwell Sim, which features an appearance by Coe himself, at first irritated me—the sort of cute postmodern touch that seemed hardly simpati-Coe. On a second read, though, it became chillingly brilliant. The coda violates Max’s privacy in a way that goes beyond simple plot and completes a startling transformation, albeit not the alchemical one that’s been lurking. Instead, for the careful reader, the section’s mathematical title, “√-1” (so short I initially didn’t notice it), hurls the book backward, to a minor passage hundreds of pages earlier, in the story of the doomed sailor Donald Crowhurst. Crowhurst, radioing false positions in 1969 as he pretended to circle the globe, committed to his logbook this insane-sounding musing on the square root of minus one: “Once technology emerges from this tunnel [of the space-time continuum] the ‘world’ will ‘end’ . . . in the sense that we will have access to the means of an ‘extra physical’ existence, making the need for physical existence superfluous.” By the conclusion of The Terrible Privacy of Maxwell Sim, which takes place in a world where our threshold technologies allow for an existence unthinkable in 1969, these ravings of a desperate deceiver have a prophetic edge. We now have dozens, even hundreds of “friends,” many of whom we’ve never met, relationships we can terminate with the proverbial click of a mouse. One is the loneliest number; the square root of negative one, the impossible number, a kind of annihilation. Coe, seen by one of his creations as having “the eyes of a serial killer,” ruthlessly follows through on this monstrous logic.

Ed Park is the author of the novel Personal Days (Random House, 2008).