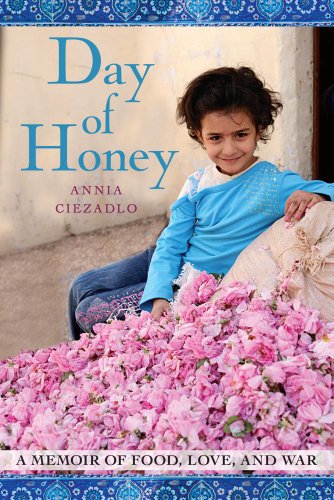

“One of the secrets of life during wartime,” writes Annia Ciezadlo in Day of Honey: A Memoir of Food, Love, and War (Free Press, $26), her chronicle of eating in Baghdad in the months after the 2003 invasion of Iraq and in Beirut during the 2006 war with Israel, “is that your senses become unnaturally sharp, more attuned to pleasure in all its forms. Colors are brighter, more saturated. Smells are stronger. Sounds make you jump. Music makes you cry for no reason. And food? You will never forget how it tastes.” In the days after a nasty outbreak of sectarian violence, she asks a Lebanese cheesemonger, “Why? Why, in the middle of a firefight, do people decide that they must have cheese?” to which he replies, “Because they think they will never be able to taste it again.”

Of course the truth, like all so-called truth during wartime, is more complicated than that. But the cheesemonger’s answer serves as a neat summary of what lies at the heart of Ciezadlo’s story. Equal parts history of the Middle East, tale of cross-cultural marriage, and riveting account of life as a civilian reporter in two war zones—she was a correspondent for the Christian Science Monitor and the New Republic—Day of Honey is first and foremost a paean to the powers of food, recipes included.

Her odyssey begins in New York, when Mohamad, her new boyfriend and fellow journalist, takes her to his favorite restaurant in Queens, the Afghan Kebab House. Before long, September 11 descends and he’s on his way to Pakistan, from where, instead of discussing the intricacies of chicken kebab in yogurt sauce, he says things to her like “Annia, there are wild dogs here. . . . I’m standing out in the open trying to get a satellite signal and they’re starting to circle around me. I have to go.” A year later, Mohamad is appointed Newsday’s Middle East bureau chief, and the couple, now married, move to Baghdad, where one of the jokes going around among expats is that the real weapon of mass destruction is the Iraqi food being served to foreigners in their hotel restaurants.

Thus challenged, Ciezadlo sets off in search of the real thing; she discovers masquf, a wood-roasted river fish traditionally served along the banks of the Tigris that is not only delectable but heavy with meaning. “There was a phrase Iraqis were always using: the flavor of freedom,” she writes. “For a lot of Baghdadis, that flavor was masquf. It was more than just a fish, or a way of preparing it; the ritual of masquf embodied a vanished place and time.” After a year has elapsed and the war is on full-blast, this culinary national treasure is just another piece of collateral damage. “Militants would fire mortars across the river into the Green Zone; the U.S. military would return fire,” Ciezadlo recounts regretfully. “The few surviving masquf restaurants, which were hardly ever open, would occasionally get hit.”

Around this time, unsurprisingly, she finds her nerves so shot from the ravages of war that she sheds ten pounds in as many days. When she finally regains her appetite, she heads off to one of her favorite local restaurants and gets food she doesn’t expect, as well as a lesson in cooking to save yourself and your dignity when the world is literally crumbling around you. On arrival, she finds that “for some reason the chef had chosen that particular moment in late May 2004—during the Mahdi Army uprising, the first Marine assault on Fallujah, and the Abu Ghraib court-martials—to make a chicken roulade stuffed with cream sauce. It was a beautiful thing.” She inquires as to why, lacking electricity, let alone normalcy, he has bothered to go to such lengths. “An expression of pride and despair, halfway between a smile and a sigh, flickered across his face,” she recalls. “‘It’s what I do,’ he said.”

It’s what Ciezadlo will do to counter the chaos, too, following a path she’s been well prepared for by a peripatetic childhood in which “there were days when we didn’t know where we’d be sleeping that night; months when I longed to go to school like a normal kid. But one thing I never questioned: dinner.” In 2004, she and Mohamad move to Beirut to escape the violence and stress in Baghdad. Their new living space is a tiny hotel suite, but even so she can’t help herself. “The more rootless I felt, the more I cooked. I spent hours in the little dollhouse kitchen assembling pathologically elaborate meals,” she confesses. “These ornate concoctions were a substitute for something else, something just out of reach. . . . I wanted a time and place where people who loved each other sat around a table and conversed. Breaking bread was the oldest and best excuse for such an occasion.”

And so she devises a scheme to start cooking with her fabulously passive-aggressive Lebanese mother-in-law, who has recently moved in following surgery and is driving the couple insane. “I would ask Umm Hassane to teach me how to cook traditional Lebanese food, under the pretext that I needed to prepare food for Mohamad, like a dutiful wife. . . . I would learn something new; she would have a mission, something to make her feel appreciated.” The plan works. Ciezadlo collects an arsenal of recipes to wield against her nomadism, while her husband’s mother gets to harass her about not having a baby. And somewhere, amid the onions and eggs and kibbe and stews, the two women find a kind of peace.

By the time Hezbollah starts launching rockets into Israel, Ciezadlo finally has the kitchen she’s longed for, complete with a view of the sea she describes, with the clear-eyed delicacy she brings to everything from a finely prepared plate of fattet hummus to a pile of rubble, as “a trapezoidal sliver of Mediterranean water, which was a different color every day, a giant mood ring for the city.” As Israeli bombs thunder down, Ciezadlo writes, “all of Beirut answered the call, preparing for war with an ancient Lebanese tradition: grocery shopping.” At the same time, she finds her neighbors and relatives recounting stories of life during Lebanon’s 1975–90 civil war. Many involve food: There were the brothers in different militias who remained neutral only when they encountered each other at the local bakery. There’s a friend’s recollection that “sometimes militiamen would take over an entire bakery: if they controlled the bread supply, they controlled the neighborhood.” Ciezadlo makes a point of emphasizing the power of food in war, and not just as sustenance. “War is part of our ongoing struggle to get food,” she reminds us. “Most wars are over resources, after all, even when the parties pretend otherwise.” And in Baghdad, she meets Alan, an American officer who heads a unit

responsible for building relationships between the U.S. military and the local population . . . one of the most important acts of diplomacy an American soldier could perform, as Alan soon discovered, was simply to eat. Eat the sheep a tribal sheikh has slaughtered. Eat mountains of rice scooped up with three fingers. Eat gobbets of fat with relish, and not a moment’s hesitation, because your host would normally save this delicacy for himself and he is offering it to you min eedu, from his hand. . . . The path to hearts and minds led through the stomach.

It’s a poetic, not to mention truthful, understanding of the culture Ciezaldo has chosen to steep herself in, but one of the great strengths of her book is that as enthusiastic as she is, she never loses her ability to cast a necessarily cold eye on the goings-on around her. “There’s a saying in Arabic: Fi khibz wa meleh bainetna—there is bread and salt between us. It means that once we’ve eaten together, sharing bread and salt, the ancient symbols of hospitality, we cannot fight,” she writes. “It’s a lovely idea, that you can counter conflict with cuisine—and I don’t swallow it for a second.” All the same, her book is a passionate argument for the idea that whether it’s your mother-in-law or a military enemy, meeting over a meal eases differences, and that knowing the world means dining in it.