By the early 1970s, American television comedy from Los Angeles had finally caught up to the ’60s, with hit shows like MASH, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, and Norman Lear’s slew of liberal social-realist comedies—All in the Family, Good Times, Maude, and One Day at a Time, to name a few—which turned America’s sitcoms into a panorama of political, gender, and racial humor. Then in 1972, a PBS station from culturally conservative Dallas became the first American outlet to broadcast the highbrow silliness of Britain’s Monty Python’s Flying Circus. If the Pythons had little to say about topical issues, they made the most formally innovative TV comedy seen here since The Ernie Kovacs Show, one comparable to the cinema of Buñuel and Fellini. And the first Python anyone ever saw was Michael Palin, as a bearded madman staggering out of the desert, ocean, or jungle, struggling just to croak out one word, “It’s”—before the riot of Terry Gilliam’s opening titles.

Like all the British Pythons (Gilliam is an American), Palin came out of “Oxbridge”—from the two comedy clubs of Oxford and Cambridge. He graduated Oxford in 1965, in the era immediately after Beyond the Fringe, the stage revue in which Peter Cook, Dudley Moore, Alan Bennett, and Jonathan Miller made highly educated British humor the fashion. Palin and his Oxford writing partner, Terry Jones, worked on several BBC comedy shows before joining Cleese, Graham Chapman, Eric Idle, and Gilliam in 1969.

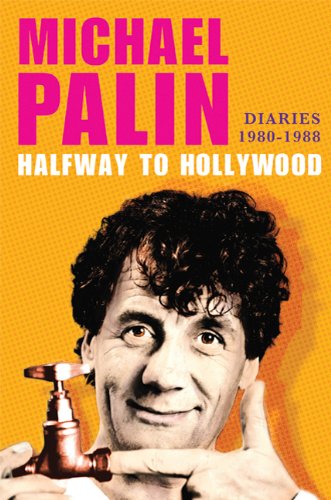

Palin’s first published journals, Diaries 1969–1979: The Python Years (2006), cover the Pythons at their peak, from their debut through Monty Python and the Holy Grail and Life of Brian. Compared with Chapman, who daringly lived an openly gay life by 1970, or Jones, whose sexual adventuring in orgies and at strip clubs only briefly surfaces here, Palin is pretty straitlaced. A husband and father before any of his colleagues, married still to his wife, Helen, he describes himself as left-wing, “moderately so.” Palin dislikes Thatcherism in England, but he’s no rebel. He rushes across town to be on hand when Princess Margaret turns up at a screening of his film. To date, he is the only Python to receive a CBE from the Queen.

Palin’s title for volume 2, Halfway to Hollywood, is a reference to his courting of American movie stardom. And fittingly enough, his 1980–88 diaries offer an impressive list of celebrity supporting players. With Terry Gilliam, Palin wrote Time Bandits, and he costarred as creepy Jack Lint in Gilliam’s Brazil. His backer in Britain was George Harrison’s HandMade Films, and Palin appeared in Python’s Meaning of Life and Live at the Hollywood Bowl, Cleese’s A Fish Called Wanda, and Bennett’s A Private Function. Unfortunately, Palin’s own film, 1982’s The Missionary (which he wrote, produced, and starred in), failed in the United States after his studio marketed this gentle comedy about a missionary trying to save the souls of sex workers in a brothel (and getting seduced by them in turn) as the new Porky’s or Stripes.

Boldface names aside, many of Palin’s entries are long and mundane. At one point, Palin writes that Jones “told me to stop playing such dull characters!”—a sentiment that readers may well endorse. We get many visits to the doctor, many British entertainment producers and functionaries American readers will most likely not know, and, one senses, mere scraps of Palin’s views of Python frictions and the darker sides of his fellow troupe members.

In 2011, Palin’s 1980s genteel comfort zone of British class and culture feels distinctly confined. He records a discomfiting awareness of Jews—finding people and places “very Jewish,” dismissing scripts with too many “Jewish one liners.” There is Palin’s newsstand vendor, an immigrant identified as Mr. Nice Man (Palin commends his hardworking ethic). Odd moments of self-congratulation appear, such as Palin meeting a man with AIDS and noting, “Like Princess Di I shake his hand and feel no threat.” Palin is no bigot—but this quote is from the ’80s, not 2011, and he’s clearly not used to melting-pot Britain.

By 1986 the Pythons had lost their co-medic cachet with the rise of the UK’s alternative comedy scene, which boasted figures such as Rik Mayall, Ade Edmondson, Lenny Henry, Ben Elton, Jennifer Saunders, and Dawn French, who would create comedies like The Young Ones and Absolutely Fabulous. Watching BBC execs hang on them at a party, Palin writes, “These enfants terribles of alternative comedy. They stand comfortably and confidently at the centre of things, the new establishment. Still, there could be much worse establishments.”

And Palin, after all, is a man who likes establishments. It’s in this volume that his career as global railway documentarian, as the host of a long-running BBC series, takes him from one passion, comedy, to a second, world travel. He’s gaining a new audience, shifting from Anglophile college students to British retirees. This is also where Palin leaves us. He’s about to re-create the Around the World in 80 Days journey, with Python fans aware that Chapman’s death from cancer is just around the corner in 1989. For a generation that knows Palin’s work best from the musical Spamalot or reruns of his absurdist television show, his diaries often conjure the complacent world he once so artfully sent up.

Ben Schwartz is a screenwriter and journalist based in Los Angeles.