Imagine if the most cunning and cosmopolitan poet of our era—John Ashbery, say—were a progressive US senator from a small state far from Los Angeles, New York, or Washington, along the lines of Bernie Sanders. Envision, too, that this poet/politician hides out in the margins of his poems, such that his angle on any subject, philosophical, religious, or political, atomizes into irreconcilable fragments—except that he also writes fierce, polemical pamphlets, though often without signing his name to them, and maneuvers under threat of exposure and censure. Consider that he has no fixed abode; vanishes abroad, after the fashion of Valerie Plame, on obscure intelligence operations; might not be married to the woman who says she is his wife; and once memorialized his own experiences in a letter as “But I my self, who live to so little purpose.” Try to resolve these shadows before rumors slip into legend, and the upshot is someone like Andrew Marvell—The Chameleon, as Nigel Smith dubs him in his exhaustive, shrewd, wary new biography.

Why Marvell? Why now? First there is the claim of art. This preternaturally sophisticated seventeenth-century poet will be familiar to modern readers from a scattering of exquisite anthology set pieces, notably the witty, borderline creepy “To His Coy Mistress” (“My vegetable love should grow / Vaster than empires”) and “The Garden.” These are, respectively, the most audaciously original carpe diem and garden poems in English. Yet if one were inventorying a sort of best-of-genre checklist, Marvell would in turn be the author of the finest, and strangest, country-house poem (“Upon Appleton House”), as well as of the strongest, and oddest, definition poem (“The Definition of Love”), Horatian ode (“An Horatian Ode upon Cromwell’s Return from Ireland”), complaint poem (“The Nymph Complaining for the Death of Her Fawn”), and political satire (“Last Instructions to a Painter”). Astonishing aim, particularly for a poet whose canon, counting juvenilia, Latin and Greek pieces, and collaborative satires, tallies less than seventy titles.

Even as his poems glanced back toward Horace, Lucan, Ovid, and Catullus, Marvell—perhaps more than any other English classic—anticipated our own aesthetic conundrums and obsessions: appropriation, collage, instabilities of language and form, representation, contradictory interpretations, and the elusiveness of the self. Perhaps the most recurrent pivot in his poetry is a debate between articulated styles of living, sometimes signaled in his titles—“A Dialogue, Between the Resolved Soul, and Created Pleasure”—sometimes dramatized through the clashing dictions of the poems themselves: the strains of pastoral love and eroticism in “The Picture of Little T. C. in a Prospect of Flowers,” the counterpoints of devotional simplicity and artistic ingenuity in “The Coronet,” and the Royalist and Republican stresses in “An Horatian Ode.” Most original when most allusive, Marvell tracked the mind in motion across divergent cultural traditions and shifting internal perspectives, with a conspicuous empathy for extreme psychological and social states.

Consider this whirligig from “Upon Appleton House”—a nearly eight-hundred-line poem likely composed in 1651, while Marvell was serving as tutor to Mary Fairfax, daughter of Lord Thomas Fairfax, then in retirement at Yorkshire after commanding the Parliamentary army during the English Civil War. Just prior to the stanza, some fantastical mowers (“men like grasshoppers appear, /But grasshoppers are giants there”) start to scythe the grass, and after them come a herd of grazing cattle—cattle Marvell runs through dizzying transformations:

They seem within the polished grass

A landskip drawn in looking-glass.

And shrunk in the huge pasture show

As spots, so shaped, on faces do.

Such fleas, ere they approach the eye,

In multiplying glasses lie.

They feed so wide, so slowly move,

As constellations do above.

Marvell, like Flaubert’s God, inheres in details. Earlier, he welcomed the mowers as though they were players in a masque (“No scene that turns with engines strange / Does oft’ner than these meadows change”), and the cattle soon enact a comedy of slippery, mutating scale, as neither the world nor the language for describing that world will stand still. By way of a pun on “polished grass” and “polished glass,” Marvell thinks the cattle look like they are within a landscape painted on a mirror—a seventeenth-century art vogue. Next he imagines someone looking into the mirror, so that the cattle resemble blemishes on a face. The diminished cattle, now “spots,” remind him of fleas, but fleas then viewed through a microscope (“multiplying glasses”), such that they—simultaneously cattle, spots, and fleas—emerge as large as stars. With so much in motion, Marvell accents his own self-consuming theatricality as a poet through insistent readjustments—skeptical and polymorphous. A few stanzas back, he compared the mowers to the biblical chosen people (“The tawny mowers . . . seem like Israelites”) crossing not the Red but “a green sea,” and, amid one of the bravura self-reflexive turns in literature, the mowers brutally reject his analogy—“He called us Israelites”—spotlighting instead the “bloody” carnage of the birds they inevitably toss up in their ritual wake. Here is wit as Eliot styled it: “a recognition, implicit in the expression of every experience, of other kinds of experience which are possible.”

Marvell’s delirious loop de loop of cattle/spots/fleas/stars might unfold like a series of jokes, yet the stanza ricochets across modern American poetry. You hear echoes in Robinson Crusoe’s alienated displacement in Elizabeth Bishop’s “Crusoe in England”—“I’d think that if they were the size / I thought volcanoes should be, then I had / become a giant; / and if I had become a giant / I couldn’t bear to think what size / the goats and turtles were.” Or in James Merrill’s wry recasting of his life in The Changing Light at Sandover as a kitschy garden globe “rife / With Art Nouveau distortion / (Each other, clouds, and trees) . . . what was the sensation / When stars alone like bees / Crawled numbly over it?” And you especially rediscover Marvell in the distortions of Ashbery’s “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror”—“As Parmigianino did it, the right hand / Bigger than the head, thrust at the viewer / And swerving easily away.”

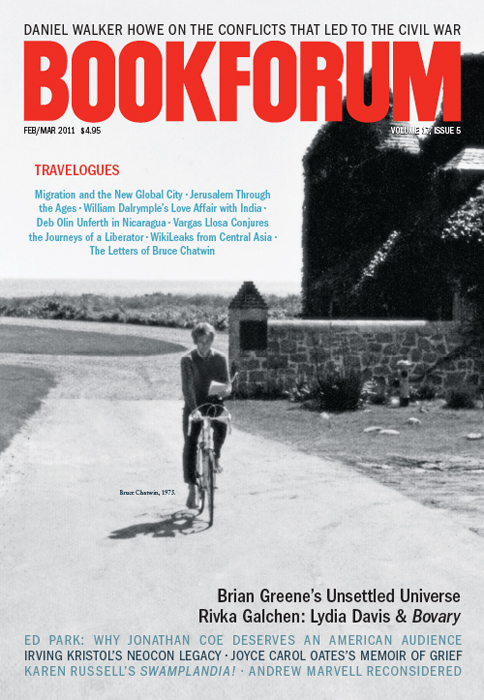

The other claim for Marvell in our moment is politics. Throughout The Chameleon, Smith insinuates “today’s world of shifting values and encroachments on personal and civil liberty” into Marvell’s mid-seventeenth-century vortex of civil wars, religious oppression, bank crises, mismanaged combat abroad, consuming conspiracies, racketeers, betrayals, and disillusion. (Beginning to sound familiar?) Born in East Yorkshire in 1621 and raised in Hull, he became financially precarious after the death of his minister father, when the poet was a scholarship student at Cambridge, working for board; most of his life, he tended to inhabit rented or borrowed rooms and supported himself as what Smith tags a “kind of educated servant”—tutor, secretary, or diplomat. During his stay at Appleton House, Marvell was about thirty years old and already had lived through the English Civil War, albeit mostly from the remove of the Continent, where he was amassing languages for future secretarial postings. He had seen the population of Hull drop by some 45 percent in the plagues of the 1630s. Over ensuing decades, he would march alongside Milton and Dryden in Cromwell’s funeral procession while working as one of the Latin secretaries to the Council of State, serve as the MP from Hull for almost two decades, disappear into Holland and Russia for months as a spy, and author anonymously (but hidden in plain sight—everyone knew) some of the most popular and corrosive prose satires in defense of religious tolerance and liberty—The Rehearsal Transpros’d, Mr. Smirke; or, the Divine in Mode, and An Account of the Growth of Popery and Arbitrary Government—as well as a Latin poem on the interrogation of a prisoner through torture.

The genius, then, of an extravaganza like “Upon Appleton House” is that it is a country-house poem that never lets you forget about civil war. Marvell won’t explicitly disclose that Lord Fairfax retreated to his rural seat after he resisted Cromwell’s orders to invade Scotland without provocation, but violence arises everywhere from his imagery—the playful “silken ensigns,” “fragrant volleys,” and “gentle forts” of Fairfax’s garden flowers, and, most powerfully, the careless savagery of the mowers: “These massacre the grass along . . . where . . . the plain / Lies quilted o’er with bodies slain.” Even that little farrago about the cattle, spots, fleas, and stars ends up as Marvell’s protest about how impossible it is for us to see and comprehend such civic horrors.

Operating at—as Smith suggests—the “meeting place of art, high politics and war,” Marvell clearly spooked his contemporaries. The seventeenth-century antiquary John Aubrey recalled that Marvell “was in his conversation very modest, and of very few words: and though he loved wine he would never drink hard in company, and was wont to say that, he would not play the good-fellow in any man’s company in whose hands he would not trust his life.”

A signature of Smith’s deftness in The Chameleon is that he rolls up barrels of documenting particulars without disturbing that core eeriness. If I possessed access to Mr. Peabody’s WABAC machine from Rocky and Bullwinkle, I’d love to know more about Marvell’s secret missions—as the duplicities and codes of espionage stalk the ambiguities in the poems. The poet as crafty chameleon in Smith’s smart and resonant readings is also the poet as skulking, threatened double agent. As Marvell wrote in a verse letter to the Cavalier poet Richard Lovelace, then imprisoned: “And as complexions alter with the climes, / Our wits have drawn th’infection of our times.”

Robert Polito’s most recent book is Hollywood & God (University of Chicago Press, 2009).