Decaying corpses, flayed limbs, home laboratories—Rebecca Messbarger’s new book, The Lady Anatomist, has all the makings of a horror story. Yet as Messbarger demonstrates, these grisly items were merely the tools of a nearly forgotten trade: anatomical wax modeling. In this study, Messbarger chronicles the rise of anatomical dissection and fabrication in eighteenth-century Bologna and charts the fortunes of one of its foremost practitioners, Anna Morandi Manzolini. Celebrated in her day, Morandi has since nearly disappeared from the historical record. Why did that happen, and what makes her worthy of rediscovery?

Messbarger pursues these questions through the book’s seven chapters, which survey both Bologna’s “traditional anatomical dissection scene” and the ways Morandi diverged from it. Before she and her husband, Giovanni Manzolini, began holding lessons in their household studio, the city was best known for its Public Anatomy: a pre-Lent amalgam of scholarly presentation and popular spectacle, including the ritual execution and dissection of criminals. Hoping to capitalize on this attraction, the pope founded a new Anatomy Museum, whose waxwork displays (dramatically posed écorchés [flayed men], a life-size replica of Adam and Eve) seemed hardly less sensational. By contrast, Messbarger argues, Morandi designed her anatomical facsimiles to educate, rather than awe or titillate. Equally adept as dissector, sculptor, and instructor, she lectured countless visitors at the couple’s home on their unparalleled collection of models (made by casting body parts in plaster, then filling the molds with hot wax). Long before receiving a university appointment, Morandi helped provide those “hard pressed to find similar instruction elsewhere” with an empirical understanding of the human body.

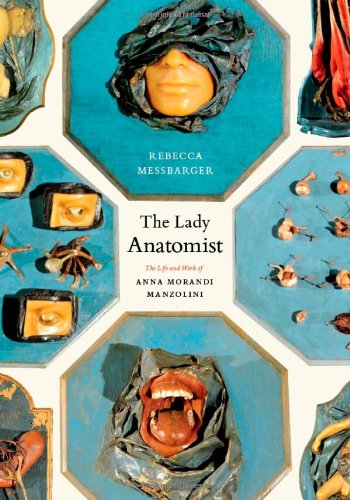

Her aesthetic contributions were equally important, as the book’s beautiful full-color reproductions of her work attest. Some of the most fascinating passages deal with the idiosyncrasies of Morandi’s style: her emphasis on “synecdochical” or “partial views” (a lone eye, a detached ear) rather than complete figures, and her unprecedented verisimilitude, which, as Messbarger argues, inspired both admiration and distrust. Indeed, gazing at Morandi’s “forcefully protruding tongues, grasping hands, and gaping eyes,” one experiences the “peculiar uneasiness” that Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset once attributed to wax figures: “Treat them as living beings, and they will sniggeringly reveal their waxen secret. Take them for dolls, and they seem to breathe in irritated protest.”

At times, Messbarger seems too invested in her image of Morandi as provocateur, fearlessly transgressing boundaries between “theory and practice, perception and cognition, science and art.” But such tactics are clearly meant to correct for the prevailing and, as Messbarger proves, unsubstantiated portrayal of Morandi as a mere improvvisatrice, or inspired dabbler, popularized by (male) biographers and competitors.

Messbarger, a professor of romance languages at Washington University in Saint Louis, has written previously on the role of women in Enlightenment Italy. Here, she draws on her deep knowledge of the period as well as on a rich trove of archival materials to make a strong case for her subject’s exceptional status as both artist and anatomist. The result is part biography, part feminist historiography. If her writing relies sometimes too heavily on academic tropes (hyphenated compounds like re-vision, frequent subheadings), her scholarly acumen also lends it uncommon authority.

She is particularly careful to avoid the “presentist” tendency to look at eighteenth-century phenomena through a twenty-first-century lens. Though, for the sake of lay readers, she might have alluded to at least one popular touchstone. I, for one, would have been interested to learn that Morandi’s death preceded by just a few years the debut of the world’s most famous wax modeler: Anna Marie Grosholtz, otherwise known as Madame Tussaud.