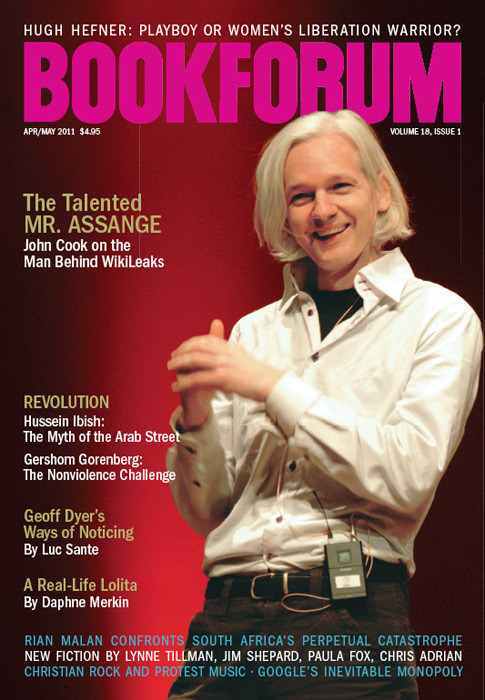

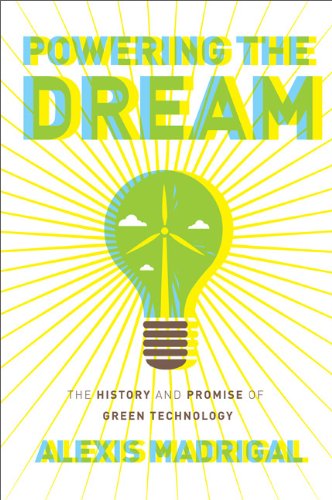

It’s almost impossible to write a book about our nation’s energy crisis that arouses in the reader any more excitement than what’s delivered in a maximum-strength barbiturate. I know this because I recently published one such book and found myself going out of my way, in my reporting rounds, to pursue the most extreme kind of high jinks—choppering out to ultra-deep oil rigs, spelunking into the Manhattan electric grid, even infiltrating a boob-job operation—all in the service of sustaining reader interest. While Powering the Dream: The History and Promise of Green Technology may sound like a snoozefest, Alexis Madrigal manages—without any gonzo shenanigans—to engage and sometimes even electrify the reader with lean and jaunty prose, skillful storytelling, analytic theorizing, and a proficiency in factual gee-whizzery.

Madrigal sets out to chronicle the surprisingly deep and colorful history of renewable energy in America—which stretches back (who knew?) to the days when there were Whigs in the White House—in a string of vignettes recounting the trials of the unsung inventors who foresaw our current industrial crises and tried to preempt them even 180 years ago. We learn of John Etzler, for instance, a futurist and engineer who, in the 1830s, saw “industrialism [as] a vicious energy monopoly” and wrote that power from the sun, wind, and waves would be “more than sufficient to produce a total revolution of the human race.”

We also encounter the electric taxi cabs developed by Pedro Salom and Henry Morris, which came to dominate Manhattan’s streets in the 1890s. We hear the forgotten story of William J. Bailey, who pioneered the Day and Night Solar Heater company in the 1920s and sold hundreds of thousands of solar-thermal units before natural gas became the industry standard. And we read about scientist Jeff Johnson, who spent years wading knee-deep in pond scum, collecting thousands of rare species of algae for synthetic-fuel development in the 1970s, only to have his collection “lost” by the Reagan administration’s Department of Energy.

The reason these would-be heroes are unknown is obvious: Their theories and innovations failed. Some bombed publicly, others fizzled quietly, but all have since been chucked into the dustbin of history and forgotten along with millions of other technological duds. As engaging as these individual portraits are, though, it’s hard to avoid the suspicion that they add up to less than the sum of their parts. Who really benefits from reading story after story about history’s green-tech losers? Why excavate them?

No clear answer emerges in Powering the Dream, though Madrigal does try to tamp down these suspicions by making the case that past is prologue and that these stories of failure can be instructive: “The bottom line is that [until recently] we’ve missed chances to have a cleaner energy system, and if we don’t heed the lessons of the past, we could blow this opportunity, too.”

But what lessons do we really learn? We learn that power began as a distributed resource, only to be centralized over the course of the twentieth century. We are reminded that Americans witnessed one complete overhaul of the country’s transportation system—from rail to roadways—and that we’re primed again for such a bold transformation. We learn that most green technologies didn’t die out for reasons of cost alone; political factors were just as influential. And yet the many lessons that Madrigal offers don’t cohere around a central thesis.

Powering the Dream is nevertheless fascinating in the context of today’s nascent rebirth of green technology. Billions of dollars of public and private dollars are pouring into the very areas of innovation that failed so long ago—start-ups developing solar, wind, and geothermal power, electric cars, smart-grid components, algae fuels, and power storage. But green technologies are only beginning to catch fire—Madrigal doesn’t convince us that they won’t inherit the hapless fate of their failed antecedents.

Madrigal briefly explores China’s emergence as the green giant of clean-energy investment—last year it spent $250 billion on green R&D, double what the United States did—which makes our nation’s early, failed attempts at pioneering these industries all the more humiliating. He mentions in passing that solar-thermal technology has gained a solid foothold in China, which has recently marketed millions of water heaters just like those Day and Night Solar Heater units of 1920s vintage. But he neglects to tell perhaps the best clean-energy comeback story of our day: Those electric cars that proliferated on the streets of Manhattan and then died in the early part of the twentieth century are experiencing a spectacular resurgence. In February, China announced plans to manufacture one million electric cars annually—more than the total number of Toyota Priuses sold worldwide in the past decade.

Madrigal is at his best when he teases out the larger theoretical framework for his investigation into the origins and future of green technology. Environmentalist thinkers have long held that green technologies possess a kind of utopian promise—the notion that, as Madrigal describes it, “these technologies can be utilized to advance humanity to a new level of wholeness.” The dream has long been to develop what Madrigal calls “the perfect power,” an unlimited, democratic, and clean source of electricity for all global populations. And in line with the general drift of this thinking, he posits that renewable energy could help promote heightened social awareness throughout the world.

Even if Madrigal doesn’t wind up convincing us that these technologies will succeed in any significant way, his contagious enthusiasm for them makes us want them to. He makes the dream of a perfect power source seem all the more urgent, now that we know for how long, and in how many past episodes, it’s been deferred.

Amanda Little is the author of Power Trip: The Story of America’s Love Affair with Energy (Harper, 2009). Her articles on energy and the environment have appeared in Vanity Fair, Wired, and the New York Times Magazine.