Spare a thought for poor Susie Breitbart. On January 17, 1998, her husband, conservative Web publisher Andrew Breitbart, got home “around midnight,” went online (which took some time in those days), and eventually (with, he writes, an actual tear rolling down his cheek) turned in bed to his presumably sleeping wife and said, “Susie, history just happened . . . Drudge just changed everything.”

On September 20, 2001, Breitbart took his family to watch an antiwar demonstration. “I remember looking at Susie and saying, ‘This is going to be the resurgence of the silver-ponytailed professoriate and the Baby Boomer left. This is what they’ve been waiting for. This is going to be their last stand to fulfill their self-appointed 1960s mission.'”

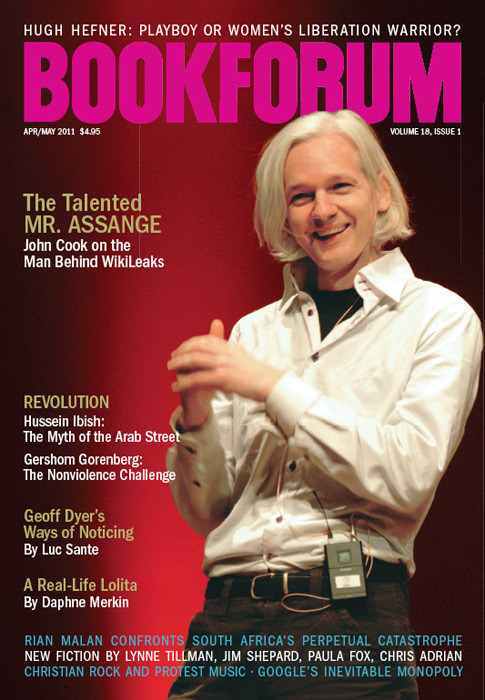

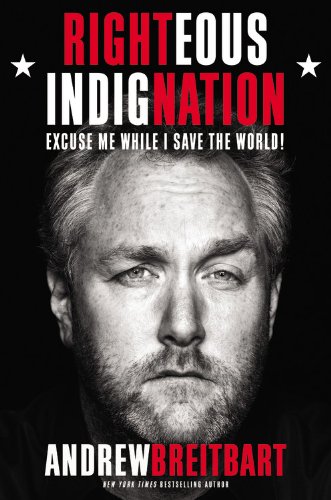

Politics is always on the menu now in the Breitbart household. “My wife married an almost inappropriately always-lighthearted guy fourteen years ago,” he writes near the end of Righteous Indignation, his memoir and manifesto. “Now she wakes up next to a firebrand who is one of the most polarizing figures in the country.” The book is the story of that transformation—from fun, funny guy to obsessive bore—disguised as a traditional “How I saw the light and became a conservative” tale. For good measure, Breitbart throws in a contemporary Tea Party twist by including a bizarre retelling of selected portions of American history and a couple of recycled “Rules for Radicals,” cribbed from community organizer Saul Alinksy, who exerts a curiously Rasputin-like hold on the imagination of the postmodern conservative.

The villain of the book is a Borg-like formation of leftist cultural consensus that Breitbart calls “The Complex.” It’s compared to the Matrix. It tears down decent men like George W. Bush. It ignores thuggery and criminality in Democratic presidential administrations. It tries to give Focus on the Family impresario Gary Bauer, a short-lived 2000 GOP presidential candidate, the flu.

Much of Righteous Indignation, true to its name, is taken up with Breitbart’s hatred of the Complex, the all-powerful hegemonic force that encompasses the press, the Democratic Party, and the entertainment industry. (Breitbart actually paraphrases Adorno on how the culture industry dictates desires to the masses but never lets on that he’s essentially borrowed the critique.) Yet the book also showcases Breitbart’s desperate need for attention from the mainstream press and his pathological need to be liked by celebrities. (Susie’s father, actor and game-show panelist Orson Bean, introduced a skeptical Breitbart to the written work of Rush Limbaugh. “This guy had appeared on the Tonight Show couch seventhmost of any guest,” Breitbart recalls thinking. “His opinion mattered to me.”)

Then again, the media-deriding impulses of the right have always exhibited a parasitic relationship with the media mainstream. Drudge relies on the Complex to perform all the actual reporting that’s published on his site, and the mainstream press has been licking his boots since the late 1990s. Until Breitbart began rotating in original content from his “Big” sites—Big Journalism, Big Hollywood, Big Government, and the like—his breitbart.tv primarily hosted wire-service copy and mainstream news videos. He makes a point of noting every time Jon Stewart says something complimentary about his work.

Based on the testimony here, it’s hard not to conclude that Breitbart imagines such sinister collusion among Democrats, left-wing activists, and the press because he has operated his own version of the same scandal-making machinery on the professional right. He teased his famous ACORN story—the misleadingly edited gotcha videos produced by conservative college activist James O’Keefe purporting to show community organizers in ACORN offices advising clients on how to conceal criminal conduct—in his Washington Times column. He then simply handed the first tape directly to Fox News, where it aired the following morning. He gave a later tape to the News Corporation–owned New York Post, and it made the front page. O’Keefe was trained at the Leadership Institute, the nonprofit responsible for Grover Norquist and Karl Rove. Breitbart himself attended conservative finishing school at the Claremont Institute, alma mater of frequent Senate candidate Christine O’Donnell and influential right-wing blogger John Hinderaker.

The book includes a call for contributors to join Breitbart’s growing stable of news sites, a defense of the nonracism of the Tea Party, a brief disquisition on the villainy of Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, and a lengthy account of the time Breitbart was booked, then axed from, an ABC News broadcast. Missing is any defense of conservative policy, beyond some halfhearted maxims about the free market. This is because Breitbart scarcely has political beliefs. He is in it for the battle.

And now, having destroyed ACORN, he sets his sights on Martin Sheen. “Hollywood is more important than Washington,” he says—which makes sense for a man whose politics are purely tribal and completely disconnected from any opinion about optimal public policy. So he and his friends, having constructed an alternate media, will now construct an alternate Hollywood—an entertainment industry where, for once, militarism, nationalism, and simplistic binary moralism will be celebrated. No more cocktail parties. Which raises a delicate conundrum: Since Breitbart, by his own confession, was immune to the “cultural Marxism” of his college years at Tulane thanks primarily to his constant inebriation, what’s to stop the future products of Breitbart-led Big Hollywood from sleeping through their conservative indoctrination in Big Academia and stumbling, as adults, into rebellious liberalism? I wouldn’t be surprised if, when a Breitbart heir brings home a romantic interest in this glorious new future, Susie slips her a samizdat copy of Rush Limbaugh Is a Big Fat Idiot.

Alex Pareene is a senior writer for Salon.