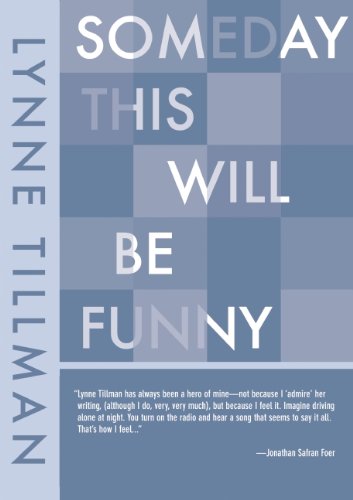

Lynne Tillman’s characters inhabit language the way others live in rooms and cities. It’s not that they are made only of words—all literary characters are—or that they don’t have their own versions of material longings, needs, attachments, and obstructions. What’s different is that they are attuned to language. They fraternize with words even when they are not talking. They treasure clichés and ready-made phrases as if they were messages or hints, turning them over to find their wisdom, or at least the joke wrapped inside them. In her collection This Is Not It (2002), when a woman makes a “last-minute decision,” she very soon wonders what a “first-minute decision” would look like. There is an echo of this thought in Tillman’s new story collection, Someday This Will Be Funny: “The decisive moment was an indecisive one for her.” We instantly start adding up our own moments of that sort, finding far too many.

Words, for these characters, provide a way to question the world while taking part in it, to interrogate the forces of family, history, even language itself. “Like sin,” we read in one of Tillman’s earlier stories, “one’s own history is not original, but it weighs heavy.” Yet another character tells us she has “invented an epic, The Lost City of Words.” She says that “it’s unwritten like the journal I don’t keep” and that the title “ensnares and encircles everything I can’t find words for.” In Tillman’s hands, even this lost place has an elegant and ironic verbal life; ensnaring and encircling everything is far from being nothing.

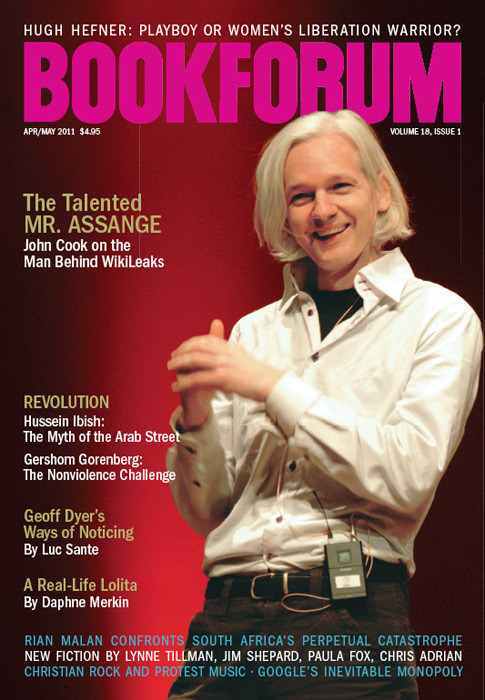

Tillman is the author of four volumes of stories, including the new one, and five novels, which include Haunted Houses (1987), No Lease on Life (1998), and American Genius, a Comedy (2006). Her works often have a relation to the visual arts, but not because of any obvious visual effects in them. They use words, rather, to construct a take on the world the way a painting or an installation might, and she herself speaks of “writing fiction as an analogue to art.” The result makes us think, but it also makes us just pause and wonder and remember, the way we do with art we like but don’t want to (or can’t) reduce to mere meaning.

One of Tillman’s most edgy and engaging characters is called Madame Realism, a decidedly original art critic whose humorous monologues dwell on language, sex, and sound bites from her subconscious. We meet her in six stories in This Is Not It, and once again in Someday This Will Be Funny. In the new book, she worries about power and haunts the social occasions of presidents and their wives, whispering to Laura Bush, resurrecting Lincoln, quoting Eisenhower—“Things are more like they are now than they ever were before”—and making epigrams: “You never get a second chance to make a first impression.” In an older piece, we find her waking up in the morning, taking a little tour of her mind, and finding she has turned into the catalogue of an exhibition: “There were numbers and letters next to some of her paragraphs which referred to artwork that might hang on walls or sit inside plastic boxes on platforms.” She finds the change pleasurable but worries that she may be losing some of her ambiguity, becoming too fixed and linear. But then her paragraphs shift—“dates, places and names jiggled about as if an acrobat were upsetting and resetting her type and throwing it into the air”—and her optimism returns. Was this a dream? Probably, but Tillman herself wouldn’t want to shed ambiguity altogether. “No longer a catalogue,” she writes of Madame Realism, “if she had ever been one.” Elsewhere, Madame Realism visits the Normandy beaches and reflects on war and death. We can’t lose the past, she thinks, “though we are, in a sense, lost to it or lost in it. . . . Madame Realism was astonished to be in a ghost story, spirited by dead men.”

Tillman wants us to think about the world as it is, but without preconceptions—it’s amazing how unrealistic the real can seem if we can manage this. Her character’s name suggests several possibilities. It is a nickname given to a person who in all her quirkiness believes she knows the score, and even what the game is. It describes an allegorical identity, belonging either to an actual imagined person or to a more abstract figment, like Miss Manners or Mister Nice Guy. And most elusively, it evokes a mode of the imagination, and an ancient and continuing preoccupation with the real as the mind can know it, and embodies a rebuke to the many current forms of rabid fantasy that go around calling themselves realism. Madame Realism herself asks rhetorically if she “doesn’t . . . exist, like a shadow, in the interstices of argument.”

For all their attention to ambiguity, Tillman’s stories make impressions almost immediately. The titles of Someday This Will Be Funny themselves tell great stories: “That’s How Wrong My Love Is,” “The Unconscious Is Also Ridiculous,” “But There’s a Family Resemblance,” “Save Me from the Pious and the Vengeful.” Some pieces feature inspired renditions of figures from pop culture and history, with characters including Clarence Thomas, Marvin Gaye, and John Lennon, all of whom are caught up in the intelligent melancholy that marks the rest of Tillman’s work. Other characters, named or not, remember old affairs, long for new ones, talk to their analysts, wonder about acts of so-called kindness, stay married in spite of (real or imagined) infidelities. They drink, make jokes, sometimes confront awkward truths, more often devise brilliant evasions of them. Quite often they write, clinging to sentences as if to memories or old friends. They possess an urban, therapized sensibility; they know that “all bearers of wishes and jokes are also serious,” and they know when an analyst is “not silent enough”—although they are too discreet to tell us what he said. Of several of them it might be noted, as it is of one skillfully dissatisfied woman, that “adolescence malingered in every cell of her mature body.” Nothing like youth to keep you young, although who can tell if this is a good thing.

None of these people is really desperate, though. Unsettled, out of focus, perhaps, but always alert and ready to dissect another disappointment. Tillman generously lends many of them large portions of her own wit. “No one lives in the present except amnesiacs,” one of them thinks. Faces can be lifted, and are, a character notes, “but some things can’t be lifted.” In the novella “Love Sentence,” the aptly named Paige Turner thinks that “writing might be an act of love, a kind of love affair, or a way of loving. . . . Always wanting, writing exposed its own neediness, like unrequited love, which might be the same thing, she wasn’t sure.” Paige is also the person who offers this impeccable definition of a broken heart: “My heart broke before I even thought about love. It broke when I wanted something and couldn’t have it, and I don’t even remember when or what that was.”

But then Paige can write that “love dissolves disbelief, since it defies credulity,” and the more we read her the more she sounds like the narrator of the very last story in this volume, who eloquently recalls and rewrites several paragraphs from “Come and Go,” the opening piece in This Is Not It: “Out of nothing comes language and out of language comes nothing and everything. I know there will be stories. Certainly, there will always be stories.” It would be a mistake, I think, to read these three sentences as the simple affirmation of a conviction or the simple expression of a hope, or to read them ironically, as if they just don’t believe what they say. Stories are not nothing, and they are not everything, either; and language does many things beside telling stories—it can make stories impossible, for example, by banning them or stealing their words from them. There will always be stories, the narrator is right. But will there always be someone as fast and subtle and kindly as Lynne Tillman to tell them?

Michael Wood is the author of numerous books, including Literature and the Taste of Knowledge (Cambridge, 2005). He teaches at Princeton University.