In 2004, Francisco Goldman fell in love with Aura Estrada, a writer and graduate student from Mexico City who was working on a Ph.D. at Columbia University. At the time, he was writing a dark, violent book, The Art of Political Murder, a nonfiction account of the assassination of Catholic bishop Juan José Gerardi Conedera by the Guatemalan military and of the atrocities perpetrated against the country’s Mayan population. But the younger Aura brought joy into his life. The two married in 2005. In 2007, only months after he finished his book, Aura died in a bodysurfing accident in Mazunte, on the Pacific coast of Mexico. Say Her Name, Goldman’s latest book and fourth novel, is constructed out of the raw grief he experienced following his wife’s death.

Goldman, also a journalist for the New Yorker and Harper’s, has called his earlier novels “complex narratives about the relationship of storytelling to history—tragic history.” In his autobiographical first novel, The Long Night of White Chickens (1992), a man investigates the murder of a Guatemalan woman who lived with his family when he was growing up. The Divine Husband (2004) invents an episode in the life of the Cuban poet and freedom fighter José Martí. Goldman bases his latest fiction on fact as well, using his name and Aura’s throughout. But the resulting elegy isn’t about “tragic history” so much as personal tragedy.

He opens simply: “Aura died on July 25, 2007. . . . Three months before she died, April 24, Aura had turned thirty. We’d been married twenty-six days shy of two years.” But soon, Say Her Name builds into an invocation of his own Eurydice, taken from his side in the first flush of marriage. “Descending into memory like Orpheus to bring Aura out alive for a moment, that’s the desperate purpose of all these futile little rites and re-enactments,” he writes.

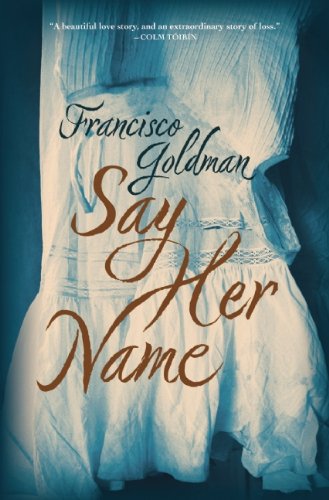

Returning to the apartment he and Aura shared in Brooklyn six weeks after her death was “like stepping into an absolute emptiness.” Two of her girlfriends create an altar around the bedroom’s floor-to-ceiling mirror, with its centerpiece her wedding dress, a “minimalist version of a Mexican country girl’s dress, made of fine white cotton.” The image of Aura’s dress presides over the widower’s solitary bedroom and hovers over the novel. In a wry aside—which offsets the looming risk of sentimentality—Francisco thinks about what his “guy friends” would have done had they been there. They’d likely have said, “Let’s go to a bar.”

In other recent additions to the literature of grief, Joan Didion and Joyce Carol Oates have confronted the problem of how to write about so emotionally overdetermined a subject as death, particularly the death of a loved one. Both turned to memoir. Goldman’s choice to fictionalize his story frees him from facts and lends him aesthetic distance. He doesn’t, like Didion and Oates, analyze the experience of grief—rather, he lets his fictional double inhabit it. Fiction allows him to throw his voice and thereby to mourn without becoming maudlin.

The drama accumulates. Francisco worries that in the process of mourning, in the process of writing, he’ll become detached; that, like Orpheus, he’ll glance back at his dead wife and lose her forever. Additional tension arrives in the form of Aura’s ferociously protective mother, Juanita, who cut off all contact with Francisco after her daughter died. She evicts Francisco from Aura’s Mexico City apartment and prevents him from possessing even a small portion of her ashes. “Juanita had Aura’s ashes. I had Aura’s diaries,” he writes.

The diaries prove useful. With them, Francisco, much like a fiction writer, speculates about the secret world mother and daughter shared and reconstructs Aura’s childhood. He learns to forgive Juanita, and finds a more reportorial tone as he retraces Aura’s final days. In a medieval church he lights a candle, prays to the Virgin to take care of Aura, and mocks himself for doing so. This mix of religious devotion and undercutting voice keeps the author safe from pathos as he homes in on the revelation that will release Francisco from his widower’s bedroom with the floating white dress. But even with this freedom, Say Her Name makes one thing clear: In the imagination, Francisco’s love never dies.