I am not the sort of person who would ordinarily elect to dine at Grant Achatz’s radical Chicago restaurant Alinea, which features “mischievous science-project cooking,” as New York Times restaurant critic Sam Sifton recently described it. I am generally put off by meals that are as much pyrotechnics as pleasure. I am not interested in dried crème brûlée, which appeared on Achatz’s first menu, and I find his description of angelica branches filled with apple puree—one element of the twenty-six-course dinner he prepared for a former Chicago Tribune food writer and his friend—more obnoxious, not to mention exhausting, than enticing:

Historically, the plant’s hollow stems had been used as straws for cocktails, perfuming the beverage with their celery-like aroma. So it seemed natural to honor that tradition and have Bill slurp something through the cleaned-up branches. I began removing the plants from the jug with the intent of snipping away the leaves and paring them down to a single straw, when I stopped. They looked like flowers in a vase, they were alive, and they were a part of that small farm in Michigan. We needed to serve them that way. In fact, that needed to be the entire point of the course. After a brief description from the maître d’ Chris Gerber, my go-to front-of-house guy, I wanted Bill and David to remove the branches from the glass vase that we would serve them in, contemplate the angelica, its history in gastronomy, and hear about Kate and her tiny farm five hours away. What I put inside for them to eat was almost irrelevant.

I don’t want to be told what I’m supposed to experience; I want to eat. Isn’t that the entire point, or at least the larger part of it? I may, in fact, be one of the very people Achatz readily acknowledges who look at his food and think, “It’s bullshit.”

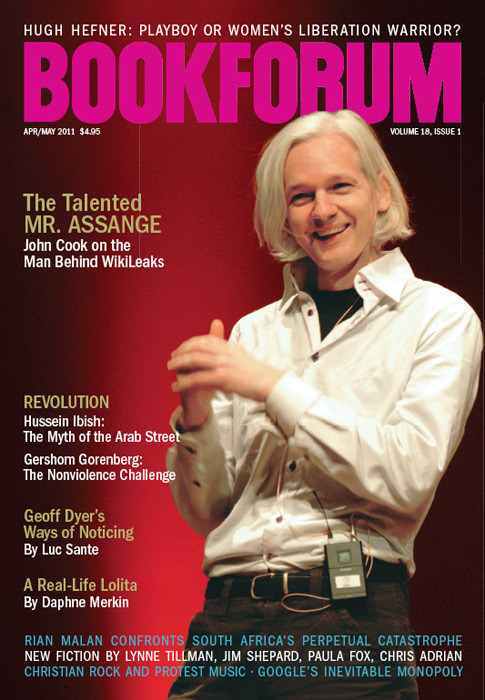

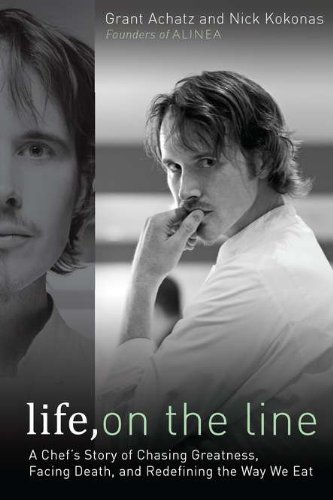

Yet here’s the thing: After reading Achatz’s memoir, Life, on the Line: A Chef’s Story of Chasing Greatness, Facing Death, and Redefining the Way We Eat (Gotham, $27.50), I like him. And because of that, I would now be more inclined to eat something that arrived at the table surrounded by smoldering oak leaves (in Achatz’s case, a pheasant-breast dish designed to evoke the Midwest in autumn) than I would have been before. In his book, written rather awkwardly in alternating sections with his business partner, Nick Kokonas, Achatz says truly ridiculous things like “We began to realize that the plates, bowls and silverware that had been used to consume food for hundreds or thousands of years did not work optimally for the food we were now creating.” But these pretensions are often eclipsed by his appealing albeit nerdy enthusiasm for things like serving squid in various textural preparations to highlight “the different mouthfeels that could be achieved with a single protein.”

All this fancifying is a far cry from the cooking Achatz grew up with. His parents owned a humbler, yet successful, restaurant in small-town Michigan, where he learned to flip eggs and to butter toast expertly. He knew early on that he wanted to cook, and headed to the Culinary Institute of America in the winter of 1993, at the age of eighteen. From there, as the ’90s unfurled, he embarked on a series of dream jobs, which it seems he got simply by writing to his favorite chefs with such passion that they invited him to try out in their kitchens, whereupon he proceeded to wow them with his hard work and vision. Before the age of thirty, he had not only had the guts to quit on Charlie Trotter, one of the great pioneers of fresh, imaginative fine dining, whose egotism repulsed him, but also worked at the legendary French Laundry under Thomas Keller and, after a three-day inspirational pit stop at Ferran Adrià’s elBulli arranged by Keller, departed in 2001 to take over the kitchen at a failing restaurant called Trio in a Chicago suburb.

For most people, going from Napa to Evanston would be a comedown, but for Achatz it was like passing into the promised land. Soon thereafter, just past his thirtieth birthday, he launched Alinea in Lincoln Park, to overblown fanfare—it was hailed as “best new restaurant in the country” by Food & Wine two months before it had even opened. Regardless of whether you’re intrigued or irritated by the idea of a bittersweet-chocolate foie-gras lozenge on a stick, it’s impossible not to be a little in awe of Achatz’s drive to succeed entirely on his own terms. Even after nearly two years of attention and praise from the time of his opening (including Alinea being named the number one restaurant in America by no less than Ruth Reichl in Gourmet), Achatz can’t help himself: “All of my life I was surrounded by success,” he writes. “My parents owned their own restaurant before they were thirty years old. . . . I watched Thomas [Keller] grow into an international culinary giant who will undoubtedly be heralded as one of the greatest American chefs ever. The whole time I wanted to be as good as all of them. I knew the only way to come close was to do something different; otherwise, I would always be in their shadows.”

As for how he makes the molecular-gastronomic magic that became his “something different” happen, Achatz is charmingly unsure, and the parts of his book in which he describes his creative process are oblique, to say the least. In one instance, seventeen hours into a miserable, grueling workday at Alinea, he pauses for a moment and kismet strikes: “I started to recall the day and where we went wrong, I remembered the wineglasses breaking and I smelled raspberries. And just like that it happens. Raspberries that are fragile like fine glassware, maybe even clear like stained glass. They smelled like roses, so we’ll pair them with roses. I walked back into the kitchen, pulled the tray of raspberries from the cooler, and looked at them. ‘How the hell do I do that?’ I thought to myself.” Before you know it, he’s breaking out the pectins and going to town.

But all is not rosy gelatin in Achatz’s world. There are his two young sons—one named Keller, after his mentor—whom he doesn’t see enough, the product of a troubled relationship that turns, briefly, into a misbegotten marriage. And then there is the blow of mythic proportions dealt to him when, just as Alinea is getting into the swing of things and Achatz has fallen newly in love, he learns that he has advanced squamous-cell carcinoma, a skin cancer, in his tongue. The scene in which the Alinea staff gather around a speaker phone to hear this announcement from New York, where he’s headed to Sloan-Kettering, is devastating, as is the recommended treatment: “I had been given a clear directive: Cut out your tongue as soon as possible.” But Achatz being Achatz, he can’t do things other people’s way. Despite the fact that he’s unable to taste anything or even eat, he decides he’d rather die than take the doctors’ advice. “The quality of life seemed low at best, while the odds of dying anyway were very high . . . it was unlikely that I could be a great chef. . . . I didn’t want to live without my identity. And I didn’t have the energy or desire to create a new Grant Achatz.”

Salvation arrives when news of his illness hits the Tribune (no one can resist a story about a famous chef stricken in the very organ he uses to make his living), and a doctor in charge of a successful clinical trial at the University of Chicago reads the article, calls the restaurant and upon examining Achatz tells him he has a shot not only at living but at keeping his tongue, too. Achatz enters the trial, responds to the chemotherapy and radiation immediately, and endures the ravages of treatment in the form of balding, rashes, weight loss, and cracking skin, followed by surgery on his lymph nodes. All the while, he works fourteen-hour days at Alinea, where his staff shave their heads in solidarity, in order to keep his sanity.

His survival is a foregone conclusion. But recovering from cancer is the least interesting part of Achatz’s story thus far, if only because unlike everything else, it’s not of his own making. For the first time in his life, he is forced to rely entirely on someone else’s vision—not to mention an awful lot of luck—and his only role is to marvel and be grateful. Which, fortunately, he does. Once in remission, he spends more time with his kids and dives into his restaurant (and a new one, Next, featuring a new cuisine and time period every three months, with Aviary, an adjacent cocktail lounge; both are slated to open in Chicago April 1).

As a young boy assigned to the role of chief egg cracker at his grandmother’s egg station at the diner, Achatz had to work his way up from the “over-hard” eggs, which could withstand a broken yolk. Now, it’s not difficult to imagine that as he goes forward, he’s carrying with him the same feeling of accomplishment he had when he arrived at that earlier, no less epic pinnacle. “A bit of pride welled up in me. I was the little kid who could cook—I was at the top of the egg-station now, doing the over-easies.”