In 1999, Woodstock’s thirtieth-anniversary festival ended in a wave of sexual assaults, rioting, and fires—an unlikely celebration of the original Woodstock’s “three days of peace and music.” The breed of angry male bands that dominated the festival and the airwaves that year with juvenile sexist resentment (as summed up by Limp Bizkit’s summer hit, “Nookie”) was a reminder that rock’s rebellion is often unfriendly to women. After Limp Bizkit’s inane and sloppy set (during which a gang rape allegedly occurred in the crowd), Rage Against the Machine, a precise and polished band—perhaps the most radical and influential protest group of its generation—took the stage. But the audience barely registered the difference. Rage’s song about racist police violence, “Killing in the Name,” combines pointed and articulate lyrics (“Some of those that work forces / Are the same that burn crosses”) with a brilliant and simple catchall of resistance: “Fuck you, I won’t do what you tell me.” The crowd of nearly two hundred thousand raucously took up this chant with front man Zack de la Rocha, as the band burned an American flag onstage—a gesture recalling the defiant spirit of Woodstock counterculture in an otherwise disastrous and largely apolitical weekend.

In 33 Revolutions Per Minute, British rock critic Dorian Lynskey calls “Killing in the Name” “the perfect gateway-drug protest song, channeling the boiling frustration of a thwarted teenager in a sociopolitical direction,” but the spree of unfocused aggression at Woodstock ’99 demonstrates how easily rage can be detached from ideological moorings. Preaching beyond the choir is almost always achieved at some cost to the message, because, as de la Rocha says, “we’re dealing with this huge, monstrous pop culture that has a tendency to suck everything that is culturally resistant into it in order to commodify it.”

Lynskey divides his survey of protest music into thirty-three chapters, each named for a song that encapsulates a cultural movement or a flare of political resistance, in genres including Motown, punk, and rap, among others. (Full disclosure: Lynskey mentions my band Le Tigre in passing.) In one of the book’s best chapters, departing from conventional notions of protest in pop music, Lynskey admits disco as a special case, focusing on the genre’s “hidden politics.” He cites Carl Bean’s 1977 gay dance hit, “I Was Born This Way,” noting that its activist lyrics (including “Yes, I’m gay”) were atypical of the hedonistic scene: In early disco, protest was the subtext of pleasure, understandable in its original context of largely black, gay clubs. Disco was “political by its very existence: an exuberant response to hard times, spearheaded by marginalized cultural groups,” Lynskey explains, and its mandate to leave the dance groove unburdened left political content unelaborated in the sweaty knowingness of gay nightlife.

When the genre entered the mainstream, politics went undercover. Former Black Panther Nile Rodgers, a member of the disco supergroup Chic, is both proud of and rueful about the band’s strategy of oblique reference and double meaning, which, Lynskey says, “smuggled social comment onto the dancefloor.” The 1979 song “Good Times” slickly parodied “faintly ludicrous high-life aspirations” during a crushing recession, but many listeners took the song as an escapist inducement to keep on partying. Rodgers astutely counters this misreading, noting that fans did not expect allusive lyrics (such as the line “Happy days are here again,” a reference to a Tin Pan Alley song played during FDR’s Depression-era presidential campaign) from black disco artists, but “if Dylan was standing in front of a tank singing ‘happy days are here again,’ people would say, ‘oh check Bob.’”

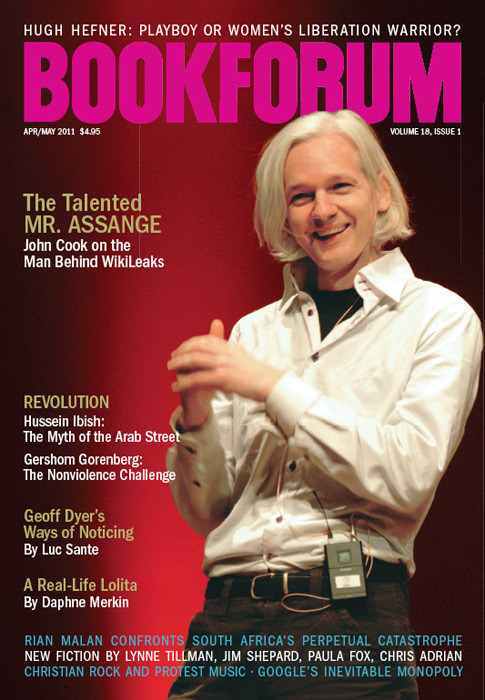

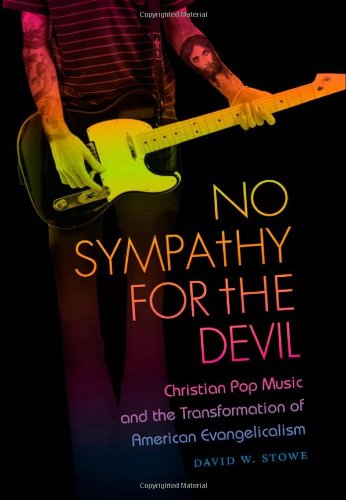

Reading Lynskey’s account of protest music’s heyday in the 1960s, it’s clear that his preferred brand of progressive idealism will soon peak and then fade from the scene. What he doesn’t tell us is that the real success story of political pop in recent history is the saga of Christian rock, a genre that originated in ’60s counterculture, filtered into the mainstream, and was co-opted by conservatives. In No Sympathy for the Devil, author David Stowe quotes an interview with Hollywood pastor Don Williams from the Christian magazine Guideposts: “Look at the mob that went to Woodstock. Jesus wasn’t there. The kids spent a week getting stoned and smashed and pregnant. I feel that love died at Woodstock for the kids who were there. I doubt that rock could ever pull off another Woodstock. But rock-gospel could. And Jesus would be there.”

Stowe follows Christian pop music as it evolves from sound-tracking the left-leaning countercultural Jesus movement, with its saucer-eyed teen burnouts baptized in the surf of ’60s Corona del Mar, California, to mobilizing Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority and the Reagan Revolution. Stowe’s narrative shares themes with Lynskey’s: Both authors recount the dilemmas of songwriters tightening—and often losing—their grasp on their message as they chase or abdicate fame. And Dylan is, of course, a star of both books.

Stowe finds the roots of Dylan’s 1978 conversion to evangelical Christianity in his turn to conservative family values as early as 1966. The sexual mores of Woodstock Nation, which, Dylan complained, “seemed to have something to do with me,” were, to him, “the sum total of all this bullshit.” Meanwhile, he embraced Christian music’s traditional themes, and he performed with a missionary’s zeal for the music’s proper reception. Trailblazing long-haired Christian rocker Larry Norman watched Dylan during a postconversion performance and observed that he was “kicked around” by skeptical Christians, while fans who came to hear his godless oldies booed him. Dylan taunted them: “I said the answer was ‘Blowing in the Wind,’ and it was. I’m telling you now Jesus is coming back and He is!”

Norman had his own ambivalent relationship with pop-music success, beginning with his experience a decade earlier with the band People!, a one-hit wonder that charted with a cover of the Zombies’ “I Love You” and opened for acts like the Jimi Hendrix Experience and the Doors. People! primarily played songs about girls, but the tune “We Need a Whole Lot More of Jesus (and a Lot Less Rock and Roll),” Norman’s choice for the album’s title track, was a clear exception. Norman quit People! on the album’s 1968 release date, because Capitol insisted on calling the record I Love You. For a time, he struggled as a destitute street evangelist on Hollywood Boulevard.

Norman would later restart his pop career writing musicals, but it was Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice’s secular 1971 Broadway musical Jesus Christ Superstar that captured the imaginations of many Christians, in part, Stowe suggests, by recasting Jesus as a Dylan figure: “young, shaggy, given to esoteric sayings and cryptic outbursts, unmistakably Jewish and sympathetic to the downtrodden.” The musical was the subject of much grassroots piracy by church theater troupes and summer camps (among other groups), and Stowe argues that these DIY productions were an example of the movement’s strategy to win Christian youth with savvy appropriations of mass culture.

As Christian pop evolved with folk artists like Randy Stonehill, ’70s stars such as Children of the Day, and gospel rockers Andraé Crouch and the Disciples, it did not rely on the force of its message alone to reach potential converts. Evangelists were on the ground and on the air, selling a lifestyle package of salvation that, by the 1980s, came with voter guides. Stowe concludes that Christian pop was an instrumental force in Reagan’s election and helped a generation of evangelicals “create a political style and voting coalition that has shaped national ideology . . . even into the era of Obama.”

In contrast to Stowe’s upbeat tone, Lynskey wonders whether he has “composed a eulogy” with his survey of political pop, writing in his conclusion that “the failure of protest songs to catch light during the Bush years leaves one wondering what exactly it would take to spark a genuine resurgence.” Such ruminations strike a note of nostalgia for a mythical, lost golden era and make a claim about the extra-market power of pop music that’s hard to believe in. Yet I sympathize with Lynskey—it is frustrating to realize that the Christian Right has proved to be the movement most successful at using music to consolidate political power. However uncomfortable it is for secular dissenters to take a page from evangelical pop, the Christian faithful have no such qualms about harnessing the devil’s music, with startling success. As the rise of Christian rock demonstrates, culture wars are mercilessly fought, and won—to quote a young Dylan—“when God’s on your side.”

Johanna Fateman is a writer, artist, and musician living in New York, where she owns Seagull Salon. A DVD of her band Le Tigre on tour will be released later this year.