“Politicians, ugly buildings, and whores all get respectable if they last long enough.” So said malevolent tycoon Noah Cross to Jake Gittes, the gullible gumshoe in Roman Polanski’s Chinatown, a dark hymn to Americans’ limitless capacity for self-delusion in the face of power. Lately, Polanski must be wondering how his old pal Hugh Hefner has managed—with a history scarcely less scandalous than his own—to win respectability and even veneration from quarters that once damned him as little more than a smut peddler, albeit one with a killer sense of style and a terrific head for business. Maybe the seventy-seven-year-old Polanski just needs to stick around a little longer.

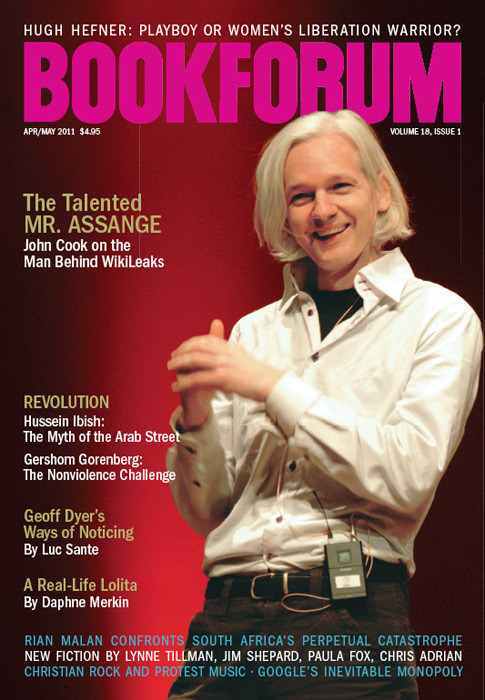

Over the past year or two, the media mainstream has lauded the eighty-four-year-old Playboy founder as, among other things, a heroic freedom crusader and an icon of the American dream. In Oscar-winning filmmaker Brigitte Berman’s near-hagiographic 2009 documentary, Hugh Hefner: Playboy, Activist, and Rebel, he’s a champion of civil rights and other humanitarian causes; Charles McGrath’s recent profile in the New York Times Magazine portrays him as an admirable, if slightly dated, survivor of the culture wars and a tirelessly plucky entrepreneur; and the tabloid treatment of Hef’s engagement in December to twenty-four-year-old Crystal Harris—erstwhile Playmate and reigning queen of the inexplicably long-running reality show The Girls Next Door—has bordered on wondering admiration at the old guy’s moxie and, um, endurance.

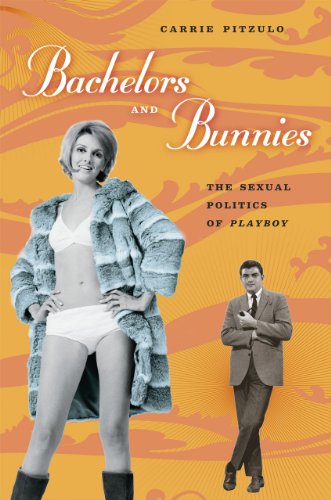

Hef’s role on Girls, where he plays a version of himself as the patriarch of a family of nubile Bunnies (all of whom he’s purportedly sleeping with), has introduced him to a brand-new audience of—surprise!—young women between the ages of eighteen and thirty-four. They, too, can’t seem to get enough of “Puffin,” as one Girls Next Door veteran dubbed him. So it was perhaps inevitable that in the midst of this major reconstruction job, an academic would weigh in to claim Hefner as a postfeminist icon. Cultural historian Carrie Pitzulo’s new book, Bachelors and Bunnies, touts the man and his magazine as staunch allies of women’s rights, early and essential players in the battle for female sexual liberation. It’s a catchy hook on which to hang a thesis, but it makes one wonder: Where’s the famous ex-Bunny Gloria Steinem when you need her?

Not that Pitzulo doesn’t have good reason to examine an important landmark of the sexual revolution for “complexity and contradiction,” as the common cultural-studies catchphrase has it. And contradiction is rife, mostly in the divide between the message sent by Playboy‘s raison d’être—the centerfolds et al.—and its editorial pages. Combing through reams of Forum and Advisor columns from the magazine’s heyday in the 1960s and ’70s (the primary outlets for Playboy‘s official stance on everything from politics to pantyhose), she finds substantial evidence of a surprisingly enlightened attitude toward women’s sexuality. The magazine, for instance, published editorials during the initial phase of the sexual revolution that denounced the double standard enshrining fidelity as the sexual norm exclusively for women; it promoted sexual freedom for not only women but also homosexuals, during a time when both positions were most definitely outré. And Pitzulo points out that Hefner, through his philanthropic Playboy Foundation, was an early supporter of a number of causes that aligned him with the feminists who decried his sexual politics—particularly the promotion of birth control and abortion rights.

Indeed, those causes were essential to Hefner’s vision of a world where women could freely engage in premarital sex without cultural censure. You could see this stance as enlightened or as a means of ensuring that the hedonistic lifestyle that Playboy sold to its male readers—the sophisticated bachelor pad stuffed with all the accoutrements of postwar bounty, the bottomless pitcher of martinis, the stack of jazz LPs on the hi-fi—was accompanied by plenty of available sexual partners, which, after all, was the point. Women, Pitzulo argues, were invited to be equal partners in this vision of sexual freedom. During a time when rigid social mores dictated that nice girls didn’t, the Playmates were presented as nice girls who not only did but enjoyed it, too, thus trumpeting to millions of male (and female) readers that single women had the right to seek their own sexual pleasure. In interviews Pitzulo conducted with a handful of Playmates from the magazine’s early days, some of the women say that posing nude was a form of rebellion against the puritanical cult of domesticity that prevailed during the cold war, while others claim it was a path to financial freedom.

Unfortunately, the argument Pitzulo advances here omits wide swaths of Playboy‘s—and Hefner’s—history. For example, she dispatches Steinem’s landmark article for Show magazine, “I Was a Playboy Bunny,” in two sentences, ostensibly because it’s beyond the purview of the book. But that’s a mistake, especially if she’s looking to draw a truly “complex and contradictory” portrait of her subject. Steinem’s piece is a grimly amusing chronicle of the mostly working-class Bunnies who waitressed at New York’s Playboy Club in the early ’60s. Lured into the job with blatantly false promises of high salaries and career advancement, they found that the job came with low wages, grinding hours, and the constant threat of sexual harassment (“My tail droops . . . those damn customers always yank it”). They were also, Steinem claimed, encouraged to make themselves amorously available to VIP (Very Important Playboy) customers. All of this seriously undercuts Pitzulo’s claims that women embraced the organization as a path to financial freedom and empowerment.

Similarly, the many dark tales of life inside Hefner’s notorious Playboy Mansion, most of them told by ex-Playmates, get nary a mention here. Stories persist to this day of drug-fueled orgies, during which Hefner and his male guests allegedly coerced women into sex acts that would make the girl next door blanch, but they are suspiciously absent from Pitzulo’s account. In any other chronicle of a media figure’s public life, such personal peccadilloes might not be relevant—but in Hefner’s case, the subject’s intimate life is synonymous with the product and so should factor into any discussion of Playboy‘s legacy to women.

But Pitzulo doesn’t probe this material, perhaps because much of her research depended on Hefner’s goodwill. The archives at Playboy West and Chicago were opened to her, and interviews with various editors and staff members, as well as with Hefner himself, pepper her accounts of the early years of the magazine. Needless to say, the view of Hefner in these Playboy-branded interviews is benign. When an interviewee does venture a critique, we never find out what the author thinks of it. Jennifer Jackson, in 1965 the first African-American woman to appear in a Playboy spread, candidly tells Pitzulo that Hefner was a “glorified pimp, clearly. I like him, but he was a pimp.” Curiously, Pitzulo lets that statement go without much comment.

And what better story than Jackson’s to illustrate the crux of the Playboy contradiction? Hefner was brave enough to feature an African-American Playmate long before other magazines would dare, but ultimately he was selling a woman’s body for profit. If he had donated money to the NAACP but was known to address his African-American manservant as “boy,” we’d probably be looking at his civil rights record very differently. Why should his personal regard for women as a series of interchangeable sex toys be exempt from the same judgment? Although it may be impossible to square the pimp with the liberal crusader for women’s rights, a historian has the responsibility to consider both parts of the conundrum. The irreconcilable puzzle Hefner presents is not unlike the experience of reading Playboy itself, which, in its golden age, was a phantasmagoric mix of high art, provocative politics, and . . . nude women. We never get a vivid sense in Bachelors and Bunnies of what this schizophrenic clash of content evoked, but for female readers who really did buy the magazine for the articles, the ride was a little unsettling, in ways obvious and not so obvious.

When my teenage girlfriends and I sneaked peeks at my brother’s stash, we’d study those little bios of the Playmates—”Miss January knits in her spare time and enjoys a stimulating game of chess with her granddad”—and howl with laughter. Hefner has often proffered those personal tidbits as proof against accusations that Playboy objectifies women. We just thought they were fake. We were more curious about the stuff between the photo spreads, which provided us with our introduction to the heady world of contemporary literature and dazzling cultural debate. But those glassy-eyed girls in the photos were embarrassing reminders that we really didn’t belong in that world. The girls looked dumb and boring, and we knew what they were there for. The message was clear: Sexy women aren’t smart.

Arguments that Playboy has somehow been liberating for women must finally address the question of what kind of power, exactly, has accrued to the women who represent the public face of the organization. Female viewers of The Girls Next Door can watch a reclusive and not particularly attractive octogenarian wander around his sepulchral mansion as an indistinguishable parade of bosomy blondes serve and service him for the chance to win pride of place as his “first girlfriend.” The exchange also buys them as much plastic surgery as any twenty-one-year-old girl could want, limitless access to an in-house staff of makeup artists and hairdressers, a bid for celebrity, and a lavish place to stay. The girls’ bedrooms are decorated in pink and white and resemble nothing so much as nurseries for little girls with a princess complex. The master of this domain is sometimes hard to please, and he’s capable of kicking any or all the girls out on a whim, immediately replacing them with a fresh supply of blondes (blondes are Hef’s “type”). The girls are not allowed to date other men while living in the mansion. Their curfew is 9 PM.

Such is the vision of female empowerment bestowed by Hefner and embraced by The Girls Next Door‘s young audience. And although it may be inevitable that pundits and historians, awaiting his eventual passing, speak of him in reverential tones, it might be wise to remain clear-eyed about his vision of the power arrangement between the sexes—and to remember that it’s likely to be around for a long, long time.

Linda DeLibero teaches film at Johns Hopkins University and is writing a book about Marlon Brando for Yale University Press.