I.

The central problem of writing about South Africa is that it is almost impossible to explain the country’s slow-motion catastrophe in terms that make sense to foreigners. Consider these headlines, culled from just a fortnight’s newspapers. Johannesburg’s City Press reports that the head of the ruling party’s Political School—set up to nurture “revolutionary morality” among thieving civil servants—is declining to explain how he has come to own two new BMWs and a Maserati. South Africa’s Sunday Times alleges rampant corruption in the administration of Northern Cape province. The same paper reports new attempts to silence a trade-union leader who likens the nation’s rulers to “hyenas” who feed off the poor. Elsewhere, we have FAILED BILLION-DOLLAR EDUCATION PROGRAM; WHISTLE-BLOWER MURDERED; WIFE OF NIA CHIEF ON TRIAL FOR SMUGGLING COCAINE, the NIA being our CIA. And finally, the story of the hour: The National Prosecuting Authority has abandoned its investigation into the whereabouts of $130 million in bribes generated by South Africa’s notorious 1990s arms deal.

In the West, scandals of this magnitude would topple governments. Here, they are almost meaningless. Most will never be pursued or resolved satisfactorily. The electorate will not stand up and scream, “Enough!” In many cases, the alleged culprits won’t even be investigated, and the incompetent bureaucrats who presided over the education fiasco will not be fired. In a week or two, these stories will be blown off the front pages by equally hair-raising scandals, most of which will also just fade away. It’s been like this for years, and there comes a time when you stop paying attention lest the drumbeat of bad news drive you mad.

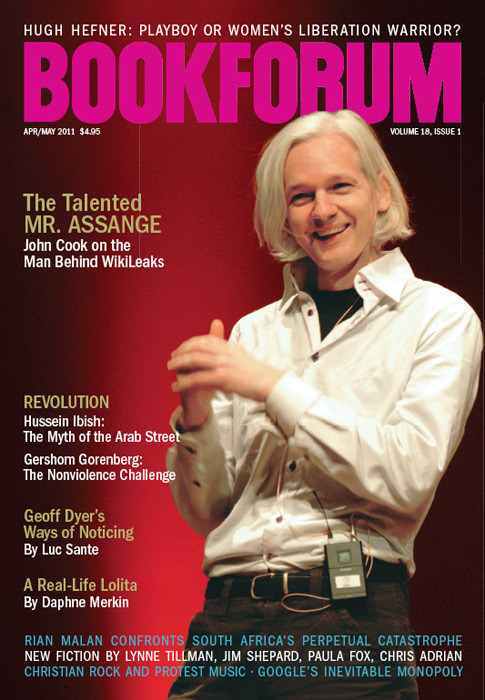

Against this backdrop, I didn’t exactly welcome the arrival of R. W. Johnson’s latest tome, because I knew it would further aggravate my dyspepsia. Johnson is an Oxford politics don who spent his teens in South Africa, hanging around the fringes of the Communist Party and fleeing into exile circa 1964, when the security police started asking uncomfortable questions. Back then, he was a slender young idealist. The Johnson who returned to live here in 1995 was a portly, Churchillian figure, armored with the sort of absolute self-assurance one associates with the British establishment. Decades of exile had turned him into a liberal in the stern nineteenth-century British tradition, meaning that he stood for free markets, free speech, and constitutional democracy and against the silly buggery of his former comrades in the socialist movement. Johnson was also a gifted writer, or perhaps I should say orator; essays and articles just rolled off his tongue and into a tape recorder, ready for transcription by his assistant. The resulting prose was imperious in tone and consistently offensive to the leftish journalists and academics who sought to control perceptions of Nelson Mandela and his Rainbow Nation. Johnson dismissed their output as “ideological wilfulness or sheer pretence.” They retaliated by branding him a racist.

In South Africa, in the mid-1990s, the term racist was indiscriminately applied to almost all critics of Mandela’s fledgling government. By this definition, Johnson was a very bad racist indeed. He described one of Mandela’s cabinet appointees as “utterly incompetent,” another as “disastrous,” queried the moral caliber of influential African National Congress donors, and warned that corruption was threatening to turn into a “Gadarene stampede” as the Spartan revolutionaries of yore eased into the business of governing Africa’s richest country. As a result, his work was effectively banned here—not by the government, but by editors who felt Johnson was undermining a noble experiment in racial reconciliation.

Such considerations didn’t apply in London, where the editors of the Sunday Times and the London Review of Books prized Johnson’s dispatches and published everything he sent them. Irked by the ex-don’s growing influence, left-liberals took to poring over his scribblings in search of errors and thought crimes. In 1998 or thereabouts, Mandela himself sent an emissary to Fleet Street to lay the results before British editors and demand that Johnson be silenced. The central charge was, of course, racism. Over the years, the ex-don’s teeming enemies have indeed found two plausible outbreaks of the dread disease in Johnson’s vast output. One was a passing reference to the manner in which “our enterprising Asian countrymen” had captured the ears of important ANC leaders. The other was a blog entry that drew a clumsy comparison between the desperate baboons who raid Cape Town’s garbage bins and the desperate economic refugees flooding into South Africa from failed states north of our borders. The resulting disputes are worth Googling, but they tend to obscure the central truth about Johnson: His early skepticism about the ruling party has been thunderously vindicated by the course of events.

[[img]]

Five years ago, such a statement would have got me lynched in polite South African society, but things have lately come to a pass where the disillusion is so deep that we might just be ready to acknowledge the painful truths embodied in South Africa’s Brave New World, Johnson’s magisterial history of the country in the first fourteen years of its liberation (1994–2008). This is a big book in every sense, 720 pages long and reminiscent in its tone and scope of the work of his (unrelated) namesake Paul Johnson, author of A History of the Jews and The Birth of the Modern. Both Johnsons are firmly opinionated and intolerant of messy ambiguity. Both have the ability to render the dreariest subject readable by clever deployment of anecdote and broad generalization. And both are inclined to annihilate those they regard as fools.

I’d hesitate to include Mandela in this category, because Johnson, despite his criticisms, admires the old man’s courage and praises his attempts to unite a nation divided by yodeling chasms of race and class. He also has a soft spot for the current state president, Jacob Zuma, the colorful Zulu polygamist who was elected in 2009. (Zuma and Johnson are of an age and share a nostalgia for the lush subtropical lowlands of Natal, where both spent their boyhoods.) Johnson’s real target in these pages is Thabo Mbeki, the power behind Mandela’s throne from 1994 to 1999, and state president in his own right for the nine years thereafter. In Johnson’s estimation, Mbeki’s rule was ruinous in every sense.

II.

Johnson sees Mbeki as a prince of darkness, simultaneously beset by crippling insecurities and overweening arrogance. The former rendered him paranoid, prone to imagining enemies where none existed and pathologically sensitive to criticism. The latter caused him to view himself as Africa’s savior, an architect of grandiose foreign-policy projects that consumed most of his energy while his own country began to show worrying signs of a slide into classically African dysfunctionality. Johnson describes the symptoms thus:

A government increasingly racked by corruption and incompetence. Illogical policies blindly pursued with predictable and dire results. All power concentrated in the hands of an over-mighty President who attempts to prolong his rule. The decay of infrastructure through poor maintenance alongside a pronounced taste for prestige expenditures. Power cuts for the people, the arrogance of power for the elite and an ever-growing chasm of inequality between.

There are many books about South Africa, but Brave New World is the only one that comes close to explaining how we got to this point. For me, reading it was like awakening from a self-induced coma; every third page resurrected an episode I’d blocked out of my consciousness in hopes of preserving at least a vestige of optimism. Let’s start with the death of Chris Hani, cut down by a white right-wing assassin in 1993. Hani was the popular leader of the ANC’s insurrectionary faction and, as such, Mbeki’s chief rival in the race to succeed Mandela. South African Communists have always maintained that Hani’s murder was the result of a vast and somewhat improbable conspiracy orchestrated by someone close to Mbeki. Johnson resurrects this theory in the opening pages of Brave New World and likewise fails to sustain it, but no matter: The real purpose of his thriller-novel prologue is to establish Mbeki as a deep schemer, perpetually engaged in a three-dimensional chess game against anyone who would threaten his rise to power.

By 1996, he’d sidelined Cyril Ramaphosa and Tokyo Sexwale, key rivals in the struggle for leadership of the ruling party. In 1998, he picked off Matthews Phosa, a lawyer who served as premier of Mpumalanga, one of South Africa’s most beautiful and unspoiled provinces. Shortly after coming to power, Phosa discovered that members of his cabinet were on the brink of concluding a secret deal with a Dubai-based hotel group that was willing to pay three billion dollars for exclusive development rights in the province’s game parks. The politicians were planning to collect lavish commissions, but Phosa exposed their scheme and ordered a crackdown. Instead of backing him, Mbeki sided with the miscreants, reversing their suspensions and eventually promoting two to positions of greater power. Phosa, on the other hand, was driven into the political wilderness. His crime? He was intelligent, charismatic, and popular with the party’s rank and file. As such, he was a threat to Mbeki and had to go.

As Johnson says, episodes like this—and there were many—sent an unfortunate message to ANC politicians and civil servants: Mbeki was willing to overlook sins of venality in return for political support. What made this dangerous is that Mbeki, once he became president, commanded a giant patronage machine bent on placing all South African institutions under the control of loyal ANC cadres. In theory, this implied loyalty to the party or to “the revolution.” In practice, it meant loyalty to Mbeki. Those who obeyed this unspoken rule were protected. Those who didn’t found themselves in trouble.

In the former category, we find figures like Dr. Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, the tragically incompetent health minister who made South Africa a laughing stock with her bizarre proclamations about alternative cures for aids—“garlic, olive, beetroot, and the African potato”—in the 1999–2003 period. In the latter, we find Zuma, Mbeki’s deputy, who pocketed about two hundred thousand dollars in payments that allegedly originated from a French arms manufacturer. This was a mere thousandth of the total paid out in arms-related bribes, but Zuma dared to imagine that he might topple Mbeki and step into his shoes and was thus singled out for prosecution. Those who hogged the balance presented no threat and proved untouchable.

[[img:2]]

Interestingly, Johnson provides no evidence that Mbeki was personally corrupt. He was an otherworldly figure, bookish and intellectual, with his eyes on a prize far higher than filthy lucre. Indeed, he seemed to live in a fantasy in which he starred as the eminent statesman, forever stepping off the presidential jet and striding up the red carpet into a forest of microphones to deliver a speech whose intellectual power caused adoring throngs to weep, cheer, and kiss his feet. The theme of these speeches—and again, there were many—was Africa’s sufferings at the hands of colonialists and imperialists, and the appalling condescension with which the continent was presently viewed by whites everywhere. In Mbeki’s estimation, this perception—or rather, misperception—was the root of Africa’s problems. And the cure was the African Renaissance, his project to remake Africa’s image.

In theory, the Renaissance project was a sort of moral-regeneration campaign, aimed at putting an end to the postcolonial tradition of one-man rule by authoritarian kleptocrats. But Mbeki could never say this too directly for fear of confirming the very perceptions he was trying to eradicate. He was also deeply concerned about the dignity of African leaders, starting with himself, which meant that any criticism had to be phrased in terms so oblique and flowery as to be meaningless. Mbeki’s greatest sins, writes Johnson, were grandiosity and bombast: “He wanted to lead Africa, to revolutionize it . . . to speak for the South—and to be regarded as a major intellectual. These were absurdly ambitious goals, driven by arrogance, based on little that was real. . . . There was no leadership because there was no humility and no realism.”

This might strike you as an exceptionally harsh thing to say about a leader who was, after all, making the correct noises about democracy and human rights. But Johnson is right. Mbeki never had much to say about nearby Angola, where the entire economy is controlled by the ruling dos Santos family, or about neighboring Mozambique, where the head of state is simultaneously the nation’s richest man. He couldn’t even bring himself to criticize Robert Mugabe, the cocky little martinet who reduced neighboring Zimbabwe to a basket case.

III.

When Mugabe took power in 1980, Zimbabwe was regarded as one of Africa’s jewels, a country with good infrastructure, deep soil, and a thriving agricultural sector, whose exports were the country’s largest sources of foreign earnings. At the outset, Mugabe himself cut a Mandela-like figure, going to extraordinary lengths to allay white insecurities and paying close attention to reform of the educational system. In this regard, his efforts were wildly successful, producing a generation of luminously self-confident youngsters, almost all of whom seemed able to quote Shakespeare and hum Handel.

But with this came a tendency toward skepticism and freethinking that didn’t sit well with Mugabe. When the nation rejected (in 2000) constitutional reforms that would have extended his increasingly corrupt rule for another decade, Mugabe turned nasty, organizing mobs to drive white farmers off their land—a move intended to restore the dictator’s popularity with the masses. Instead, it destroyed the country’s banking system, which in turn led to soaring inflation and generalized economic collapse. With most of his subjects facing starvation, Mugabe and his generals resorted to naked repression.

This is the subject of The Fear, Peter Godwin’s latest work. Born into a liberal family in Zimbabwe’s Eastern Highlands, Godwin has written several excellent books on his country’s torments, including When a Crocodile Eats the Sun (2007), an account of his family’s descent into abject poverty after the great collapse. In 2008, Vanity Fair sent him to cover an astonishing story—Mugabe, for reasons best known to himself, had allowed Zimbabwe’s latest election to proceed more or less freely and, when it became clear that he had lost, indicated that he was willing to accept the outcome and step down.

Godwin arrived in Harare to find the capital in a state of euphoria, but the party came to an abrupt end when authorities suspended the vote counting. Early results had shown opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai winning by a comfortable margin, even in Mugabe’s strongholds. But Zimbabwe’s rapacious “vulture” caste—an agglomeration of army generals and their business cronies—refused to surrender its privileges and prevailed on the aging dictator to dig in. When the counting resumed, Mugabe’s support showed a sudden and inexplicable surge, boosting his share of the vote to 40 percent and pulling Tsvangirai under the 50 percent required for outright victory—an outcome that necessitated a runoff.

What followed was macabre. The ethnic cleansing of Zimbabwe’s white farmers had been cruel and violent, but it had claimed relatively few lives; people were beaten and humiliated but seldom murdered. Similar tactics were now applied to Zimbabwe’s “disrespectful” voters. It was as if Mugabe, a God-fearing Catholic in his boyhood, had instructed his thugs to stop short of committing murders for which he might have to answer at the Pearly Gates. That’s one reading, at any rate. Godwin presents a chilling alternative: Mugabe calculated that his aims were better served by leaving his maimed and terrified victims alive to testify about the horrors awaiting anyone who dared vote against him again.

Godwin often visits Johannesburg on his way to Zimbabwe, and I have seen him reduced to apoplectic rage by the standing ovations accorded to Mugabe in the outside world, where some still regard him as a hero. At its heart, The Fear is a beautiful and terrible weapon against such stupidity, a book that thrashes the reader almost as relentlessly as Mugabe thrashed Zimbabwe’s electorate in the run-up to the second round of presidential elections. Each scene is more horrifying than the last, though they’re all similar: Mugabe loyalists, backed by elements of the military and the dreaded Central Intelligence Organization, surround a village that voted for the opposition, single out a few leaders, and subject them to unspeakable tortures: breaking jaws and limbs, raping women, flogging buttocks until the flesh disintegrates and falls away, exposing the bone beneath. Godwin seems mesmerized by the horror, incapable of tearing his eyes away. Ultimately, this becomes a drawback, as he concedes. “I often know now, before they speak, what they will say next,” he says, after days of interviewing the victims of what he calls “this torture factory.” But he carries on anyway, driven by the compulsion to record the sustained and indeed “industrial” cruelty of it all.

Which is not to say there are not moments of respite. The rains come, antelope cross a lonely road, survivors crack brave jokes about their hopeless situations. In one particularly sweet passage, a battered opposition activist named Roy Bennett describes an “incredible honor” done to him during a recent spell in one of Mugabe’s dungeons. Wide-eyed guards bring him a tiny vial of sacred medicine, telling him it was sent by ambuya Mapoka, the awesomely powerful spiritual leader of the Ndau people. The ancient crone has come down from the mountains to secure a white man’s release, and when it happens, she is waiting for Bennett at the prison gates; she calls him “my child” and begins to weep.

Such anecdotes suggest that Mugabe’s tyranny is forging unbreakable bounds of love between black and white Zimbabweans, an outcome he might not exactly welcome. But this is not Godwin’s theme. He soon returns to the Great Thrashing, following it until rival presidential candidate Tsvangirai throws in the towel, hoping his withdrawal from the race will put an end to the cruelty. It doesn’t. The thrashings continue, now with a view to warning the masses not to shame Mugabe by abstaining. They have to vote and to vote for the president. So they do, and Mugabe is returned to power with his dignity intact.

As for Mbeki, the godfather of the African Renaissance backed Mugabe from the outset, shielding him against condemnatory United Nations and Commonwealth resolutions and blocking the Human Rights Commission’s attempts to investigate his atrocities. South Africans were told that Mbeki was working behind the scenes to prevent Zimbabwe’s implosion, but the country imploded anyway, driving millions of refugees into South Africa, where they sat on street corners, attempting to exchange worthless billion-dollar Zimbabwe banknotes for bread crusts. Zimbabwe’s implosion had become part of our implosion, and still Mbeki remained silent. Actually, that’s not true. As the Great Thrashing began, he made a state visit to Zimbabwe, where he and Mugabe were photographed smiling and holding hands, a traditional expression of affection between African males. Mbeki said there was “no crisis” in Zimbabwe.

IV.

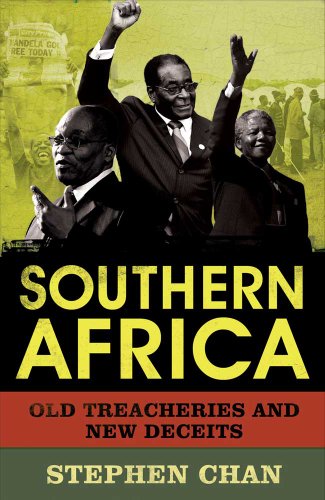

This telling moment is not mentioned in Southern Africa: Old Treacheries and New Deceits, Stephen Chan’s analysis of the present state of the region. A modish chap with shoulder-length hair who teaches at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies, Chan ran the Commonwealth’s southern African operation in the early ’80s, and one gathers he supported Mbeki and Mugabe in their revolutionary heydays. Five years ago, a man of such progressive inclinations might have attempted to eviscerate Godwin and Johnson, but now, he barely bothers; all that’s left is to place the heroes of yore in a broader historical context. Old Treacheries is fairly successful in this regard, reminding us of Mbeki and Mugabe’s roles in the liberation struggle and offering some pop-psych insight into their motivations. This renders both men more human and slightly more likable, but only at the cost of downplaying their less pleasant sides. Chan devotes just one paragraph to the gory details of Mugabe’s Great Thrashing, and his attempts to portray Mbeki as a just and wise mediator are rather lame.

Six months after the hand-holding episode, Mbeki persuaded Zimbabwe’s desperate opposition leaders to enter a power-sharing peace deal with the man who had recently robbed them of their election victory and then beaten thousands of their followers half to death. Chan offers this as proof of Mbeki’s masterly diplomatic skills and a “breakthrough” for the African Renaissance, but the outcome suggests otherwise. Mugabe held on to the critical police and military portfolios, threw Bennett back into prison, and routinely ignored his coalition partners’ helpless appeals for fairness and justice. In recent months, he has taken to thrashing his opponents again, and forty-six Zimbabwe democrats have just been charged with treason. Their crime? Watching video footage of the Tunisian uprising.

Alas, poor Stephen Chan. It must be a bitter thing to discover that the idols of one’s youth are in clay up to their armpits. Indeed, the situation is now so dire that Chan is forced to turn to former apartheid leader F. W. de Klerk for an upbeat closing assessment. Being an Afrikaner, ex-president de Klerk is less easily dismayed by Africa than your average liberal. In fact, he’s recently taken to playing the role once filled by Mandela, urging the troops to keep their spirits up and remember that we are not entirely done for. In the communiqué quoted by Chan, de Klerk limns the performance of our national rugby squad, commends our successful staging of last year’s soccer World Cup, and draws attention to minor economic miracles, including slow but consistent economic growth and a tax harvest large enough to provide welfare grants to the poorest poor, thirteen million of whom now survive on state handouts. According to Chan, such silver linings make Johnson a Chicken Little.

V.

I’ll avoid contesting the issue, if you don’t mind, and close with a photograph that speaks more eloquently than any of us. It was taken just the other day in Cape Town and shows a blond girl, seminaked, draped over the hood of a sports car in a cavernous nightclub. Over her looms a jovial black man wearing Roberto Cavalli shades and a white tuxedo jacket with pink trimming. This is Kenny Kunene, who has recently become famous for all the wrong reasons. He is eating sushi off the model’s pale flesh while a gallery of leering drunkards applauds in the background.

Four years ago, Kenny was a penniless ex-convict. Today, he owns two Porsches, a BMW, and a Lamborghini. The source of his money remains a mystery, but there is a lot of it, and Kenny spends it lavishly, inter alia on parties where he sips Dom Perignon while eating sushi off the bodies of seminaked girls in a firestorm of camera flashes. These orgies are publicity stunts for Kenny’s chain of ZAR nightclubs, expensive joints that cater to rich black businessmen and their political friends. Some find the ZAR clubs obscene, given that most South Africans struggle to find enough to eat. Others, like Kenny’s “best friend,” Julius Malema, think Kenny is “a role model for the new generation.”

Julius is the thirty-year-old leader of the ANC’s Youth League, famous for his radical anticapitalist utterances and his admiration of Mugabe. Julius claims to speak for the poor, but his own style is the epitome of capitalist piggery—Breitling watches, Italian suits and shoes, giant SUVs and gleaming suburban mansions, also acquired by mysterious means. Julius is of course here tonight, sweat pouring off his shaven pate as he swills Kenny’s champagne. Julius can be quite dangerous when he’s in party mode. Last year, he punched one of his neighbors for daring to suggest that he turn the music down. Tonight, he’s picking a fight with Helen Zille, white leader of the Democratic Alliance, South Africa’s premier opposition party, which controls Cape Town and the surrounding region. Zille’s provincial administration is clean, efficient, transparent—and loathed by Julius, who bitterly resents that there remains a corner of the country where a “racist little girl” can tell him what to do. “Helen Zille will not close ZAR at 2 AM, like she does other nightclubs in Cape Town,” he declares. “The ANC owns ZAR—and we will party until the morning!”

Ah, what a rich canvas. It’s all here—the ostentatious display of wealth by a greedy elite, buffoonish utterances from a politician renowned for crass racial demagoguery, and the insinuation that this bacchanalia is taking place under the auspices of the ruling party and is therefore above the law. All that’s missing is the reaction, which was equally interesting. Older, wiser ANC leaders issued a furious press release, denouncing the eating of sushi off bikini-clad women as “antirevolutionary.” The mighty ANC Women’s League was equally scandalized. The press emitted a great roar of derision. Kenny was so viciously lampooned that he promised to behave, and even the bombastic Julius was forced to issue a grudging statement. It was a nothing event in the overall scheme of things, but it shows something worth remembering: The battle to save South Africa is far from over.

Rian Malan is a writer and musician who lives in Johannesburg.