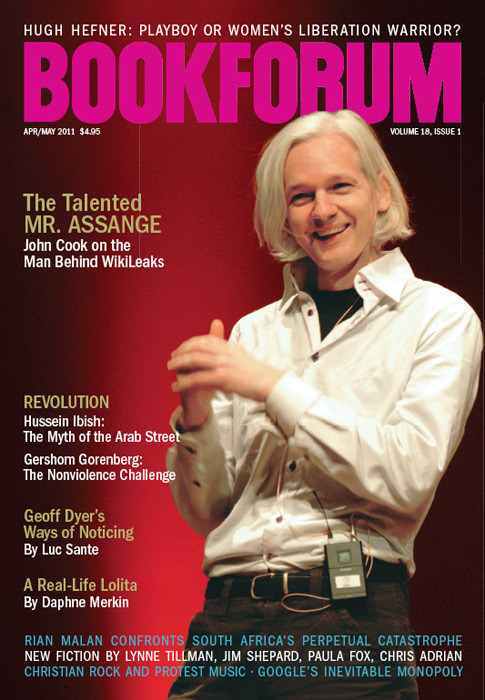

Chris Adrian’s prose is so alive with sweet and quirky phrasing, so comfortable with the sexual and the theological, and so optimistic in the face of putative certainties that readers may find cause for gratitude even in a novel that is foolish in conception and inept in structure. Such grateful moments are certainly rarer in The Great Night, Adrian’s latest, than in Gob’s Grief (2001) and The Children’s Hospital (2006), and they become rarer as the novel progresses. The Great Night is hampered by technical decisions rather than Adrian’s sentence-by-sentence conduct; there are flaws of narrative construction as well as of viewpoint, and the threat of whimsy has been nurtured rather than resisted. This has a trivializing effect on the characters’ skillfully elaborated predicaments—and an eroding effect on the reader’s goodwill.

The book’s title refers to a night in June, the shortest of the year, on which Henry, Will, and Molly are making their way, separately though with a similar lack of confidence, through San Francisco’s Buena Vista Park toward Jordan Sasscock’s house party. Henry, a pediatrician, has recently broken up with his boyfriend; Will, a tree surgeon, has recently broken up with his girlfriend; and Molly, a shopgirl, is mourning her boyfriend, who recently killed himself. The novel provides an immediate sense of what is at stake for the characters— Molly, for instance, feels “her couch pulling at her from way back at Sixteenth and Judah,” but forces herself on because her absence from the party would allow her to be typecast as a grief-stricken recluse. Jordan’s party becomes for all three characters the catalyst for dreams of renewal or escape—this will be the night that will change everything for the better. But elsewhere in the park and on its hill (“just beyond the thresholds of ordinary human senses”), there are forces beyond their control.

The copyright page of The Great Night identifies the book as a “retelling” of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, though it might be called a sequel, since the book features Oberon and Titania as characters, presumably after their adventures with Lysander, Hermia, and the rest. The spirit of Adrian’s book, at least initially, is more concerned with aftermath than expectation. His lovers are lovelorn, at the end of hope rather than on the cusp of its fulfilment, and Titania is mourning her son, Boy, whom Henry and other doctors have failed to save from leukemia.

There is an intriguing but by no means central question, for parodists, pasticheurs, and the like, about how to treat the cultural makeup of a fictional world whose events are dictated by an existing cultural product. John Banville’s wonderful novel The Infinities (2010) is set in a place called Arden, though its model was not As You Like It but the Amphitryon myth, which is both retold (Zeus seduces a woman disguised as her husband) and acknowledged within the world of the book (the seduced woman is to play a woman seduced by Zeus in a new Amphitryon play). By setting his tale in an alternate universe where, for instance, Shakespeare isn’t a playwright but a biographer, Banville freed himself from having to accommodate the myth on which his tale was based; he did so for reasons of strategy rather than of duty. The question of how to approach such things is trickier in Adrian’s novel, with both playwright and play being so famous, and with the tale being set among savvy San Franciscans. Adrian decides to let the question linger; we are simply to make the minor leap of faith that the play does not exist for these characters, though nothing else is different in the world they inhabit.

The novel is built on “meanwhile, elsewhere” plot juggling, familiar from Shakespeare’s plays and Sarah Jessica Parker’s television career. It was the former that the critic William Empson had in mind—along with work by Thomas Middleton, Robert Greene, and others—when he wrote that “deciding which subplot to put with which main plot” was “a form of creative work . . . at which one may succeed or fail.” Adrian’s failure is not in deciding which plots go together—this much was bequeathed to him by Shakespeare—but in devising how they should relate. The primary plot, the tale of the lost wanderers (Henry, Will, and Molly), initially runs parallel to a second plot, which takes place in Shakespeare’s faery kingdom. There is also a second subplot, in which Shakespeare’s theatrical troupe of “rude mechanicals” becomes a group of vagrants staging the Charlton Heston science-fiction film Soylent Green as a piece of propaganda. The reader is extended the privilege of being introduced to all three sets of characters before they are cognizant of one another. But a strategy that proves effective on the stage—in this case, dramatic irony—may adapt poorly to the page; there is surely less amusement for a lone reader knowing what the characters don’t over the greater length of a novel than for a communal audience at a play. There is also great frustration in being forced to register the difference, subtle but crucial, between suspense and waiting, as in the moments when the would-be partygoers refuse to believe the faeries are real. Adrian comes close to treating point of view as nothing more than a series of epistemic games, with the reader being invited to join a rather unappealing conspiracy with the author.

Adrian handled such things better in his first novel, Gob’s Grief, narrating events through the impressions of three characters, each of whom has lost a brother in the Civil War but none of whom is Gob Woodhull, the book’s protagonist. Gob spends the book building a machine that will bring back the Civil War dead; it is the job of the characters whose perspectives are given center stage to acquaint us with this determined dreamer and to reveal different sides of him. The book’s three sections move chronologically (from the early 1860s until the 1870s), so we see the same period, and some of the same events, from different angles. The book is a dazzling exercise in showing the fascination of things we didn’t know we didn’t know, whereas the new novel is concerned with alerting us to facts and details we know the characters don’t know.

The strategies of stagecraft haven’t served Adrian well, but you can see why the playful paradoxes and collapsing binarisms of Shakespeare’s play would appeal to him. As well as writing fiction—he was recently named one of the New Yorker’s “20 Under 40”—Adrian is a fellow in pediatric oncology at the University of California, San Francisco, and a seminary student at Harvard Divinity School; he has shown a tendency throughout his writing to view medicine as a kind of guesswork, full of contradictory and counter-intuitive thinking, and mysticism as a rational response to what we encounter and experience, the only place where hope might flourish. Hope for immortality, most of all. As well as Gob’s machine, in which faith takes metallic form, his writing deals with Ouija boards, ghosts, devils, images of the afterlife; the epilogue to the new novel contains Titania’s promise to “purge” Bottom of his “mortal grossness.” Adrian the pediatrician spends his time looking death in the face, while Adrian the seminarian speculates over what happens afterward—and these two personalities slog it out for influence over Adrian the fiction writer.

In the new book, Adrian writes well about his characters—that is to say, he invents and develops them in good prose. We meet Henry in the second paragraph, and by the end of it, the acquaintance is an intimate one: “Henry generally sought out blame, being comfortable with it, having been blamed for all sorts of things [and] crimes he had only barely committed, at ease in the habit of culpability because he had an abiding suspicion, nurtured by his mother and fostered by an unusual amount of blank history in his childhood, that he had once done something unforgivably wrong.” Will is introduced to us as a heterosexual who lives in the Castro: “He felt a kinship with those lonely souls drifting through the muffling darkness, rubbing up against one another, accidentally burning one another with the tips of cigarettes.” And he pursued a promiscuous lifestyle while in a relationship with “the most wonderful woman on earth”: His “unwarranted unhappiness” was among the causes of their breakup.

Adrian doesn’t seem to find writing of this smooth sort hard to pull off; more or less every sentence has a swift clarity and rhythmic crispness. But to what end? The book’s narrative approach is fundamentally incompatible with, or inhospitable to, Adrian’s ability to slip into the lives of his characters. He doesn’t need dramatic encounters for the building of character—give him a date of birth and an employment history, and he’s off. We know the characters very well very quickly, from Adrian’s rummaging in their biographies—not only the recent breakups but adolescent rites of passage, family troubles, professional challenges—so there is little to be gained, in terms of intimacy and comprehension, from their eventual convergence.

It is no more enlightening to wait for Henry to see Will, halfway through the book, as more than just “the dude in the plaid shirt” than it is engrossing to watch Will accept that he hasn’t suffered “a psychotic break on the way to Jordan Sasscock’s party”—that the “boy with the fake tail” is nothing of the sort. Once this has finally sunk in, the book’s San Franciscan and Shakespearean casts are united under an all-explaining fairy-tale umbrella, which even accounts for the “blank history” in Henry’s childhood. The Great Night is a disappointment not only in relation to Adrian’s previous novels but in terms of its own strangled strengths and unrealized possibilities—for the book’s mythological plot reduces, to the status of whimsy fuel and narrative data, a group of characters easily strong enough to power a novel on their own.

Leo Robson is the lead fiction reviewer for the New Statesman.