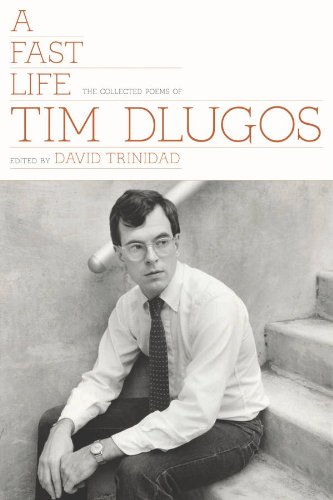

It might seem, on opening A Fast Life, that Tim Dlugos was born fully formed from the head of Frank O’Hara. Dlugos was undeniably an original, but his sophistication and finesse—acquired while he was still a student at La Salle College and immersing himself in the work of the New York School poets—showed from the very beginning, when he started writing at the age of twenty in 1970. His collected poems reveal no big stylistic breaks, no eureka moment when the poet turns the corner from juvenilia to maturity, but rather a continuous deepening of a consistent aesthetic. His life, on the other hand, was tumultuous: Dlugos thought he was heading toward a monastic existence before he discovered antiwar politics, poetry, and his own gay identity in short order. The rest is chronicled in the poems: an overwhelming hunger for experience fueled by drugs and alcohol as much as by sex and poetry, at least until he found AA in 1984, after which his writing went on hiatus for a few years and he once again found himself drawn toward religion. By the time he’d enrolled at Yale Divinity School and was accepted as a postulant for Holy Orders in the Episcopal Church in 1988—the same year he resumed writing poetry with his previous intensity—he had tested positive for HIV. He was first hospitalized for AIDS in 1989 and died the following year, at the age of forty.

In retrospect, Dlugos may be the great poet of the AIDS epidemic, above all in “G-9,” a remarkable long poem in short lines whose meditative prosody owes more to James Schuyler, perhaps, than to O’Hara. The poem, named for the ward at Roosevelt Hospital where Dlugos was being treated, is astonishingly clear-eyed in facing the fate he shared with so many of his friends—“There are forty-nine names / on my list of the dead, / thirty-two names of the sick.” Yet he finds a sort of peace in his gratitude for the gift that allowed him to face down his illness: “the unexpected love / and gentleness that rushes in / to fill the arid spaces / in my heart, the way the city / glow fills up the sky / above the river, making it / seem less than night.”

Dlugos was, of course, not only an AIDS poet, and his early work, which he began writing more than a decade before the onset of the AIDS crisis, is characterized by gossipy banter and a playful take on pop culture (see “Gilligan’s Island”). But it won’t do to exaggerate the changes that came over Dlugos’s work when he first got sober and then got sick. Under the wit of his earlier writing—but not very far under—was always that hunger for the transcendent that had led him to the Christian Brothers as a teenager, and for which his enthusiastic assent to the Baudelairian directive Enivrez-vous was perhaps just another disguise. Although Dlugos could turn out fizzy occasional verse at the drop of a hat, his best work never lost its connection to first and last things and to a kind of austerity of spirit underlying all the antinomian self-indulgence. A 1976 sonnet (he was a recurrent reanimator of that and other traditional forms) includes the unsettling realization that “Each great hope seems / to melt away like snow beneath the force / of spring, the waking life again.” What makes the passage so striking is the truth encapsulated in a reversal of the reader’s assumptions: One would have expected hope to be the warming sun that brings new life after winter, not the icy crust of illusion that melts away as it thaws. The sonnet’s presiding spirit is Rimbaud, whom Dlugos portrays more like an early Christian hermit absconding to the desert than a young poet turning tail on his vocation.

Dlugos kept on writing to ghosts, as in 1983’s “Spinner”; poetry could be communication between the living and the dead. One of his very first poems, about a walk in the country but rather grandly titled “Cosmogony,” written while Dlugos was still a student, concludes with the rumination “that corpses cannot speak, / not even lies.” I wonder whether he meant to argue against that common sense when writing his last poem, perhaps his best, twenty years later when he knew he was dying. In that poem, “D.O.A.,” Dlugos compares himself to the Edmond O’Brien character in the classic film noir, “perspiring / and chewing up the scenery” as he tries to discover who is responsible for his foretold death in the few days left to him before it occurs. This is another poem about a walk, this time not in the country but down Columbus Avenue, where Dlugos imagines that “the eyes of every / Puerto Rican teen, crackhead, / yuppie couple focus on my cane / and makeup. ‘You’re dead,’ / they seemed to say in chorus.” How did he get to this place? I can’t help quoting his answer to himself at the poem’s conclusion, at once his ars poetica and his apologia pro vita sua:

Lust, addiction, being / in the wrong place at the wrong/ time? That’s not the whole / story. Absolute fidelity / to the truth of what I felt, open / to the moment, and in every case / a kind of love: all of the above /brought me to this tottering / self-conscious state—pneumonia, / emaciation, grisly cancer, / no future, heart of gold, / passionate engagement with a great /B film, a glorious summer / afternoon in which to pick up / the ripest plum tomatoes of the year / and prosciutto for the feast I’ll cook / tonight for the man I love, / phone calls from my friends / and a walk to the park, ignoring / stares, to clear my head. A day / like any, like no other. Not so bad / for the dead.

In the absence of hope, there is still truth, pleasure, love. No, not so bad at all.

Barry Schwabsky is an American art critic and poet living in London. His books include Vitamin P: New Perspectives in Painting (Phaidon, 2002) and Opera: Poems 1981–2002 (Meritage Press, 2003).