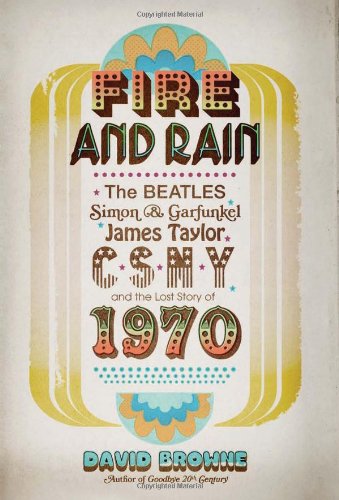

Reading David Browne’s exhilarating and meticulously researched Fire and Rain, I was reminded of an old Woody Allen stand-up routine about a costume party in which he was about to be hung by the Ku Klux Klan: “My life passed before my eyes. I saw myself . . . swimmin’ in the swimmin’ hole. Fryin’ up a mess o’ catfish. . . . Gettin’ a piece of gingham for Emmy Lou. . . . I realize, it’s not my life.” I lived through the same tumultuous year, 1970, that Browne documents in Fire and Rain and listened to much of the same music, and though our experiences were similar, our recollections are quite different.

But since Browne is a superb chronicler of popular music (author of, among other books, 2008’s Goodbye 20th Century: A Biography of Sonic Youth) and a fine social historian, I have to give in on most major points. For one thing, in my memory it was 1969—the year of the second Vietnam War Moratorium (which brought half a million people to Washington), of the Manson murders, of Woodstock and Altamont—that tore the fabric of American society. Browne is correct, though, in describing 1970 as strikingly turbulent. It was, he writes, “a year—a strangely overlooked one, in some regards—of upheaval and collapse, tension and release, endings and beginnings.” Student protests (such as the one that ended with the massacre at Kent State) and incidents of domestic terrorism (as many as twenty a week in California alone) were common fixtures of the news cycle.

It was also a time when the English-speaking world took its popular music very seriously. A somber British television reporter put it in perspective when Paul McCartney announced he was leaving the Beatles: “The event is so momentous that historians may mark it as a landmark in the decline of the British Empire.” Ambitious in its scope, Fire and Rain—the book takes its title from James Taylor’s biggest hit, which mourns a friend’s death from an overdose—tells the story of a pivotal year in the history of the counterculture through the triumphs and breakups of four sets of musicians: the Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, James Taylor, and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. These signature performers dominated the charts in 1970 and wound up competing at the 1971 Grammys (where Simon & Garfunkel won almost everything).

Among other things, Browne’s retrospective account stresses the striking degree to which all of these artists intermingled—socializing, attending one another’s concerts, and jamming together onstage. In retrospect, their music probably served to cool an overheated society down a bit that year; in October, shortly after Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin, perhaps the two most iconic musical figures of the Woodstock era, died from drug overdoses, President Nixon called together radio programmers, broadcasters, and officials from the Narcotics Bureau and the FCC to issue “dire warnings about the connections between drug abuse and the music . . . and radio executives were asked to screen songs for drug references. . . . No hard-and-fast rules were laid out, but the chilling effect was felt by everyone in the room.”

Browne effectively avoids sentimentality in recalling the music of his youth: “I don’t pine for my childhood . . . but I couldn’t resist revisiting a moment when sweetly sung music and ugly times coexisted, even fed off each other in a world gone off course.” I’ll give him that, but 1970 belonged to me as well, and I have to say that Browne and I don’t always park our car in the same garage. My musical memories of the time are crowded with the sounds of black artists whom Browne gives scant attention to or disregards altogether. I mean Sly & the Family Stone (whose Greatest Hits was released in 1970 and apocalyptic There’s a Riot Goin’ On the next year), Parliament-Funkadelic (whose first album came out in 1970), and, of course, the great Al Green (whose LP Green Is Blues was released in 1969; its singles crowded the AM airwaves the following year).

Browne also curiously neglects Joni Mitchell and Carole King, perhaps the first great female singer-songwriters of American pop music, who appear only as appendages to the male stars. (Mitchell was linked romantically to Taylor, David Crosby, and Graham Nash, while King was close friends with Taylor and Paul Simon.) Mitchell’s Ladies of the Canyon, issued in 1970, viewed the counterculture from a vantage that stretched at once backward (with the song “Woodstock,” later a huge hit for CSNY) and forward (the humorous “Big Yellow Taxi” was one of the first rock songs to deal with environmental issues). King’s groundbreaking albums, Writer (1970) and Tapestry (1971), seemed omnipresent in the pop and counterculture worlds alike. Frankly, the major work of both women has aged better, to my ear, than the later work of the Beatles or anything by Taylor and perhaps even Crosby, Nash, and Stephen Stills. (Not Neil Young, though; he alone in the band went on to greater music.)

That said, much of the music Browne writes about in Fire and Rain is less dated than the punk and new wave I was so enthralled with in the later half of the decade. In the end, the music of 1970 and ’71 represents the era’s most remarkable legacy, in spite of the drugs, feuds, and social tensions that stand out in the standard social histories; as Browne notes, all this great music materialized “not in a decade but in a mere eighteen months.”

Allen Barra writes for the Wall Street Journal, the Village Voice, and the Washington Post. His latest book is a biography of Yogi Berra.