What is it about the promise of a frozen treat on a hot day that can make a five-year-old wake up in the pitch black of 5:00 am and pad to his mother’s bedside to poke her unceremoniously and ask: “Is it time to make the popsicles?” (No. No, it is not. Not before daylight, and certainly never before coffee.) It is, I suspect, more than just a craving for sugar and cooler temperatures. I’m almost certain, in fact, that it’s the same thing that compelled me to wear a shirt with a repeating pattern of ice-cream parlors on it almost every single day the summer I was six, the feeling that makes me line up even now, when I should know better, for a soft vanilla twist with chocolate sprinkles the minute I see the season’s first ice-cream truck. It is the unquantifiable, slightly Proustian emotion that, as Charity Ferreira writes in her introduction to Perfect Pops: The 50 Best Classic & Cool Treats (Chronicle, $17), makes popsicles “equally adored by foodies, hipsters, and preschoolers.” They remind us, regardless of which—if any—of those categories we fall into, of years and pleasures gone by. They are a luxury masquerading as a simple dessert, ritual disguised as ordinary foodstuff (remember the Mad Men episode when Peggy lands the Popsicle account? “Take it. Break it. Share it. Love it”). It’s only a slight exaggeration to say that frozen desserts are one of the things that have bound humanity together over centuries and cultures. (If you feel like proving this, check out Fany Gerson’s Paletas: Authentic Recipes for Mexican Ice Pops, Shaved Ice & Aguas Frescas, which my popsicle sous chef recommends in particular for the Watermelon Ice Pops recipe.)

Not, of course, that my young helper—I had managed to hold him off until 8:00 AM— was thinking about any of this as we assembled our ingredients and began. With summer around the corner, we had been perusing several pertinent books together, including Perfect Pops. I thought it was time to move beyond pouring juice directly from the carton into popsicle molds and freezing it for dessert, and so, needless to say, did my son. That he was suddenly in possession of a mother who not only owned multiple books about how to make popsicles and ice cream but was also going to let him choose which ones to make was almost beyond belief. Being a child of action rather than skepticism, however, he took up the challenge without hesitation and settled on Chocolate-Vanilla Pudding Swirl Pops as his object of desire. He hacked away happily at a pile of bittersweet chocolate with a huge knife and then, when the two puddings were done, we spooned them carefully, in alternating brown and off-white layers, into our popsicle mold. Then into the freezer they went, to be unearthed for the kids to eat the following evening during a casual dinner with friends. When we released the first one from the mold in all its marbled chocolate and vanilla glory, I’m not sure whether he or I was more amazed at what we’d created. Drunk on our newfound powers, we wondered what other frozen delights might be within our grasp, and how soon we could start making them.

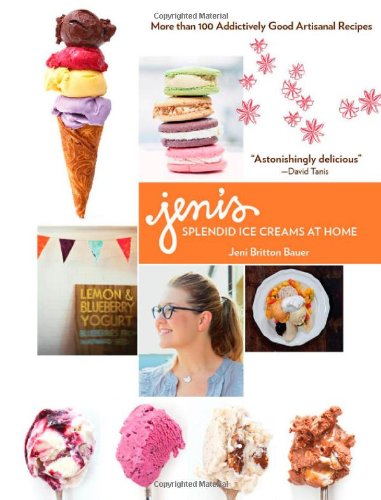

The answers to these questions were presented to me later that week, in the form of Jeni’s Splendid Ice Creams at Home (Artisan, $24) and a brand-new ice-cream maker I’d purchased for the occasion. Back in 1996, a young woman named Jeni Britton, who had “pink hair and lots of ideas and enthusiasm, but little business acumen,” opened an ice-cream stand called Scream in Columbus, Ohio. She whipped up her confections in an ice-cream machine no bigger than the one I had just bought (longing all the while for the fancy Italian stainless-steel commercial model), served most of her own customers in person, and generally had no idea what she was doing. Not surprisingly, Scream failed. But Jeni persevered through several courses of study in both ice cream making and business, one wedding, a job as a nanny, a few business partners, a bank loan, and a whole lot of Salty Caramel ice cream, until her store rose from the ashes as Jeni’s Splendid Ice Creams. Now, nine years, eight more stores, countless hand-labeled pints (available for purchase in thirty-one states), and a devoted following later, Jeni Britton Bauer has added this cookbook to her mini-empire, and it is divine. Which is why I found myself on a Saturday night pondering my options—Savannah Buttermint or Kona Stout? Bangkok Peanut or Brown Butter Almond Brittle?—whisk in hand, ready for action.

Without getting into too many technicalities, I’ll just say that there’s a lot of science (ratios of water, butterfat, starch, air, etc., etc.) involved in making ice cream, and that Jeni both explains it all very well and makes it possible to ignore her explanation entirely and just follow the recipes, if that’s what you prefer. Geek that I am, I read every word of her section on “The Craft of Ice Cream.” And then, emboldened by my totally superficial knowledge, I decided to start big with her signature Salty Caramel, which I happened to have tasted once when a Jeni’s-acolyte friend who travels to Columbus frequently on business made use of Jeni’s brilliant home-delivery option and brought it over. Even the fact that this recipe contains a special note about cooking sugar that opens with the words “Danger! This is the dry-burn technique” didn’t put me off. I felt I was in such good hands that I could do no wrong.

This turned out to be true. About an hour later, my dry burning of sugar and combining of cornstarch, cream cheese, milk, vanilla extract, corn syrup, heavy cream, and sea salt completed, chilled, and now spinning slowly in the machine’s freezer bowl, I began to think, “How the hell do I know when it’s done?” This was precisely when I happened across a page in the book, helpfully illustrated with an enormous photo of the exact same freezer bowl filled with freshly made ice cream ready to be transferred to the freezer, with an enlightening explanation beneath it that began, “How to Tell When Your Ice Cream Is Done.” I did what Jeni said, and the results were, if not quite as good as the original—my Salty Caramel was a little too dense, perhaps a tad overly sweet—pretty spectacular for a neophyte.

I was hooked. I spent days with visions of heavy cream and sugar sloshing in my head and nights dreaming in much the same vein. All I could think about was making ice cream, and so I did. There was a batch of Backyard Mint and one of the Darkest Chocolate Ice Cream in the World. Then, for a dinner party, a batch of Roasted Strawberry Buttermilk and one of Roasted Pistachio. (While I am all for other people making Jeni’s Olive Oil or Chamomile Chardonnay, I’m more of a traditionalist at heart.)

I dished it up at the meal’s end and, looking around the table at my guests’ faces as they ate and proclaimed their allegiance to one flavor over the other (the pistachio took it), watched the range of reactions. There was pleasure and a hint or two of being overstuffed—my husband had made leg of lamb—but too polite to refuse dessert. There was amazement, or perhaps amusement, at the sheer folly of someone having made something it was so easy to just go out and buy. All around, there was a kind of childish giddiness that lapsed, here and there, into a faraway look. Everyone in my dining room, it was clear, had had a long, happy relationship with frozen treats, some of us with mango ices in India, others with the Good Humor truck on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue or a Baskin-Robbins in Santa Monica; the lovely ghosts of all those sweets of yesteryear were with us in the candlelight.

And for you? What brings them back? The jingle of the Mister Softee truck fading away in the warm twilight? The memory of being up past bedtime, possibly in your pajamas, waiting in line at the local spot? The joy of taking your own children, as I do now, on a similar escapade? Or is it the chilly magic of a fruity ice in a slightly damp paper cup purchased from a little cart that transports you back thirty years in a split second even as it’s dying your tongue a noxious color? Whatever your answer, the specifics don’t really matter. It’s summer, as it was, is, and ever shall be.