Best sellers of yesteryear often don’t wear well, so I have only recently read Lillian Smith’s Strange Fruit, in spite of having a sense of its political importance and iconic place in the canon of southern literature (and despite having once received a prize named after the author). I was expecting a tract and so was astonished by its amazing success as a work of art. Smith is pitch-perfect in capturing a great range of voices among both races and all classes of the 1920s rural and small-town South, in a style that might be a fusion of Zora Neale Hurston and the early Eudora Welty. Her phrasing and timing, in each episode and in the structure of the whole, are rock solid. Her oblique rendering of the lynching at the novel’s climax is masterly, worthy indeed of the Greek tragedians (and probably influenced by them).

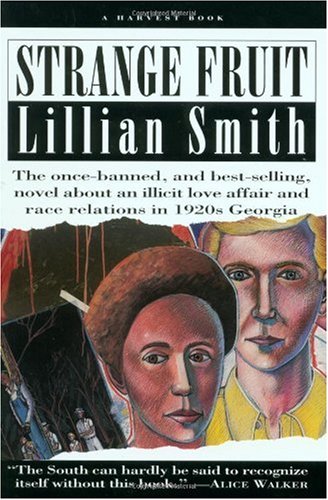

One would think that such a book would feel dated, since barriers to interracial love and marriage have been drastically lowered, even in the South, if not entirely removed. (When published, the novel was banned by the US Postal Service.) It doesn’t, mainly because it really is a love story, though a most unhappy one. Remarkably, Smith induces almost as much sympathy for the faithless lover, white Tracy Deen, as for the betrayed one, colored Nonnie Anderson. Watching Tracy dragged back into the culture that raised him and thus failing to live up to his best self is enough to make readers tear their hair out. The lynching—however awful—is peripheral compared with the depiction of psychological devastation.

We may still hope that someday race relations in this country will become completely healthy; till then, Strange Fruit has a lot to teach about what blacks and whites secretly think of each other. Unfortunately, human beings will never stop destroying what they love through disregard, and for that sad reason this novel will always retain its disturbing freshness. In that respect, as in many others, Strange Fruit stands in contrast to the antebellum romance Gone with the Wind, which hit best-sellerdom only a few years before by being the sort of thing that a mass of middlebrow readers could be expected to like. Smith’s much more sophisticated and telling novel probably needed (like Ulysses) the double-edged benefits of scandal and censorship to reach as many people as it—fortunately—did.

Madison Smartt Bell has published sixteen books of fiction. His most recent novel, The Color of Night, was just published by Vintage.