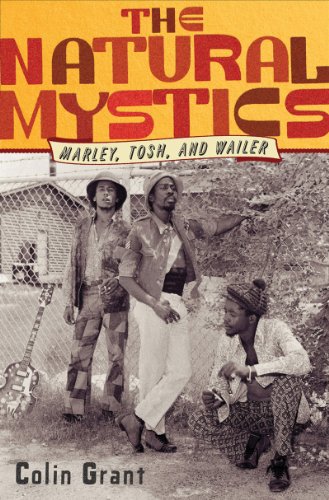

Colin Grant knows how to hook a reader with a compelling set piece. Grant, a BBC radio producer and independent historian, opens his study of the golden age of Jamaican reggae, The Natural Mystics, with a vignette from a 1990 concert at the National Stadium in Kingston. The concert was billed as “The Greatest One-Night Reggae Show on Earth,” but when Bunny Wailer, the last survivor of the most influential reggae band of all time, took to the stage, something disgraceful happened. He was booed off by the young crowd, a hail of bottles smashing around his head.

Twenty years earlier, he would’ve been greeted like a prophet—as would his acclaimed bandmates Bob Marley and Peter Tosh. These three performers, better known as the Wailers, revolutionized roots reggae and, to an extent, the Rastafarian faith, by broadcasting a black genre of oppositional music and religious belief to a multiracial audience of devoted followers around the world. What had changed so drastically since the band rose from the Trench Town ghetto, “empire of dirt”? They’d ushered Jamaican music—and more broadly, Jamaican experience—off the island and onto the world stage with such hits as “Stir It Up,” “Get Up, Stand Up,” and “I Shot the Sheriff.” The Wailers’ music, hymning equal rights and justice, seemed to have universal appeal. So how could reggae’s reign end with such brutal rejection? Grant leads with this question, and answers it simply: “A cultural coup had taken place.”

In formal terms, the progression of this overthrow is easily rehearsed: Dancehall overtook roots reggae, just as reggae sprang from ska, which had replaced its precursor, mento. But The Natural Mystics treats music as just one of the many coups, rebellions, ruptures, and seismic shifts that have shaped the revolutionary culture of Jamaica, where “history lies just beneath the surface.” If this book were simply a fan’s chronicle of the Wailers’ rise to fame, it wouldn’t be nearly as good as it is. One of its principal sources, Bunny Wailer (formerly Neville O’Riley Livingston), proves an elusive and evasive interview, but this winds up being a boon: Grant is forced to be a pilgrim rather than a strict biographer, blending research about the history of the island and information about the life of the band with accounts of the lives of other Jamaicans, known and unknown. The result is a penetrating and prismatic meditation about how patterns of cultural production are cast by place.

As any visitor who sidesteps the resorts can tell you, in Jamaica, past is present. Or as Grant shrewdly observes, “A sentence that begins in the present, ends in the Morant Bay murders of 1865, having called in on Frome in 1938 and memorialized the euphoria of 1962’s independence along the way.” He shows us how the violent Frome rebellion, which defined the era in which the original Wailers were born, was both influenced by the bloody slave revolts of the nineteenth century and an influence on the political turbulence and “undeclared civil war” of the 1970s that defined their adulthood. Such violent convulsions in the political life of the island pulse through the text like a hard-driving rocksteady beat.

Grant, for his part, is more than a detached visitor to Jamaica—he’s the British son of Jamaican immigrants, and the Frome rebellion is also a part of his family lore. In one of many turns from the historical to the personal, he shares the account of his grand-father, a police constable commanded to “shoot to kill” the disaffected laborers who’d set about protesting their pitifully low wages at the Tate & Lyle sugar factory by setting fire to the cane fields. As Grant writes, Tate & Lyle was a vestigial arm of the slave era, as well as a powerful symbol of the British Empire—and his grandfather, mindful of the injustices that kept the miserably deprived workers tied to the plantation, acted grateful for his comparatively plum job. (At the same time, in his reminiscence of the incident, the old man omits mentioning whether he obeyed the officer’s brutal command.)

Such lurches into personal narrative make for some of the most effective passages in The Natural Mystics—all the more when Grant uses his insider/outsider perspective to implicate himself. He’s flummoxed, for example, when a roadside fruit seller calls him a white man, then spits on him when he declines to buy a bunch of her rotten bananas. However, he refuses to indulge in the sort of guilt or self-pity that might assail a man of relative privilege; instead, he uses the encounter to ruminate on Jamaica’s lingering pigmentocracy, as well as the island’s gross divisions of class. A vexed conversation with a psychiatry professor at the University of the West Indies about the problem of Jamaican absentee fathers illuminates the author’s analysis of the Wailers’ lives (both Marley and Tosh were abandoned) and of the life of an island where “there seemed almost to be a pathological emphasis” on procreation.

Grant’s previous book is the impeccably researched and equally gripping Negro with a Hat: The Rise and Fall of Marcus Garvey (2008), which opens with a prologue touched by heartbreak. (Disgraced as a charlatan for having failed to forge a “United States of Africa” and forgotten in London, where he was weakened by a stroke, Garvey came across his own obituary two weeks before his death.) So it’s no wonder that we meet the father of black nationalism again here. This time, we learn about Garvey as a figure who presaged the Rastafarian movement that drew the Wailers into its heart, giving resonance and symbolism to so many of their lyrics (mostly penned by Marley). In two particularly meaty chapters, “And Princes Shall Come out of Africa” and “On Becoming Rasta,” Grant unpacks the basic tenets of the Rasta faith, including the central embrace of the divinity of Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie, who appealed to the Rastas as an archetype of black independence, sovereignty, and pride.

Part of Grant’s project is to pose the reggae stars themselves as archetypes of modern black manhood: Retreat and live (Wailer, the mystic who withdrew to farm), fight and die (Tosh, the rebel who was murdered in 1987), or accommodate and thrive (Marley, the megastar who succumbed to melanoma in 1981). As Grant plots out their biographical arcs, he skillfully conveys how tightly bonded the three were—not just as a creative team but as a band of brothers. In fact, Marley’s mother and Wailer’s father were lovers and had a child together. The two boys grew up under the same roof after moving from Nine Miles to the slums of Trench Town, where they linked up with Tosh. Adding to the ties that bind, Tosh later had a child with Wailer’s sister. In other words, these men were a family, in more than a metaphoric sense. By the time we get to the part where the trio dissolves in 1974, we feel the pain of their divorce because we’ve learned so much about their decade-long struggle to make it.

And finally, we meet the last remaining Wailer himself. Grant catches up with the recluse as the book nears its end. Bunny Wailer refuses to be direct about the disastrous night in 1990 when the rise of dancehall music found him on the receiving end of a shower of broken glass. Grant puts forth the question millions no doubt wish they could. Wailer’s answer almost seems like a gauntlet thrown down before him.

So what was it like to play with Peter and Bob? The mystic’s reply is, for once, direct and impassioned: “It was like the Children of Israel gathered around the Ark of the Covenant. It doesn’t happen every day, but when it does, it’s something to write about.”

Emily Raboteau’s Searching for Zion is forthcoming from Grove Press in 2012.