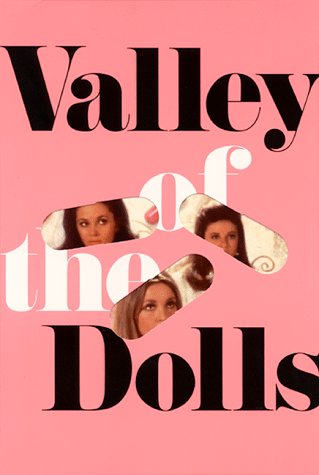

Jacqueline Susann’s roman à clef Valley of the Dolls was hated by high-culture critics when it was published in 1966, though it quickly became the year’s best seller. The novel follows three friends, Anne, Neely, and Jennifer, as they try to make it big in show business and find true love. Even when their dreams are partially realized, they cost the women an unbearable amount of frustration and heartbreak.

The New York Times called the novel part of the “narcotic” genre of literature, which has its reader “float[ing] down the river of lethargy,” but that’s nuts. Reading the book feels more like hurtling down Niagara Falls—driven by a torrent of sex, drugs, and doom. The panic with which one turns the pages is like the mixture of curiosity and fear that accompanies reading the Oedipus myth. The protagonists can’t do anything to escape their terrible fates, and each choice binds them closer to their destinies, yet there are no other choices. Just as in the myth, where things cannot turn out well for humans, in Valley of the Dolls nothing can turn out well for women past thirty.

Since their fates are inevitable, the book is filled with advice, the sole consolation of the desperate. Every character is an authority to every other, and they constantly offer useless and suffocating maxims: A man must feel he runs things, but as long as you control yourself, you control him. It’s no surprise that legendary Cosmo editor Helen Gurley Brown (who took her post in 1965) once said, “I wish I had written [Dolls].” There’s a great overlap between the worldviews of Susann and Brown: If a woman can learn the rules and follow them, she can avoid being washed up and thrown out. However, the bleak picture Susann paints is always glossed over in Cosmo, which doesn’t dare complete the image of a woman after a lifetime of trying to do everything right: In the heroine Anne’s case, there’s “nothing left—no hurt, and no love.”

I’m sure many feminists of the late ’60s and early ’70s read Valley of the Dolls. Second-wave feminism blossomed in the years following its publication, and while Susann and Betty Friedan are rarely mentioned together, Friedan formed NOW the year Dolls was published. Both women wanted the opposite fates of Anne and her friends. Susann’s characters were a stark warning to women against any kind of dependency: on men, beauty, fame, pills, sex, or children. In a subtle way, Susann left only one path to happiness unexplored: the political revolution that Friedan and her allies enacted. While none of the novel’s characters took this route toward self-realization, millions of Susann’s readers would.

Sheila Heti is the author of How Should a Person Be?, which will be published in the US next year by Henry Holt.