How many secrets can one person have, especially a person who has made a living out of spilling them, ruthlessly mining his own experience for autobiographical monologues that brought him no small amount of fame and fortune? Not many, it would seem. But if you’re Spalding Gray, the writer and performer of self-revealing one-man performances such as Swimming to Cambodia and Gray’s Anatomy, you can have private secrets within performed secrets, unspoken confessions behind the public ones.

That, at any rate, is what emerges from the pages of Gray’s journals, a document of wrenching and exhilarating honesty, shot through with self-hatred but also with unremitting humor and several shades of irony. Once you start reading, the book draws you in with its dire, lunatic brand of introspection, almost as though you were listening to an emergency phone call from a close friend who can’t, or won’t, hang up until he’s done detailing all the reasons why he’s a fraud and why his life sucks and why it’s high time he put an end to it. The anguish is real, whether it be about Gray’s conflicted sexual identity, his ambivalent feelings about celebrity (he once described himself as “a connoisseur of ambivalence”), his bouts of depression, or his various phobias, but so, for long stretches, is the sly twinkle in his eye. At one point Gray compares his journals to John Cheever’s, and they do indeed have some of the latter book’s urgent candor and distilled insights about sexual compulsions, as well as the dissonance between public and private personas, especially in regard to outward success and inner feelings of failure.

Even if you never caught Gray in a live performance before his suicide in 2004—he jumped off the Staten Island ferry after suffering from a lengthy depression in the wake of a car accident—his reputation as an Ur-neurotic, someone who successfully wore his demons on his sleeve, was formidable. As a master of crafted confessions (he referred to them as a form of “talking cure” and would later in his life become involved with therapy and the psychoanalytic way of looking at dreams), Gray knew more than most how much the truth mattered. He insisted over and over again that he didn’t know how to fictionalize his life, despite the honing and shaping that went into his staged accountings. “I don’t know how to make things up.” This was his cri de coeur, his credo, explicitly stated in Swimming to Cambodia, the most celebrated of his monologues, the one that brought late-night TV appearances and offers from Hollywood. (It was the first of his performances to be turned into a film, in 1987, followed by three more.)

Perhaps the assertion was no more than a promise to his audience, a letter of intent attesting to the kernel of painful, unwieldy reality behind the glistening set pieces, but what becomes clear reading these journals is how hazardous Gray’s approach to his own experience was. If he couldn’t work it up into material worthy of a performance, he was left with no one listening, be it a live or screen audience, no witnesses to the black hole that was always threatening to devour him. “I see now how and why people talk out loud to fantasies,” he wrote on August 15, 1991. “They can’t stand the pain anymore, the loneliness.”

But the urge to transform every experience into an entertaining yarn came with its own price as well, a sense of hollowness and falseness that made Gray feel too much “like a performance machine.” The gulf between the truth and the appearance of truth, the undeniable space between real life and the narrated life offered for the enjoyment of audiences, was something that gnawed at Gray. It was a “double bind hazard”—“the audience applauds my assholeness which is transcended by my ability to tell it”—that underlay much of his adult existence. “My fear,” he wrote, “is that I will get so good at artifice that I will no longer lead an authentic life.”

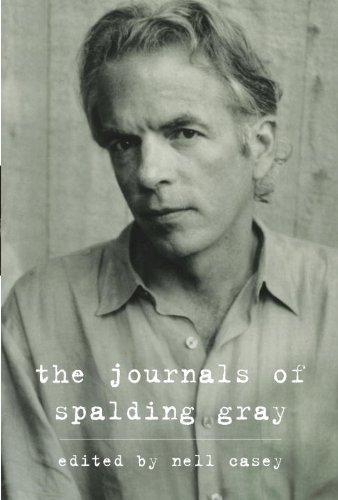

The journals allow us to see the unreconstructed Spalding Gray, the man who had many caddish instincts (especially when it came to women) and a core of “neurotic self-absorption”—qualities that don’t always benefit on the page from the self-knowing, humorous presentation he gave them onstage. The book has been superbly edited and annotated by Nell Casey, a novelist who has edited an anthology of writings about depression (Unholy Ghost); she also provides an excellent introduction. The journals open when Gray is twenty-five, preceded by a brief biography in which Casey fills in the details of Gray’s life up till then. Gray was born in Providence, Rhode Island, on June 5, 1941. He was the middle of three sons and had a particularly close relationship with his ebullient mother, a Christian Scientist who began having nervous breakdowns when Spalding was ten; she spent time in various psychiatric institutions, eventually receiving shock therapy, and killed herself in the summer of 1967 at the age of fifty-two. His father, a businessman, was a removed figure whom Gray blamed for introducing him to alcohol and instilling in him a sense of unmet longing. When he was fifteen, Gray, at the time an undiagnosed dyslexic, was sent to a boarding school in Maine “to bring his grades up and straighten him out,” as Casey puts it. In his senior year he discovered acting, playing a character in a mental hospital, and, after a brief stint at Boston University, went on to study theater at Emerson College. He landed a series of acting jobs after he graduated, and while he was performing in Jacobean playwright John Ford’s ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore in Saratoga Springs, New York, he began a romantic relationship with Elizabeth LeCompte, a student at nearby Skidmore College. While LeCompte finished her last year of college, a twenty-five-year-old Gray went to work at the Alley Theatre in Houston, where he had small roles in Arnold Perl’s World of Sholom Aleichem and Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s The Physicists, ruminated on his own inflated capacity for self-absorption (“It may be that I’ve gone so far into dwelling on myself that I’m not hip to anything that goes on around me”), and planned on meeting up with LeCompte (referred to as Liz) in Mexico.

The early journal entries show Gray responding to his mother’s death, news of which he received upon returning home from Mexico in August ’67: “In the ice box I found green jello made by a woman who was my mother and is now dead.” As a “hardcore Freudian existentialist” (which is how he described himself in Monster in a Box, another of his filmed monologues), he also examines his youthful instinct to “put on a show,” to prefer art to life, via a memory he has of himself as an eight- or nine-year-old wanting to frame the swing in his family’s backyard with a piece of set design. “For some reason,” he writes, “it was not complete in itself. I needed to comment on it. It has something to do with time and death—the swing being there then was not enough.”

By the spring of 1968 he and Liz were living in Manhattan, and Gray performed in various plays and took part in the Open Theatre Workshop as well as the Performing Garage, an iconoclastic theater group on Wooster Street led by Richard Schechner. “The big question is: do I want to be in a play more than I want to be in life? Or, do they (of course) become interchangeable a LIFE PLAY a playlife.” It was a question that Gray kept coming back to and that eventually propelled him in the direction of his pioneering confessional pieces, where the life/play distinction was artfully broken down. “To save me from the pain of my life I began thinking about how to put it in my next monologue. Public pain.”

During the ’70s Gray appeared to settle down, buying a loft with Liz in SoHo, a block from the Performing Garage, whose productions, such as Sam Shepard’s The Tooth of Crime, he continued to star in. He also began collaborating with Liz on the Rhode Island Trilogy, a series of well-received plays drawn from his own life; one of them, Rumstick Road, which opened in 1977, made use of his mother’s suicide and included excerpts from interviews Gray had conducted with his family and his mother’s psychiatrist. Gray played the narrator and stepped forward for the first time to directly address the audience. In 1979, he performed his first monologue, Sex and Death to the Age 14, sitting in front of a wooden desk with a little notebook; his solo show garnered praise from Mel Gussow at the New York Times, who described Gray as “one of the most candid American confessors since Frank Harris.”

On the surface, at least, all was going well, but the journals tell another story. Throughout this period Gray continued to wrestle with his anhedonia (“my inability to take pleasure in life”), his sexual compulsions—he acted in two pornographic films and experimented with homosexuality while on a trip to Amsterdam—and his mixed feelings about being in a long-term relationship. “I have to face what more seems to be the truth,” he writes, already fearing that his art was more crucial to him than any one person, however important, could be, “that I could only love Liz to the extent that she was incorporated into ME, my work, my fears.” He also continued to flirt with suicide (on a list of nine identities for himself that he composed in the summer of 1976, “a suicide victim” is causally noted along with “a world traveler,” “a Zen monk,” and “a movie star”) and the fantasy of becoming a child therapist. Meanwhile, he denigrated the audience that came to see his shows for using him as “their jester,” referring to himself as “a kind of unhappy Christ figure—a Woody Allen Wasp.” Although Gray and Liz went on living and working together, they had drifted apart romantically, Liz becoming involved with the actor Willem Dafoe and Gray taking up with Renée Shafransky, a woman twelve years his junior who worked as the program director for an artist-run experimental-film group called the Collective for Living Cinema.

The next two and a half decades saw Gray’s growing commitment to both writing and acting; he worked for years on a novel called Impossible Vacation (he once described himself as “a Puritan who can’t take a vacation”), which was finally published in 1992, and experimented with new forms of solo work, including an ad-lib piece called Interviewing the Audience, which he went on to refine and perform for the rest of his life. In 1983 he was cast in a role in Roland Joffé’s Academy Award–winning film The Killing Fields, an experience whose impact on him would be reflected in Swimming to Cambodia. He lived and worked with Renée, who became his manager and producer, while continuing to frequent gay bathhouses and have passing affairs. In his journals, he unglamorously recounts his efforts at masturbation (“I went back to Ivan’s to masturbate with little feeling and taking a long time to come—forced”) as well as the ongoing push-pull of his relations with Renée: “I said that I have never been able to dump all my emotions into a relationship . . . and that she had the wrong man if she wanted to be a future-oriented couple.”

As the years passed, Gray’s fame and reputation grew, causing him spasms of guilt as well as occasional pleasure: “Renée, Arthur and I went up to see the Milton Avery show at the Whitney and I got let in for free because I was RECOGNIZED. Little things like that still make my day.” He entered therapy, worried about getting old and fat and bald, did battle with his looming sense of mortality (“Suicide is power over death in that you do it”), and compared himself with other, more successful actors—Dustin Hoffman was a particular sore point. At the same time he lambasted his need for recognition, and feared that becoming more content would lead to his obsolescence: “It seems that I need an audience all the time. . . . I have a great fear of getting well and normal lest I disappear.” He needn’t have worried, since full-fledged happiness didn’t seem to be in his cards. He married Renée in a last-ditch effort to salvage the relationship (“I had to marry her to leave her?”), even as he became involved with a new woman, Kathleen Russo, and continued to suffer the usual “lacerating angst”: “I’m only at peace when I’m on drugs or booze. I don’t know how to go on without screaming. I feel such rage and pain.”

Gray enjoyed some relatively tranquil years during the ’90s and the beginning of the next decade, living as a family with Russo and their two sons, Forrest and Theo, in Sag Harbor. But in 2001, while on a trip to Ireland with his family and friends, Gray was in a car accident that left him permanently in need of a leg brace and with an orbital fracture; when he underwent surgery, hundreds of shards of bone were found lodged in his brain. Despite medication and several stays at psychiatric hospitals, Gray’s habitual depression strengthened its grip, possibly facilitated by brain damage suffered in the wake of his surgery and furthered by his belief that he had made a fatal mistake in moving from Sag Harbor to North Haven. After several failed suicide attempts he finally called it quits on January 10, 2004, disappearing after calling home and talking to his son Theo around 8:30 PM. On March 7, two months of police searching and many sightings later, his body was found in the water off Greenpoint, Brooklyn.

The Journals of Spalding Gray are as intimate—and as skinless—a text as I’ve ever read, full of panic and despair, leavened with boyish misbehavior and dry wit (an ’80s party at the Paris Review editor George Plimpton’s is referred to as looking “like a giant Updike book”) and lit with a kind of disembodied lyricism that honors even the blackest perceptions:

But no . . . really . . . sitting on the stone wall of the pump house overlooking the reservoir eating my old tuna, jalapeno and “hot” hummus sandwich I had a peaceful sense of NOTHINGNESS and that was what I was going to come to. DEATH is NOTHING. It’s not death that’s sad, it’s life. There is nothing sad about nothing. I had a very strong feeling that I am nothing visiting something. Yes, I am nothing visiting something and returning to nothing.

Throughout these pages, Gray seems both very childish and very wise, a small boy chased by furies. “If I continue being who I am now,” he wrote on September 27, 1985, “I see disaster written on the walls.” He continued being who he was, for both better and worse, and disaster—coming at him from both the outside and inside—eventually did catch up with him. “It makes me so sad to be happy,” he observed, with his usual dark clarity. The odd thing is how happy his sadness—exquisitely performed as it was—made us. The water must have been very cold. And the inimitable Spalding Gray, a self-described “un-American original,” is very gone.

Daphne Merkin, a contributing writer to the New York Times Magazine, is the author of Enchantment (Harcourt Brace, 1986) and Dreaming of Hitler (Crown, 1997).