In Alan Hollinghurst’s captivating 1988 debut, The Swimming-Pool Library, the footloose young aristocrat and would-be biographer William Beckwith is consoled by a friend after he learns of a devastating chapter in his family’s history. “Isn’t there a kind of blind spot . . . for that period just before one was born? One knows about the Second World War, one knows about Suez, I suppose, but what people were actually getting up to in those years . . . There’s an empty, motiveless space until one appears on the scene.” Blind spots—familial, sexual, national—have fascinated Hollinghurst in all his work, and few have gone after them with such a surfeit of exacting irony and sinuous prose.

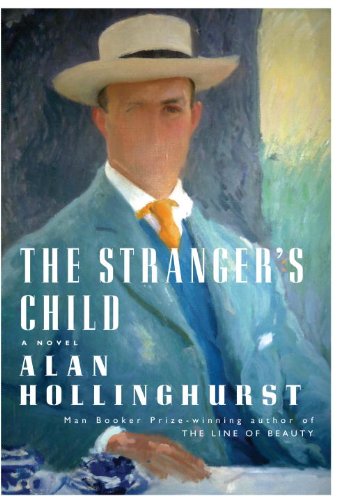

Hollinghurst’s characters are often plunked down on the edge of an era just as it slips into the past, partially aware that they are witnesses to a moment that is disappearing in front of them: His 2004 Booker Prize–winning The Line of Beauty captures the wane of the Thatcher ’80s, and The Swimming-Pool Library pictures gay life in London of 1983, during the “last summer of its kind,” before the wholesale devastation wrought by AIDS. The Stranger’s Child, the author’s fifth novel and his first in seven years, finds Hollinghurst in new historical territory, away from the familiar precincts of the recent past and reaching further back to an England that predates his birth. Yet the good-bye-to-all-that melancholia that tints his earlier work hangs over this sprawling, decades-hopping book from its opening section, which takes place in the summer before Britain mobilized for the First World War.

The novel concerns the brief life and long afterlife of the glamorous bisexual poet Cecil Valance, a raffish young product of Cambridge, “mountaineer, oarsman, and seducer,” in the words of his literary executor, whose hagiographic memoir of Cecil will be dismissed as dated tripe (much like the bulk of the poet’s verse) over the course of The Stranger’s Child. Cecil’s death in World War I catapults his reputation and canonizes the misty odes and patriotic sonnets he left behind, characterized by a later commentator as “a first-rate example of the second-rate poet who enters into common consciousness more deeply than many great masters.” In five sections, each focusing on a different character decades removed from the Edwardian era in which the poet lived and all narrated through Hollinghurst’s mordant, omniscient voice, the novel follows Cecil’s literary reputation across the last century and into the present one, all the way up to 2008, when a used-book seller hunts for a likely lost trove of poems while fumbling with his text messages.

The Stranger’s Child opens with the visit Cecil pays to the Middlesex family of his Cambridge friend and clandestine lover, George Sawle, in the middle of 1913. This, too, is clearly the last summer of its kind, a brief idyll at the quaint Arts and Crafts home of the Sawles (“Two Acres”) before the war will put an end to the entire Edwardian ethos on display, an ethos that the doomed Cecil sentimentally memorializes in the poem he composes during the visit and records as a verse souvenir in the autograph album of George’s starstruck sixteen-year-old sister, Daphne. There he rhapsodizes over the “two blessèd acres of English ground” in flowery strophes that bear a striking resemblance to Rupert Brooke’s prewar Georgian homage to “The Old Vicarage, Grantchester”: “All England trembles in the spray / Of dog-rose in the front of May,” Cecil versifies. Although ostensibly dedicated to Daphne, the poem, as Hollinghurst reveals, leads a more complicated double life.

“Rather like the deep in Tennyson’s poem [‘In Memoriam’],” Hollinghurst mirthfully and somewhat facetiously writes, “Cecil had many voices.” To the public that will come to adore him after he is eulogized by Winston Churchill—just as was Brooke, the World War I poet who shadows Hollinghurst’s fictional creation—Cecil’s voice is a monument to stolid tradition, to “be read for as long as there are readers with an ear for English music, and an eye for English things.” To Daphne and to George, it is something entirely different, and the memory of that 1913 visit remains flecked with a host of wilder associations. Ten years after Cecil’s death, as the family meets with his executor, George

himself felt sick of the poem though still wearily pleased by his connection with it; bored and embarrassed by its popularity, therefore amused by its having a secret, and sadly reassured by the fact that it could never be told. There were parts of it unpublished, unpublishable, that Cecil had read to him—now lost for ever, probably. The English idyll had its secret paragraphs, priapic figures in the trees and bushes.

Hollinghurst’s erudite, stylish, and at times very amusing novel tracks the distance between these various versions of Cecil as his friends and lovers mature, reach old age, and approach their own end, and, as they do, find themselves bird-dogged by a new breed of biographers. Not surprisingly, Cecil’s fate becomes a cipher for the evolving times. In the third section, which takes place in 1967, the stray talk around a birthday party for Daphne includes murmurings about the coming legislation decriminalizing homosexuality and rumors about the intimately revelatory biography of Lytton Strachey that Michael Holroyd is preparing. “Was the era of hearsay about to give way to an age of documentation?” asks the coltish gay bank clerk Paul Bryant, who will go on in the fourth section of the novel to become an intrepid if somewhat doltish literary sleuth and write the life study that will propel a more sexually frank view of Cecil. Dim as he may be, young Paul turns out to be correct, and the latter half of The Stranger’s Child plots his plodding efforts to wrench the “secrets” of Two Acres from the doddering survivors who faintly cling to its legacy.

At one point in The Stranger’s Child, when Cecil’s literary executor demurs at the question of the poet’s ranking by remarking, “I’m a historian, not a critic,” George replies, “I’m not sure I allow a clear distinction.” The sentiment could characterize Hollinghurst himself. A novelist with a historian’s engrossment in the past and a critic’s sensitivity to taste and judgment, Hollinghurst is an aficionado of the English literary heritage, particularly its twentieth-century strain, and his prior works are dappled with knowing references to his forebears and characters who eagerly offer criticisms of Anthony Trollope or are mad about Ronald Firbank. In The Stranger’s Child, that bookish fascination envelops every aspect of the novel. Rupert Brooke, whose posthumous 1914 and Other Poems and Collected Poems sold a staggering three hundred thousand copies by 1926, is only one of the writers who course through the novel; you can lose count of the many others—Tennyson, Strachey, Angus Wilson, John Betjeman—who put in cameos. A more overt influence is the E. M. Forster of Howards End and of Maurice, the gay novel famously unpublishable “until my death and England’s.” Hollinghurst is a marvelous ventriloquist of the period stylings of Cecil and of his brother Dudley Valance, a caustic memoirist who marries Daphne and lives in the grand Valance manor, containing a supine marble statue of the fallen Cecil.

As in his previous novels, Hollinghurst allows his remarkable writerly flourishes on the particulars of architectural detail to animate on the vistas of England, but here, literature is the landscape. Seemingly everyone in The Stranger’s Child has written a book or a memoir or a popular history of England. And the most deftly turned of Hollinghurst’s set pieces in the novel occur in precisely those locales where the legacy of English letters is most batted about: in the cluttered offices of the TLS, where Hollinghurst himself worked for years as an editor, and at an academic conference on the literature of World War I at Oxford, where Cecil’s future biographer Paul is cowed by the sight of Jon Stallworthy and Paul Fussell. As Paul attempts to track down a host of documentary loose ends, he is further unnerved by the news of another writer on the same trail, later identified as a textual critic who will be lauded for his “milestone works in Queer Theory.”

Part of the considerable pleasure in reading The Stranger’s Child is Hollinghurst’s ease in weaving all these literary strands across the ambitious and oddly disconnected structure of the book. Its span covers nearly a hundred bumpy years of literary history, during which the tapestry of “English letters” becomes unraveled and rethreaded to generate unexpected patterns. (Picturing Cecil in 1967, one character ruminates, “If you thought of Rupert Brooke, say, then Valance looked beady and hawkish; if you thought of Sean Connery or Elvis, he looked inbred, antique, a glinting specimen of a breed you rarely saw today.” What would Churchill say to that?) The novel’s breadth accounts for its taxingly overpopulated cast. Minor characters spring forth in later chapters so often that at times one might find it advisable to keep a scorecard and pencil handy.

Perhaps, too, the distance of Cecil and his time gives The Stranger’s Child a less palpable sense of urgency than Hollinghurst’s previous novels. Gone for the most part is the sexual exuberance and explicitness of his earlier work—George and Cecil’s sunbathing interlude at Two Acres is a model of blue rectitude. If anything there’s a primness to the sex here that feels ironically shocking in its blatant modesty. Like the war that leaves its effects but takes place entirely off the page, most of the encounters are left to the imagination. There is nothing naughty about the neatness with which Hollinghurst ties up almost all of his loose ends, a resolution that is almost too satisfying to certain expectations and that makes The Stranger’s Child his most conventional effort to date. So be it. There is a poignancy and a humor that is far from conventional, and a sense of an ending that outlasts the comforts of closure.

Eric Banks is the former editor of Bookforum.