In the first chapter of his exposé on the utter decrepitude of East London, The People of the Abyss (1903), Jack London seeks out those “trail-clearers, living sign-posts to all the world,” in other words, the Cook’s travel agents, known for sending curious and adventurous Britons to “Darkest Africa or Innermost Thibet,” for advice on how to navigate, indeed how to find, the East End of London. ‘You can’t do it, you know,’ said the human emporium of routes and fares at Cook’s Cheapside branch. ‘It is so—ahem—so unusual.” Indeed.

For five years, I was fortunate to call East London home. I lived in a former shoe factory–turned–furniture warehouse that had been reclaimed early in the regeneration game, in the late ’80s. I lived in a neighborhood in Tower Hamlets, which had long been among London’s most polarized boroughs in terms of income disparity. It sat along the picturesque Columbia Road, where on Sundays a centuries-old flower market set up at the crack of dawn.

Jack London, again: “The streets were filled with a new and different race of people, short of stature, and of wretched or beer-sodden appearance.”

Ah, yes: the beer-sodden Londoner. Pub culture runs deep in East London. Near my flat was a gay pub popular for post-clubbing recovery. On my first weekend in London, I awoke to a ruckus beneath the casement windows overlooking the narrow passage joining our building and the pub. Four or five young men, two in tutus, were piggyback racing down the street. On another corner was the Birdcage, which I didn’t brave during the time my husband and I lived in East London. The pub’s habitués were reported to be aligned with the white-supremacist British National Party, though they did have a lively karaoke night. The Nelson’s Head was the “estate pub” around the corner. The Flying Scud, on Hackney Road, near derelict during my stay, was finally demolished and replaced by a Tesco supermarket topped by luxury flats.

Across the road were two tower-block housing estates that were easily 90 percent Bangladeshi—nearly all new immigrants, many of whom spoke no English. A block away was our jolly Pakistani newsagent, Joe, whose wife and school-age daughters wore head scarves (and who hung posters in the shop window protesting the French head-scarf ban of 2004). A few doors down was Vals, a longtime Cockney-owned sandwich shop where the proprietors seemed to have it in for everybody (but especially, it seemed, for American expats like me).

As I quickly learned while we settled in, East London—scrappy, pugnacious, riddled with canals, and the subject of literary love letters and hate mail in equal supply—has been built up, bombed, torn down. Lately it’s been resurrected yet again as the neighborhood hosting next year’s Summer Olympics. It is now home to a handful of fine restaurants, a spate of boutique hotels, and a host of high-end galleries—all sitting cheek by jowl with rough housing estates, homegrown madrassas and masjids, Vietnamese grocers, and Ghanaian-run pubs.

As befits the region’s history and multicultural character, East London’s latest revival has a broad range of sometimes-warring political claimants: The Greater London Authority has held the area all but captive as it’s been seeking to institute its ambitious regeneration plans, while the city’s most recent mayors, “Red” Ken Livingstone and the mop-topped Tory and avid cyclist Boris Johnson, have tried to galvanize residents behind each successive development scheme on their watch.

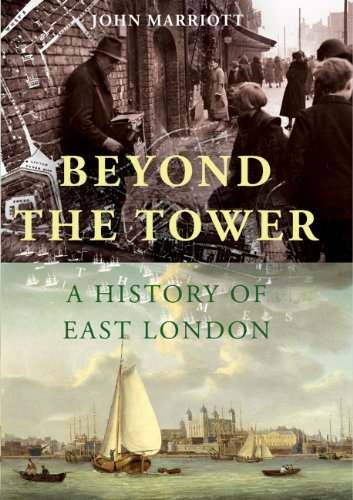

John Marriott’s exhaustive historical survey of East London, Beyond the Tower, covers more than four hundred years of the highs and (many) lows of the area. He reveals what most native sons and daughters have long known: that East London’s rich ethnic, economic, and social history is not a myth but one feature among many in this curious organism’s evolution. As Marriott also notes, the area’s overall growth supersedes any particular narrative thread one might pull together from its broader fabric, be it the confident ascendancy of a new cultural class (e.g., the owners of the exclusive club Soho House, who have opened a branch in the formerly unlikely locale of Shoreditch) or the scheming of greedy developers (as chronicled, convincingly for the time, in John Mackenzie’s 1980 East London film, The Long Good Friday).

Marriott argues that the discrete profile of East London was carved out around 1700. Just prior to that watershed, in the mid-seventeenth century, the area was experiencing its first throes of ethnic and class division, development, and assimilation into the larger metropolis—with the natural boundary of the Thames at one end and the artificial boundary of the rich and organized city at the other.

By 1687, two years after Louis XIV outlawed Protestantism in France, thirteen thousand Huguenots (the vast majority of them silk weavers) had immigrated to London and settled in Spitalfields, on the very edge of the city. They found a ready market for their expertise in the sartorial whims of fashionable Londoners.

By then, London was also well on the way to leading the country into the age of colonial supremacy. The great trading companies—East India chief among them—would eventually make Britain a colonial powerhouse, and along the way would transform London into a world capital. With those larger historical forces in play, Blackwall, located in a cul-de-sac formed by the Thames and Lea rivers, was also undergoing a major shift: Its residents soon found their fortunes or failures pinned to the sweat labor that had come to define East London, particularly in the furniture workshops of Bethnal Green and clothing factories along Brick Lane.

Industry and trade meant population growth, early iterations of real estate speculation, exploitation, and even more immigration: Irish dockhands, lumber merchants from Lithuania, Eastern European Jews (beginning in 1882, after the Russian pogroms), and South Asians. Read one way, Marriott’s book suggests that the perfect storm of labor, class, and racial tension came to overwhelmingly define the East End in one word: poverty.

Marriott’s scholarly account of East London lacks the vibrancy, the vitality, of the actual place. From Wall Street to River Street, it is alive, jumbling, confusing, and endlessly changing—for better and worse. These mercurial, almost block-by-block changes, keep the conversation about the area’s future in play, if not always its history intact. What East London needs—no, deserves—is the Peter Ackroyd treatment.

Ackroyd, the historian and novelist who published the magisterial London: The Biography (2001), winds up revisiting some key episodes in East London’s past as he chronicles the city’s major infrastructure overhauls in London Under. If today’s signature East London development is the ambitious 2012 Olympic Park, many of the region’s past crowning achievements have been underground affairs—which, as Ackroyd makes plain, is also true for the city at large. “There has always been a London world beneath London,” he writes. “There is more below than there is above.” For all the theatrical bluster Ackroyd has cultivated over the years on his history programs for the BBC, there is no denying his unrivaled—if also somewhat entertainment driven—command of the city, aboveground and below.

Ackroyd begins this comparatively concise study by comparing the growth curves of New York and London in socio-geological terms. London’s clay and water foundation, Ackroyd suggests, is making the city sink, while Manhattan’s micaschist allows it to reach ever skyward. He even suggests that the different subterranean and geological profiles of the two cities might “also help to explain the manifest differences in behaviour and attitude between their citizens.”

If Marriott’s book dwells on the socioeconomic, Ackroyd does good trade in the sinister and baleful: Nearly every chapter here strongly elicits the dark, damp, and close atmosphere of the London underworld. Gaseous fumes, bodies from centuries-old mass graves, rats, the threat of the river—a source of fire, biological contagion, and flooding, sometimes all at once—become key points along Ackroyd’s psychological map of London and the Londoner.

He even includes an entomological survey; it imparts, among other things, that a species of mosquito found nowhere else in England, the Culex pipiens, thrives in the Underground tunnels. The biological distinction between these pests and their above-ground cousins is now so great, Ackroyd writes, that the two species seem separated by a thousand years of evolution.

As for the human species, Ackroyd has elevated London’s underground denizens into the heroes of his narrative: the “toshers” of the mid-nineteenth century, who combed sewers for treasure; the mole-men who laid cable for the city’s electrical substations (the most impressive of them still operates a mere forty feet beneath Leicester Square); and the diggers responsible for the first subaqueous pedestrian tunnel beneath the Thames. Indeed, even if one could tell a great-man-style history of subterranean London, its protagonists would likewise be fairly sallow underground men: The great engineer Marc Isambard Brunel (1769–1849), whose unprecedented mining and boring systems paved the way for the London Underground, for instance, or his aqueous counterpart Joseph Bazalgette (1819–1891), whose sewer system under Central London saved the city from the “Great Stink.”

London’s most famous below-grade achievement, in name and deed, is, of course, its transport system, the London Underground, dreamed up by Charles Pearson. As he sought to promote the system as a salve to the congestion on the streets (in the 1830s!), Pearson initially met derision and disbelief. Curiously enough, detractors of the Underground preyed on a now-familiar theme in latter-day debates over urban development: the fear of terrorism. Irish nationalists would unleash attacks on the system, critics warned—and indeed, such attacks occurred with some regularity. Of course, this fear has its modern corollary in the near-simultaneous bombings on the Underground on July 7, 2005. Today, the London Underground’s massive reach (249 miles and 260 stations) makes it one of the most impressive, if also constantly vexed, transport systems in the world.

Though packed full, London Under still manages to seem a little simple. Unlike the powerful engagement he achieved with his subjects in his past urban biographies of London and Venice, Ackroyd at times here seems to treat the book as a laundry list of devilish and dark tales. These vignettes are mainly held together by Ackroyd’s trademark purplish melodrama, stressing the subterranean convergence of covert industry, hidden corners, and weeping tunnels—places, as he puts it, where “enchantment and terror mingle.”

Like Marriott’s study, Ackroyd’s latest book occasionally missteps in conveying an impression of its subject that is greater than the sum of its historical parts; the end result can read as the scraps of his two previous London books rolled into a slightly lumpy whole. But taken together, Beyond the Tower and London Under do succeed in becoming, at least for historically minded students of the city, their own kind of A–Z Street Atlas—the indispensable book-length map that even native Londoners are wise to keep close at hand.

Eugenia Bell is an editor and writer based in Brooklyn, and the design editor of Frieze magazine.