Rock’s accumulated past is accessible as never before due to the Internet’s vast and ever-growing archives. From the most mainstream star to the most obscure lost artist, many decades of music, video, and trivia are just a mouse click or scroll-wheel twirl away from our ears and eyes. It is precisely this unprecedented proximity and vividness of the past in the digital present that makes book-length cultural analysis more essential than ever. The emerging cloud is a messy mass of decontextualized sounds and visuals. Long-form music writing supplies a crucial element of distance and abstraction that cuts through the welter of sense impressions and unmoored information.

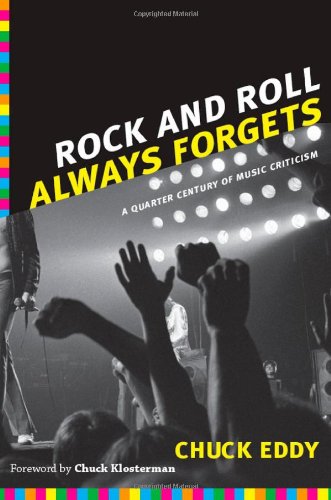

Greil Marcus and Chuck Eddy, two legendary critics with new books, have adopted radically different approaches to the pursuit of rock history’s elusive truths: the iconographer versus the iconoclast. In a 1986 interview, the young Eddy declared that “the thing that bugs me about rock criticism more than anything else, and this applies to both Marcus and [Robert] Christgau . . . is what I would call a hero-worship syndrome.”

Marcus has never been quite as reverential as Eddy made out, but he is interested in making the music he loves seem as important as possible. One of Marcus’s writing tics is deploying variations on the phrase “the stakes,” which crop up whenever he feels there’s something world-historical and momentous at play in a particular song or performance. Of the Doors’ “Take It as It Comes,” he writes, “There’s too much at stake. Too much has been left behind.” Eddy is far less invested in notions of significance and resonance; he’s more concerned with the sheer pleasure of music, which for him includes all the amusement that can be extracted from it, often at the artist’s expense. Eddy’s urge to deride can sometimes seem to override his delight in the music. But it also reflects his reflex to demystify—to bring music back into the realm of everyday life, in pointed contrast to the lofty-minded Marcus’s attraction to the myths that spring up around rock.

Marcus’s books have always combined a historian’s scrupulousness with facts with an alertness to the larger-than-life dimensions of what British critic Nik Cohn once called “Superpop . . . the image, hype and beautiful flash of rock’n’roll music.” As rock’s first self-conscious mythographers, the Doors are such a perfect subject for this approach that it makes you wonder why Marcus waited so long to write a book about them.

Too often in his last decade of output, there’s been a feeling of sinewy strain to Marcus’s prose, like an aging acrobat struggling to pull off the tricks that worked so well before. The Shape of Things to Come: Prophecy and the American Voice, for instance, reached repeatedly for a profundity that eluded the author’s grasp. But last year’s When That Rough God Goes Riding: Listening to Van Morrison, a slim volume on the stout singer from Ulster, showed signs of renewed agility. Now, The Doors is a firm stride toward the recovery of his full powers. Like the preceding book about another mystic-minstrel named Morrison, The Doors is not a rock bio or an exhaustive study of the band’s oeuvre, but a deliberately fragmentary overview that seeks to convey the essence of the band via brief meditations triggered by particular songs and performances.

A long-established Marcus technique is writing about a song as if it were a drama unfolding in real time, as though the band were discovering what the tune is about during its recording. This is fiction, of course: In most cases, songs are written and honed further through live performance long before being taken into the studio, where the band runs through multiple takes and builds up the sound through overdubs until the recording achieves the definitive and polished form that the world hears. Marcus’s odd insistence on treating songs as events rather than constructions can get wearing. The Doors features endless variations on tropes of an “untold story” gradually emerging out of a song. Elsewhere the song is personified: “As the music edged into its seventh minute, it seemed to have developed a mind of its own: you can hear the song musing over itself.” But this overfamiliar approach picks up new credence here, because many of the songs Marcus examines are not studio versions but elongated and improvisatory concert renditions bootlegged by fans. Gathered for official release in 2003 as the four-disc set Boot Yer Butt!, these lo-fi recordings are genuine real-time events: We hear the inebriated Morrison ad-libbing, the band struggling to keep up or pushing the music even further out. Many of these versions document, as Marcus writes, “the drama of a band at war with its audience,” reflecting Morrison’s determination to take the Doors out of the realm of entertainment and turn their shows into confrontational theater.

This spirit matches Marcus’s own fierce commitment to bringing back a sense of rock as an Event, a series of ruptures in History, and rescuing the music from the dead time of repetition and nostalgia. The latter phenomenon is explored in a brilliant chapter titled “The Doors in the So-called Sixties.” It starts with Marcus’s surprise at constantly hearing the Doors on his car radio during the late 2000s and his further astonishment that songs such as “L.A. Woman” had “never sounded so big, so unsatisfied, so free, in . . . 1971 as they did forty years later.” Discussing Oliver Stone’s Doors biopic, Marcus pinpoints the reason behind the media’s obsessive drive to commemorate and revisit the ’60s as “a sense that ever since [then], life had been empty. . . . The anniversaries were attempted funerals. . . . But the funeral never seemed to end, and the burial never seemed complete.” Although Marcus has himself arguably been complicit in this nostalgia industry by authoring several books about Bob Dylan, he writes about his resentment of the baby boomers’ stranglehold on rock history, which has burdened subsequent generations with a sense of belatedness: “Then was when it all happened. . . . You were born at the wrong time; you missed it.” Waiting in line to see Stone’s movie, surrounded by kids in their teens and twenties, Marcus wonders “why they had no culture of their own to rebuke us with.”

In this volume, though, Marcus comes to terms with the idea that the greatest ’60s music cannot be buried and forgotten, because it still feels too alive. Despite the encrusted legends and the attrition of repetition, the rolling majesty of the Doors’ supreme songs and the clarity and mystery of Morrison’s best lines (“learn to forget,” “speak in secret alphabets,” and so many more) ring out with the force of their original newness and nowness. Marcus connects this imperishable potency and promise to specific properties of the band’s playing: “Early on, Robby Krieger developed a way of saying, in a very few, quiet, spaced notes on his guitar, that something was about to happen.”

The triumphant sections of The Doors re-create the sensation of hearing these songs for the first time. There’s a thrilling blow-by-blow account of “The End,” two great takes on different “Light My Fire” performances, and many marvelous evocations of particular passages of playing, from the few seconds of eerie Ray Manzarek organ at the start of “Strange Days,” to “L.A. Woman,” on which Krieger’s guitar is “thin and loose, intricate and casual, serious and quick as thought.”

The closer that Marcus sticks to the music, the better; he draws strength from its inexhaustible vigor. But when Marcus strays, things get more labored and less convincing, as with the meandering attempt to use “Twentieth Century Fox” as a route through Pop art. Ultimately, The Doors is rather like a Doors album, or, more precisely, those five Doors LPs that followed the matchless self-titled debut: killer and filler juxtaposed such that it’s hard to believe the same band was responsible for both.

From 1975’s Mystery Train onward, Marcus has been obsessed with the link between music and history. That connection has lately been severely weakened by the revolution in music delivery systems, with mechanisms such as the iPod shuffle and Spotify insidiously working to erode the divisions between decades and genres. But fans and critics have also actively hastened this process, eagerly rearranging rock and pop history into new shapes, deposing established greats from the rock pantheon and elevating lesser lights. Foremost among these revisionist critics is Chuck Eddy.

The upstart Eddy began his career voicing frustration with baby-boomer elders, including Marcus, who “miss a lot” (meaning, mainly, new music evolving out of the traditions of metal and disco). Reviewing one of Aerosmith’s mid-’90s albums, Eddy jousted again with Marcus, taking issue with the latter’s dismissal of the band as destined to be a mere footnote in rock history. Eddy argued that this was not only condescending to the middle-American masses who raised lighters to songs like “Dream On,” but also ignored the way Aerosmith had anticipated and even contributed to hip-hop (with “Walk This Way”). The spat contrasted Marcus’s belief in the righteous necessity of a rock canon with Eddy’s compulsion—at once moral and temperamental—to deface and contradict that canon at every opportunity.

Near the end of his latest book, sounding sincerely indignant, Eddy rejects his reputation as a contrarian. Still, it’s hard to think of another word to characterize a taste trajectory that’s consistently veered so far from the music that his peers consider relevant and praiseworthy. All critics have pet bands that nobody else in the profession has any time for, but Eddy is a bit like the dotty old lady with forty cats. He’s often way out of alignment with critical consensus, but he’s not a straightforward populist, either. His first book, 1991’s wonderfully heterodox heavy-metal guide Stairway to Hell, snubbed mega-selling mainstays of the genre such as Iron Maiden and Judas Priest in favor of minor figures like Kix and Teena Marie.

Eddy’s eccentricity is not only refreshing and entertaining; it’s also valuable. Whether it’s aberrant taste or simple capriciousness (“Frankly, if I tried hard enough, I could probably convince myself that any tripe was terrific,” he admits in one early piece), something compels Eddy to pay attention to music that no other music journalist can be bothered with. This is a vital counterbalance to the critical herd-mind, and a reminder of how much music making and music fandom exists outside the media radar, and never makes it into the official narrative.

If rock history written long after the event can’t help but be distorted by a hindsight-wise sensibility, collections of music journalism suffer from the opposite problem, as Eddy notes, writing of “the folly of reviewing records in real time, when ten or 20 years down the line might be more reliable.” His dispatches from the front lines of music criticism contain many examples of Eddy being precociously on the money: He notices the shape-of-grunge-to-come stirring in the Pacific Northwest as early as 1986, and celebrates acid house before hardly anybody outside of Chicago had heard of it. But this clairvoyance is sabotaged by a tendency to prematurely write things off. By 1989, Eddy has decided that “all that Seattle crap sounded the same and would never amount to anything.”

Of course, rock writing isn’t really about racing tips. It can, however, be about a kind of prophetic or messianic mode of utterance, whose cadences are thrilling even when you don’t share the writer’s faith. Marcus’s impulse to aggrandize his subjects, even deify them, leads him to godlike music more reliably than Eddy’s impulse to do the opposite: Wisdom trumps wisecracks.

Simon Reynolds’s latest book, Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past, was published this year by Faber & Faber.