Laurie Weeks is a downtown personality from an earlier iteration of New York, a city of late-night performances in Avenue A boîtes and open-air drug bazaars a few dismal blocks away. A vibrant writer-performer, Weeks has enjoyed glints of recognition beyond the demimonde—an (uncredited) role writing the Boys Don’t Cry screenplay, pieces in the 1995 Semiotext(e) anthology The New Fuck You: Adventures in Lesbian Reading and the 2008 edition of Dave Eggers’s The Best American Non-required Reading. For years, though, anyone who knows of Weeks has heard about her novel in progress, the magnum opus, the thing that was eternally about to blow our minds.

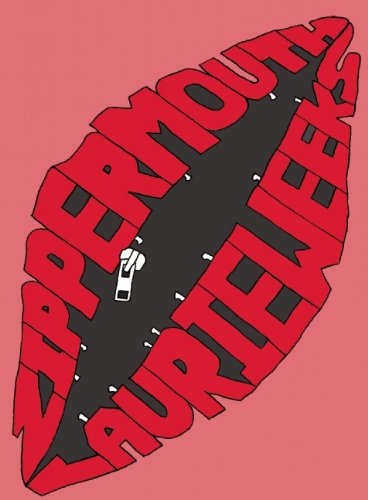

Now, at long last, Zipper Mouth has arrived—and, perhaps suitably for a work so long in the making, it contains multitudes. In this slim, woozy volume of dense prose, one finds letters to movie stars, sidewalk heroin binges, e-mails between friends, and a bravura passage in which a teenage girl writes teeming letters to Sylvia Plath: “How can I be a madly brilliant artist with burning eyes and arms like sticks if I can’t even have a nervous breakdown!”

The narrator is a writer who finds flashes of inspiration in drugs, old movies on TV, and her apparently well-thumbed copy of Living Without a Goal. She spends most of her days hungover in a dingy East Village walk-up, its walls and floors crusted with dried pancake syrup and cat hair. Her answering machine, whose disembodied voices are usually reminding her that she has neglected to show up for a temp-job interview or to pay rent, makes her burrow deeper under the covers.

Her favorite drug buddy is Jane, a straight woman who doles out just enough ambiguity to keep the narrator hopelessly infatuated. The narrator’s desire, so excessively repeated, so doomed to failure, speaks to what is both so aggravating and so important about this book. Readers may well experience an unattainable wish of their own—for the narrator to pull herself together. The first scene of heroin-fueled rapture cuts abruptly to a rehab scene. Oh, we may think, she’s going to clean up. Then the dope-snorting resumes, and we realize that the rehab scene wasn’t a fast-forward; it was a flashback to one of many failed stints in recovery. By teasing us, and frustrating our wish to see the narrator move on—from drugs, from lethargy, from Jane—Weeks skillfully forces us to identify with the protagonist. The deferral of satisfaction also tosses us back, again and again, to the prose itself. Fantastically surprising and convincing images—“the abused mouths of my molecules,” “snickering tangerine suits,” “butterflies of black adrenaline”—are Pop Rocks strewn on almost every page: “I recalled walking, the manic golden night, stars blowing around like jacks in the sky. I was sick with longing.”

Near the end of the book, Weeks’s nonlinearity is given a vivid physical form: “My desires and options are autumn leaves, their leisurely spiral erratic with updrafts and dips, teasing feints and side swirls.” This organizing principle is operative, too, in the dérive-like wandering of the writing, as if the book had been composed in fragments, on different days, different notepads, different drugs. As such, its structure entails a faithful, almost vérité rendering of its narrator’s meandering life.

But there’s something bigger at work in the novel’s refusal of progress, all this basking in time-obliterating bodily pleasure for its own sake. Just in case we’re missing it, Weeks lays it out for us, riffing in fragmentary incantation: “A creative force much like an ongoing multiple girl orgasm, endlessly generative of possibility.” Zipper Mouth, in other words, is “feminine writing” as French feminist theorist Hélène Cixous posited it—a river continually overflowing its banks, untamable, ecstatic. By claiming this lineage, and by wedding deadened dependency to explicitly queer and disordered desires, Weeks has wrung from her long labors a provocative and layered narrative that is much more than just another drug novel.