In his first book, Pavane (1981), David Trinidad included a poem titled “The Peasant Girl,” derived from Charles Perrault’s fairy tale “Diamonds and Toads.” The poet presents an unwanted girl who stoically keeps house for her stepmother until the day she is visited by a hideous crone who begs for a drink of well water; the girl complies, and, for a reward, the crone says, “Whenever you speak, / beautiful flowers and priceless gems shall flow / into the world with your words.” The girl rushes home, anxious to tell

about the fairy and how I had passed her silly test, and as I spoke, a dozen rubies splattered on the wooden floor like drops of blood.

“Keep talking,”

said my stepmother. I did, and orchids tumbled

from my mouth,

and gold coins, and pearl rings, and then

white chrysanthemums,

irises, violets, sapphires, jonquils, carnations, strings of sweet peas streaming as long as my

sentences,

crystal goblets, asters, opals, pieces of topaz,

jade pears.

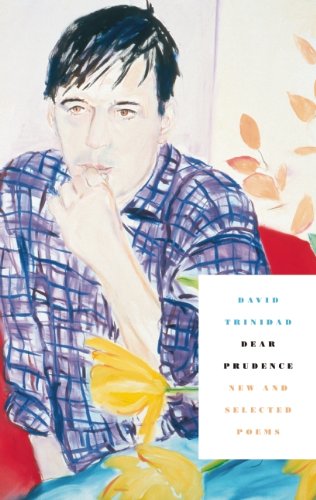

As an allegory for the poet, what could be more desirable than to have such “gifted lips”? Trinidad’s hefty retrospective, Dear Prudence, makes good on this early promise to make poetry extravagant, delightful, and valuable.

This does not seem to be a good time for poems like rubies and orchids, and Trinidad, a resolutely small-press poet, is an anomaly. He doesn’t quite fit in with an avant-garde that relishes the disenchanted and “uncreative,” or with a mainstream that values what critic Stephen Burt (approvingly) has called “the emotional middle range.” As the passage from “The Peasant Girl” makes clear, this poet doesn’t traffic in unconventional grammar or typography—but neither does he specialize in small-bore poems about suburbia. His idea of a “conceptual poem” is “Peyton Place: A Haiku Soap Opera,” written while watching the old show on DVD.

Trinidad’s fascination with pop culture is not ironic or arch. Dear Prudence wears its heart on its sleeve, a heart that is populated by, among others, Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton, Patti Smith and Dick Fisk, Jacqueline Susann and Mia Farrow—and Trinidad’s own family and friends, too, including poets he idolized, like James Schuyler and Tim Dlugos (whose collected poems, A Fast Life, was edited by Trinidad and published earlier this year). Many, if not most, of the performative, ecstatic, and tender poems in Dear Prudence are paeans to twentieth-century icons of page and radio band and screen (Dick Fisk, by the way, is a porn star—and with Trinidad, there’s no need to Google; the poem will tell you everything you need to know). Affectively, these are descendants of Frank O’Hara’s “To the Film Industry in Crisis” and “Thinking of James Dean,” but less wild—Trinidad is a formalist who can’t resist an elegant idea, especially one that organizes nostalgia (much like Joe Brainard’s I Remember). “In My Room” is an anaphora of radio songs he listened to, presented in twenty-four Sapphic stanzas, some internally rhyming. How Trinidad molds fanboy longings into sophisticated forms, dousing them with liberal California light and his own temperamental sweetness, is his secret and his achievement.

Meanwhile, the stylish exercises in Dear Prudence are interspersed with confessional poems that cut to the core. In “Family Portrait, 1963,” the vignettes implicitly trace a pattern of unrequited love to its roots in childhood, with a father inexplicably disappointed in the only people who cared about him. The doomed family romance is a staple of confessional poetry; Trinidad’s innovation is to handle it with a sprezzatura touch worthy of Brainard or Schuyler, and to extend it to the clan of celebrity icons who blow a glamorous breeze through the stale air of the nuclear family. While haikus on Peyton Place might seem less than high-minded, their sincere fun is part of an ethical worldview that permeates Dear Prudence: that people deserve love as well as privacy, fairy tales as well as honesty. Won’t you come out to play is the unspoken latter half of the title, after all.

In fact, the secret theme of Dear Prudence may well be knowledge and its ills. “In a Suburb of Thebes” posits that the speaker is the son who kills his father (Oedipus of Thebes, of course) with his unspeakable gayness (“I admit I killed him . . . the only son he never knew”). “Delphi” begins, “My parents first heard it / from the school psychologist”; the rumor, “it,” is never explained, but it pervades the world until the speaker is even “blacklisted by the stars.” Most devastating of all, “For Nicholas Hughes” opens, “At last we know who / you were . . .” It was written on March 27, 2009, and spoke for everyone who had hoped the beautiful baby in Sylvia Plath’s arms, in the famous photo amid daffodils, would end up safe—and then found out that, a suicide like his mother, he didn’t.

Is Trinidad’s obsession with the Plath story intrusive, like a paparazzo in the trees, like a confessional writing about her kid’s sexuality? Absolutely not: He uses his imagination for sympathetic identification, not titillation. He processes his feelings with fables, and creates crystalline structures for them, like this poem for his mother, “Sonnet”:

The day she died, my mother divided up her jewelry, placed each piece in Dixie cups (on which my father had written, with magic marker, the names of her children and grandchildren): her aunt’s pearls, her

mother-

in-law’s topaz and amethysts, her own mother’s plain gold cross. Earlier, I’d held a mirror while she put on her lipstick (Summer Punch) and ran a comb through

what was

left of her hair. She stared at the gray strands in her hand—not with sadness, but as fact. When she placed the last ring in the last cup, she looked up at me and said, “We never have enough time to enjoy our treasures.”

It’s all there—the family romance, the fairy-tale treasure, and the “magic marker,” David Trinidad. Even in the face of loss, this poet gives us gems, and flowers, and the names of America’s pure products as if they were rare enchanted creatures.

Ange Mlinko is the author of Shoulder Season (Coffee House, 2010).