For much of the past century or so, Mexico has existed out of context.

The Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which ran the country for seven decades, enforced a powerful state of critical amnesia. Newspapers reported news with no background to the story at all. The lives of the powerful weren’t discussed, unless they fell from official favor.

Lately, however, that’s all been changing. Critical biographies of the country’s leaders are published, and read, in a way that was unthinkable as recently as the mid-1990s. Newspaper columnists—Raymundo Riva Palacio, Sergio Sarmiento, Luis Rubio—are essential reading for both the stories that they report and the context they bring to the day’s news.

But until recently, one topic escaped this perestroika-style public scrutiny—the country’s lucrative, violent drug trade.

For years the country’s burgeoning cross-border traffic in illegal drugs existed as background noise. Elements of the PRI had facilitated it, police officers were easily bought off, merchants of cars and clothes welcomed hillbillies suddenly flush with cash—and occasionally a guy from the state of Sinaloa would end up dead in the trunk of a car.

The dope trade, moreover, fulfilled the worst stereotypes that the United States and Mexico held of each other. Mexicans felt the traficantes killed one another and sold their dope to the gringos, so why worry? Americans felt that Mexico was incorrigibly corrupt, so what could you do?

But the past seven years have witnessed Mexico’s descent into ever-deeper levels of hell. Hillbilly thugs have risen from local menace to national threat. Newspapers count not just homicides, but the number of killings with decapitated victims.

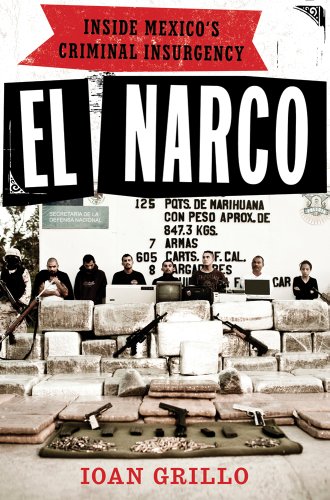

Now, understanding the context of this couldn’t be more important to policy makers and citizens of United States and Mexico. And this is the great benefit of reading British journalist Ioan Grillo’s first book, El Narco.

Several books in Spanish have taken on the task of explaining the terrifying and confusing course of the contemporary Mexican drug wars. But Grillo’s is, as far as I know, the first attempt in English for a popular audience.

Grillo has spent the last few years traveling the regions where Mexico is at war—Sinaloa, Michoacán, Ciudad Juárez—recording interviews with cops and narcos, visiting grave sites and murder scenes.

And as he follows his own dogged reporting and observations, Grillo makes it clear that he’s determined to dig beyond the reigning mythology of the Mexican drug war—just as he’s unconcerned with the accepted wisdom of the pundit classes in Washington or Mexico City.

Grillo follows the evidence, for example, to the important point that the Mexican drug war did not start with Felipe Calderón’s swearing-in on December 1, 2006, as some writers and activists claim. Rather, as the author recounts, the drug insurgency was in full barbaric swing by late 2004 in Nuevo Laredo, and was spreading to Michoacán and Acapulco within a year.

Grillo takes aim at some cherished gringo folk beliefs as well—shooting down, for instance, the NRA’s idea that somehow US guns play only a minimal role in what’s transpired in Mexico. At the same time, however, Grillo well understands how years of one-party rule bequeathed Mexico a deeply dysfunctional government infrastructure and a maimed civic culture, for which the country is now paying a dear price.

He knows, too, that Mexico has to own up to the specific ways that the cartels took root in its native soil. Drug cartels of this scale and power do not exist in America, and they can’t control cops stateside the way they do in Mexico. He’s also seen that Mexico’s drug violence has not spilled over to the United States in any significant fashion, and he says so.

In the United States, he writes, Mexican traffickers “play by American crime tactics, which include the odd murder and breaking some bones here and there, rather than Mexican crime tactics, such as massacres of entire families and mass graves.” El Narco is at its best when Grillo is taking us where few have gone: Humaya Gardens, the narco cemetery in Culiacán, Sinaloa; the Santa Muerte church in Mexico City; and the evangelical wing of a jail in Juárez, among other places.

Grillo veers off course at times. He doesn’t mention, for example, the role of the DFS—the Dirección Federal de Seguridad—the federal agency set up to root out Communists in the late 1940s. On the border, in the hands of appointed thugs like Rafael Aguilar Guajardo and Rafael Chao López, it helped create the plaza system, which broke up the border into regions of control.

El Narco’s prescriptive section would have benefited greatly from a sharper focus on a core problem of Mexico’s: weak local institutions. They are the root of what ails the country. As he launched the battle against the cartels, for example, Calderón had no recourse but to bring in the army because no local police were up to the fight. Indeed, the drug war demonstrates that Mexico needs local reform in every realm: the municipal government, the criminal-justice system, and the schools.

In this respect, Mexico’s drug insurgency serves as an important reminder that local institutions have grown more, not less, influential. Smaller-scaled civic structures are the best arenas for economic development and crime fighting. And in Mexico, the local has always gone begging. In order to change that, the country needs a Congress that is responsive to voters—and that means representatives who are reelectable, as they are not now under Mexican law.

But such oversights don’t detract from the value of Grillo’s study. El Narco achieves something unattempted in the English-language reporting on the Mexican drug war: It lays out in clear terms the contours of a world that has existed for years and only grown more barbaric as it’s graduated to “war” status. Since that world is right next door, it’s high time that English-language readers are able to learn just what makes it tick.

Sam Quinones is a Los Angeles Times reporter and the author of two books of nonfiction about Mexico.