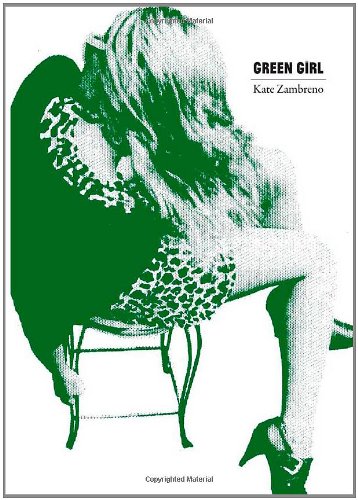

Kate Zambreno resists easy classification. Her fiction squirms under the critic’s microscope like an unruly subatomic particle, appearing first here and there and then in both places at the same time. She crams so much information into Green Girl, her second work of fiction, that I’m tempted to resort to making a list of its various sources and referents, but that would spoil the fun. The book is by turns bildungsroman, sociological study, deconstruction, polemic, and live-streamed dialogue with Jean Rhys, Clarice Lispector, Simone de Beauvoir, Virginia Woolf, the Bible, Roland Barthes, and most of Western European modernism by way of Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project.

OK, so maybe I did resort to making a list, but it really just touches on a few of the stones in Zambreno’s pathway. Green Girl is ambitious in a way few works of fiction are, and it’s certainly more ambitious than the kind of fiction Zambreno is taking on: the single-girl-seeking-not-sure-what-exactly novel that has been pigeonholed as “chick lit” at least since Helen Fielding’s Bridget Jones’s Diary, which Green Girl draws from (its cosmopolitan London setting) and pitches against (its implied self-definition through romance).

Ruth, the book’s titular character is a shopgirl at a large London department store she calls Horrids, which even those unfamiliar with London will recognize as the iconic Brompton Road shop Harrods. She peddles, without much success, a perfume called Desire, a motif Zambreno uses to underscore Ruth’s ambivalent relation to the male gaze: She both wants to be looked at and resents being looked at. “Would you like to sample Desire?” she is taught to ask every customer unlucky enough to pass by her station, though her delivery is so unassured and offhanded that Ruth’s corpulent (male) manager is driven to demonstrate how to sell “Desire” to its target audience of unsophisticated British teens and American tourists. He flatters his victims mercilessly and won’t take no for an answer. It works. He can’t understand why Ruth can’t do the same; she can’t understand why he can’t understand why she can’t.

Nor, at first, can we. An American girl in London, Ruth (the biblical echo is deliberate) is all surface, a cipher in search of its key. One way to describe Green Girl would be as a document of Ruth’s self-decoding, although most of her identity has been picked from the scrap heap of pop culture she consumes in her tiny apartment, which she shares with a raging Id called Agnes (who is, despite her name, anything but lamblike). Ruth and Agnes model themselves after the ingenues of the Nouvelle Vague—Anna Karina, Jean Seberg, Catherine Deneuve—but model is the key word. Their imitations are superficial, whether taken from ’60s French film, or from the pages of Vogue magazine, or from the trashy tabloids Ruth eyes at the corner shop. Zambreno reinforces Ruth’s cinematic obsessions by telling her story in montage, using techniques that will be instantly familiar to fans of French filmmakers like Godard.

Ruth’s superficial longings are rife with subtexts that Zambreno teases out in a variety of ways, even while unsure herself (or at least claiming to be unsure) that there really is any there there. “Are there depths?” asks an authorial voice early on—many such intrusions and voice-overs infiltrate the text from an unreliable cast of directors, spectators, and narrators, all of whom we assume are (some version of) Zambreno herself. “I am still unsure of her interiority,” she writes. “If I prick her will thoughts rush out or just a mess of heavy confusion?” Ruth is a green girl after a quote from Hamlet in which Polonius tells his daughter, Ophelia, “You speak like a green girl, unsifted in such perilous circumstance.” I know this because Zambreno opens almost every short section of her book with an epigraph, and this one appears early on. She means green in the sense of young, and unformed, but also in the sense of vibrant and yearning to grow in some undefined but keen sense that drives Ruth to seek out any and all iterations of that growth. Which is partly about sex, sure (“Would you like to sample Desire?”), but is mostly about exploding the shell of the self by exhaustively exploring every inclination toward debauchery. By the end of the book Ruth has expended her former identity as effectively as, for instance, Julie Christie in Darling (another of the countless films referenced in Green Girl, in this instance after Ruth accompanies Agnes to an abortion clinic).

The accretion of detail and its interpolation with the narrative is both impressive and eventually oppressive, and even contradictory (Ruth’s encyclopedic cinephilia occasionally disappears, and doesn’t always square with a girl who knows literally nothing about literature or art). There are times when Zambreno’s ambition oversteps her still-developing abilities as a writer, when the writing is as clumsy and inarticulate as her main character. But it’s also a tribute to the dizzying whirl of forms and thought experiments on display—and to Zambreno’s brave disregard for mere fluidity of style—that I wonder if the occasional clumsiness isn’t by design.

Her first book, O Fallen Angel (2010), was more focused and single-minded but even more formally unconventional than Green Girl. Though Green Girl, which she wrote before Angel, is clearly not autobiography, I can’t help but feel that some part of its existence owes to Zambreno’s desire to pay homage to the foolishness of someone’s bygone youth. Her affection for Ruth overrides the more squalid and shallow aspects of the story. The reader is left with more hope than despair for Ruth’s future, as she’s swallowed up in a crowd of chanting and dancing Hare Krishnas on Oxford Street and experiences a kind of ecstasis, or stepping outside of herself, which seems like a good place to start moving forward, as the book ends. Wherever Ruth ends up, or doesn’t, there’s little doubt that Green Girl represents a major step forward for a talented and whip-smart writer.

James Greer is the author of the novels Artificial Light (Little House on the Bowery, 2006) and The Failure (Akashic, 2010), and the nonfiction book Guided by Voices (Grove Press, 2005), a biography of a band for which he played bass guitar.