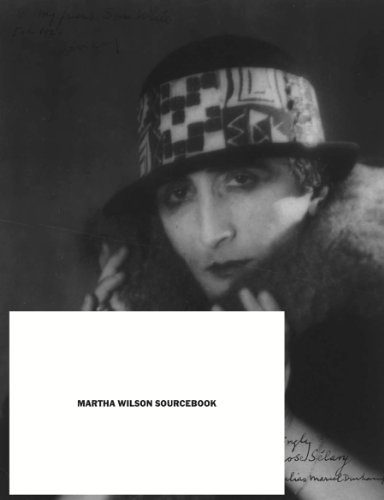

The problem for feminist artists of the past few decades isn’t that their work is absent from museums. It’s that their art isn’t usually where one hopes or expects to find it: in the main galleries of major institutions. However, archives, libraries, and artists’ files richly document art by women—a by-product of these artists’ marginalization from the halls of Great Art, which caused many feminist artists to adopt ephemeral, mass-distributed forms. As testimony to this process, the Martha Wilson Sourcebook, a collection of texts selected by Wilson and reproduced from her archives, performs a double task: It illuminates a chapter of feminist art history, while delivering an idiosyncratic portrait of an important and often-overlooked artist.

The Sourcebook is the first in a planned series of artists’ books published by Independent Curators International, and Wilson, a Conceptual and performance artist with a strong investment in feminist politics, is a fitting figure to inaugurate the series. Since the early ’70s, her work has been about identity as bricolage—a continuous performance of imperfectly juxtaposed, preexisting notions of femininity. In Wilson’s 1974 work A Portfolio of Models, we see photos of the young artist gamely acting out “the models society holds out to me: Goddess, Housewife, Working Girl, Professional, Earth-Mother, Lesbian,” each as a ready-made role that doesn’t quite add up to the woman who takes it on.

Most of the images of Wilson’s own work appear here as illustrations in other people’s writings: The Sourcebook doesn’t give us unmediated access to Wilson’s artwork, or present a linear narrative of influence and “isms.” The few short essays by Wilson (as well as by art historian Moira Roth and curator Kate Fowle), and some reprints of her articles and interviews, introduce a unifying narrative voice into the book. But even with this commentary, the picture of the artist that emerges is largely fragmented and elusive.

Overall, the book benefits from this serendipity, and the unexpected edification of accidental pairings. For example, the pages from a 1975 issue of Ms. magazine, which show Lucy Lippard’s article on “Transformation Art” (including a piece by Wilson about transformation through cosmetics titled I make up in the image of my perfection/deformity [1974]), make a telling counterpoint to a blond California beauty with perfect teeth, taken from a hair-conditioner ad, who appears on the facing page.

The Sourcebook plays up the humor that has always distinguished Wilson’s work—its tongue-in-cheekiness, its bawdiness, its satire, and its refusal to take on the earnestness or solemnity of other political art. This is apparent from the start: The collection begins with a section from Laurence Sterne’s satiric novel The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. Like Wilson’s Sourcebook, Tristram Shandy is a collage, a form of self-presentation through a series of other texts that intentionally scrambles self-portraiture: Sterne’s narrator is so digressive that he doesn’t manage to mention his own birth until the third volume.

The Sourcebook then runs riotously through a range of texts, including some expected feminist classics, as well as a few surprises: pages from Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex; Lippard’s catalogue for the first feminist conceptual art show, 1973’s “c.7,500”; Linda Nochlin’s essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”; Roland Barthes’s Writing Degree Zero; and Angela Davis’s book Women, Race, and Class (the back cover features a photo of Nancy Reagan sitting on Mr. T’s lap). An excerpt from Erving Goffman’s The Presentation of the Self in Everyday Life attests to how important Goffman was for artists such as Wilson, who in the late 1960s and early 1970s were looking for ways to articulate new forms of performance and Conceptual art, reacting against the language-based Conceptualism of the time. The artist Vito Acconci introduced Wilson to Goffman’s writing at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design when Wilson taught English there in the early ’70s. A number of women who worked in performance would eventually become critical influences on Wilson’s self-fashioning—among them a number of feminists—and some, including Carolee Schneemann, Eleanor Antin, and Adrian Piper, make appearances in this volume. But Acconci was one of the few Conceptual artists Wilson then knew who insisted that gender and sexuality should be central to performance-based art. The inclusion of Acconci’s presentation of Seedbed from a 1972 issue of Avalanche magazine marks the significance of this encounter; one wonders, given Wilson’s sly humor throughout the rest of the book, whether she is urging us to see the piece in a new light, instead of the earnest cast of many prior critical assessments.

In the end, the contingency and eccentricity of the Sourcebook’s assemblage prove to be its most intriguing features. This volume—with its sometimes glancing and sometimes obvious connections, as well as the surrounding flotsam of commercial publications (eliciting an immediate sense of the work’s cultural context)—conveys how Wilson thought about her work as it developed over the past forty years. It is more revealing than an artist statement, and more compelling than an assessment of her work by an art historian. The oblique autobiography it offers is an important contribution to the study of feminist art, and a distinctive artists’ book, offering the archives as a salient site for future feminist art.

Aruna D’Souza is associate director of the research and academic program at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute.