Haruki Murakami’s stories are forever slipping from one plane of existence to another. Whether it happens at the bottom of a well (The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle) or atop a Ferris wheel (Sputnik Sweetheart) or through a television screen (After Dark), most of his characters at some point find themselves transported from what they thought was reality to a strange new unreality. But Murakami, for one, would argue that, amid the confusion of our new world disorder, those concepts are not exactly what they used to be. Writing in the International Herald Tribune last year, he wondered, “In an age when reality is insufficiently real, how much reality can a fictional story possess?” Spinning out a thought experiment, Murakami calls our actual world Reality A and the hypothetical world we might have had if 9/11 never happened Reality B. Could it be that Reality A has a “lower level of reality” than the “more rational” Reality B? Is our world less real than an unreal world? And if our sense of reality has fundamentally changed, how does that affect the stories we tell?

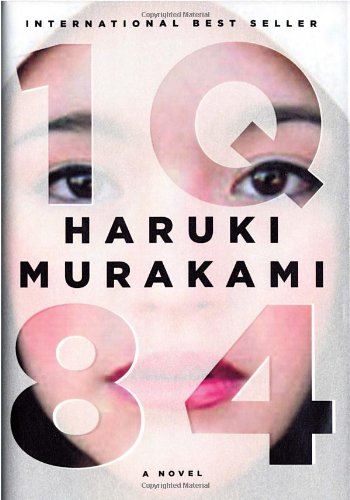

The characters in Murakami’s massive new novel, 1Q84, spend a good deal of time puzzling over the relationship between two realities. One is the Tokyo of 1984. The other is not exactly a parallel world—“You’ve been reading too much science fiction,” an oracular figure scoffs when someone raises that possibility—but a subtly and ominously tweaked variation, the new reality that materialized when the old one “switched tracks.” One of the book’s two main characters calls it 1Q84, “a world that bears a question.” (It’s also a pun: Nine in Japanese is pronounced “kyu.”)

An apotheosis of sorts for Japan’s most popular living novelist, 1Q84 combines the distilled melancholy of Murakami’s short stories and slimmer novels (Norwegian Wood; South of the Border, West of the Sun) with the grand unpredictability of his epic, more self-consciously serious works (The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, Kafka on the Shore). Three books in one totaling 944 pages, it is Murakami’s most elaborate and sustained riff yet on themes he has reworked for thirty years: solitude, thwarted desire, Japan’s (and humankind’s) latent violent streak, the shadow of mortality, the shape of time, the elusiveness of the self, the malleability of reality. His detractors fault him for repeating himself, but repetition and (its flip side) defamiliarization are vital tools in this obsessive author’s arsenal. Transmigrating characters and enigmas, rearranging leitmotifs into new patterns, his stories are paradigms of the uncanny, premised on the peculiar coexistence of the familiar and the unfamiliar. Déjà vu is both the dominant mood and the organizing principle of his work.

The protagonists of 1Q84, Aomame and Tengo, whose stories are told in alternating chapters, are versions of the “ordinary lonely girl” and “ordinary lonely boy” of one of Murakami’s best-known short stories, “On Seeing the 100% Perfect Girl One Beautiful April Morning,” who knew from a young age they were meant to be together and somehow lost each other. As with the adolescent soul mates of South of the Border, it is a single moment that seals their fate as ten-year-olds. Responding to a kind gesture by her classmate Tengo, the bullied outcast Aomame, shunned for uttering prayers out loud (her parents belong to a fanatical Christian sect), reaches out and clutches his hand. This electric, tactile connection marks them indelibly. And then, without exchanging a word, they disappear from each other’s lives for years.

Murakami’s romantic quests are typically first-person accounts of a forlorn male narrator, pining for a girl who has pulled a disappearing act. But in the third-person 1Q84, the quest is mutual: doubled, mirrored, and amplified to cosmic proportions. Tengo and Aomame’s initial attraction is so profound that their long-deferred reunion—at age thirty—calls for nothing less than the course correction of the universe. And while Tengo recalls any number of diffident Murakami everymen, the poised, pensive Aomame is a somewhat surprising creation for an author who has often positioned women as narrative catalysts or male projections: a fully imagined female character with complex desires and a rich inner existence.

Aomame’s and Tengo’s lives have apparently evolved in concert. Both left home and severed ties with their tyrannical families in their early teens, and although hardly celibate (Tengo is seeing an older married woman, and Aomame frequents singles bars), both shy from romantic attachments. Their orbits begin to overlap when Tengo, a math teacher and aspiring novelist, is hired to rewrite Air Chrysalis, a novella by a withdrawn seventeen-year-old girl named Fuka-Eri. This surreal tale of a young girl who lives on a commune and encounters a possibly malevolent tribe of Little People turns out to be inspired by actual experience. Fuka-Eri’s father is the leader of a cult called Sakigake, from which she escaped a few years ago. The book, which becomes a best seller, also takes on a life of its own, and some of its weirder details have a way of leaping off the page and showing up in the physical world of 1Q84, where both Tengo and Aomame have ended up without quite knowing how.

Like Tengo, Aomame has two jobs. A sports-club trainer, she’s also an assassin who snuffs out abusive men for a wealthy widow who runs a shelter for battered wives. Her method, which relies on her preternatural awareness of human musculature, is to delicately stick a tiny ice pick into a point at the base of the brain, an instantly lethal procedure, “as simple as driving a needle into a block of tofu.” Her most difficult assignment to date brings her into direct contact with the dark heart of the Sakigake cult.

Murakami’s longer books often proceed by whimsical, shaggy-dog free association. 1Q84, toggling between would-be lovers, is more streamlined: The horizon point of narrative convergence is also the promised moment of romantic consummation. But while the main action spans a mere nine months (it’s probably not incidental that the time frame is also the duration of human gestation), there are ample flashbacks to formative episodes and primal scenes. And despite the propulsive forward motion, Tengo’s oddball musings on the shape of time—becoming “deformed as it moved forward,” not a straight line but perhaps “a twisted doughnut”—are a clue to the book’s secret structure, which is to be found in the network of cross-pollinating tales within.

As the common memory that has nagged at Aomame and Tengo for two decades pushes its way into their conscious minds and gradually envelops the story, 1Q84 induces a quintessentially Murakamian vertigo—the past seeps into the present, cause and effect become scrambled, and the characters are swept along by forces beyond their control and comprehension. The most potent of these forces is fiction. 1Q84 is rife with stories-within-stories, and some of these stories, once told, can warp reality, or literally change the world. Besides Air Chrysalis, which activates all manner of cosmic chaos, there are bedtime stories, recounted dreams, and, among many literary allusions, nods to Orwell, Chekhov, Dostoyevsky, and Shakespeare. “Town of Cats,” a haunting Twilight Zone–ish vignette (attributed to an unnamed, fictive German author) about a man who winds up marooned in a “place where he is meant to be lost,” becomes a practical cautionary tale for the existentially anxious Tengo. The microfictions planted throughout 1Q84 are like little time bombs, detonating not on impact but later, unexpectedly, as they take on new resonances or intersect with other narratives. More than any Murakami novel to date, 1Q84 is fiction about the power of fiction—a metafictional experiment that has the effect of a spell.

The mutable terrain of 1Q84 may not obey many of the fantasy conventions that govern alternate worlds, but there is a definite rabbit-hole aspect to how we get there. Stuck in traffic, Aomame decides to climb down an emergency staircase off the side of a Tokyo expressway, the David Lynch–like advice of a cabdriver (“Please remember: things are not what they seem”) ringing in her ears. Tengo’s recollection of a day with his ailing father at a sanatorium—vivid but with “touches of unreality around the edges”—is akin to our experience of 1Q84, a place that we, along with the characters, inhabit alert to its shadowy interstices, the passageways hidden in plain sight. Even a teenage girl’s body can, for one stormy night, serve as a conduit between worlds.

The metaphysical key to a Murakami work can often be found in the relationship between its multiple worlds. The alternating chapters in Hard-Boiled Wonderland, for instance, are revealed to be a function of its narrator’s divided consciousness. The most unnerving thing about 1Q84 is that its status as an alternate world remains in doubt—it’s unclear if those around Tengo and Aomame are actually in it, or aware that they are—reflecting Murakami’s apparent conviction that it is increasingly difficult to tell reality from unreality.

Aomame notices a few things awry in the world that awaits at the bottom of the stairs—the cops carry different guns, history has taken a slightly different course—and one glaring discrepancy: a second, smaller, moss-colored moon in the sky. (This, it turns out, is a feature of the world described in Air Chrysalis.) Especially in 1Q84’s second half, with Aomame and Tengo beginning to sense each other’s presence, there is a lot of gazing up at the night sky, and Murakami sees in the moon not just a symbol of change but also, per Yeats, “the most changeable of symbols”: an object of contemplation, a celestial timekeeper, a sign of fertility, a repository of ancient memories, the silent witness (or judge) of all human activity. The notion of a possibly illusory shadow moon also echoes Murakami’s conception of the problems of the self, which is always subject to slippage and division, creating doppelgängers or leaving behind hollow vessels in the process. In 1Q84, an air chrysalis—a womb-like cocoon that the Little People construct out of white threads pulled from thin air—is liable to contain a shadow self known as a dohta.

The free-floating metaphysical intrigue, which also includes sudden-onset hypno-paralysis and numerous instances of telepathy (and one of telekinesis), is rendered in Murakami’s signature style, where the magic seems to be happening between the lines. His laid-back, equivocal voice will never be to all tastes (Geoff Dyer has dismissed it as “low-maintenance, attention-deficit prose”), but it fits like a second skin Murakami’s twin registers of quotidian realism and deadpan fabulism—or, perhaps more to the point, the junctures between them.

In Aomame’s assessment of Tengo’s “deceptively simple” prose in Air Chrysalis, one detects perhaps an immodest autocritique on Murakami’s part. “No part of it was overwritten, but at the same time it had everything it needed,” she notes. “Above all, the style had a wonderfully musical quality.” It’s telling that Murakami has compared writing both to jazz (rhythm, a sense of free improvisation) and to running (a kind of trance state). While his dreamlike moods often emerge from a willful vagueness, he can also describe abstract concepts with an almost perverse precision. Conversations in 1Q84 are freighted with many different types of silence: “a heavy silence having to do with responsibility”; a silence with “all the weight of a sandbag”; an expectant silence, “like a lithograph with no words carved on it yet.” The flow of time is described as “natural, even,” or “like a river approaching an estuary.” Reading Proust leaves Aomame with “a sense of time wavering irregularly when you try to forge ahead.”

As one might expect from an avowed creature of habit, the rigors and comforts of routine remain a cornerstone of Murakami’s fiction even as the cosmology gets crazier. 1Q84 lavishes attention on the simple satisfactions of reading and cooking and eating, on Tengo’s writing process and Aomame’s workout regimen. There is a curious calm and a very human pathos at the center of even Murakami’s most turbulent stories. Magic-realist tales tend to proceed through their fantastical episodes as if nothing out of the ordinary has taken place. But Murakami’s characters cannot help quietly remarking on the extraordinariness of their circumstances, and, more than that, on the sheer strangeness of existence.

This constant imperative—to make sense of things—accounts for (and, more often than not, justifies) the surfeit of explanation in Murakami’s more fanciful works. In its final third, 1Q84 introduces an additional perspective: that of the grotesque yet sympathetic Ushikawa, a misfit detective first seen in The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, who inadvertently helps bring Tengo and Aomame together. As the climax approaches, Murakami locks his characters into a three-way stasis—Tengo tending to his dying father, Aomame holed up in a safe house, Ushikawa on a surveillance mission—and each is left to summarize and interpret what has happened thus far, and to decipher his or her place in the larger scheme.

In the absence of meaning, it is natural to seek comfort in stories, to make them up if need be. This can be fatally dangerous, as Murakami showed in his book Underground, which consists of interviews with survivors of the sarin-gas poisoning on Tokyo subways in 1995 and members of the Aum Shinrikyo cult, which perpetrated the attack. Former disciples talk about living “in a fiction,” and the leader, Shoko Asahara, is called a “master storyteller.” That insight recurs in 1Q84. Equating truth with “intense pain,” the leader of the Aum-like Sakigake tells Aomame, “What people need is beautiful, comforting stories that make them feel as if their lives have some meaning.”

Murakami’s implicit point is that the perils of storytelling do not negate its pleasures. Quite the opposite, they make it more necessary. One way to explain his enormous global popularity is to see him as a novelist with a deep, intuitive understanding of what fiction can still do and what people might want from it today. In the Herald Tribune piece, describing himself as “a hopefully humble pilot of the mind and spirit,” Murakami called the story “one of the most fundamental human concepts,” “a medium of cultural transmission.” Accepting the Jerusalem Prize in 2009, he suggested a political and moral dimension to his fiction: “In most cases, it is virtually impossible to grasp a truth in its original form and depict it accurately. This is why we try to grab its tail by luring the truth from its hiding place, transferring it to a fictional location, and replacing it with a fictional form.” In 1Q84, books are variously likened to problem-solving strategies, maps and manuals that contain “secret code,” and antibodies to a virus.

Murakami’s diagnosis of a world with a reality deficit is precisely the one that underlies David Shields’s manifesto Reality Hunger. But where Shields proclaims the obsolescence of “invented plots and invented characters” in this age of uncertainty, Murakami, who has always had a special sympathy for the traumatized and the bewildered, sees a renewed purpose for fiction. Amid the helpless confusion of a world out of joint, itself an endless source of unsettled narratives, his answer is to fight story with story—to “turn everything into a story.”

The world we live in may seem unreal, but it’s the only reality we have. As the cult guru cautions Aomame, “This is no imitation world, no imaginary world, no metaphysical world.” The characters of 1Q84, some fearing that free will is an illusion, constantly worry that they have opened Pandora’s box, that time is irreversible and deeds cannot be undone, that there is no way back. The book’s big epiphany is all the more thrilling for being a simple sleight of hand, a shift in perspective that reframes the world. Aomame seizes on the potential to control the narrative that has propelled her who knows where. “We create the story, and at the same time the story is what sets us in motion,” she tells herself. Or to put it another way, there can be no action without imagination.

Dennis Lim is a writer living in New York.