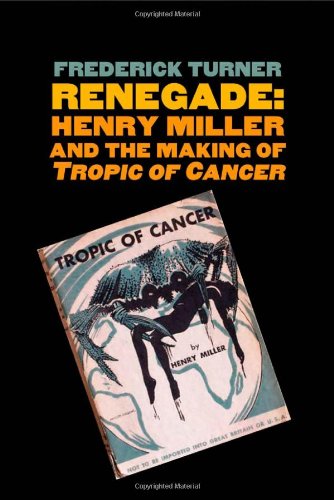

In a letter to his lover, Anaïs Nin, Henry Miller wrote that he was possibly the only writer in our time who has had the chance to write only as he pleased. This kind of hyperbole marked his audacious, pornographic monologue of a first novel, Tropic of Cancer, which was published in the US fifty years ago (after the Supreme Court overturned a quarter-century ban). Now, in Renegade, scholar Frederick Turner reassesses the work, making the case that the book and its author are as quintessentially American as Walt Whitman and Mark Twain. Turner’s volume is part of Yale University Press’s Icons of America series, which covers national treasures such as the Statue of Liberty, the hamburger, Jackson Pollock, Bob Dylan, Fred Astaire, a bunch of other men, and just one gal: the stripper Gypsy Rose Lee. The series aims to tell “a new and innovative story about American history and culture” through these icons, and Turner’s story traces Miller’s mid-twentieth-century ramble back through the dark passages of US history, to the young nation’s “buffalo hunters, backwoodsmen, Indian killers, and outlaws of the hinterlands and urban slums,” claiming that Miller (consciously or not) modeled himself and his books on the American-as-outlaw archetype.

The protagonist of Tropic of Cancer (a doppelgänger for Miller) is an adventurer who, Turner writes, has been sent “on an exploration . . . of the wilderness of the city.” And the urban wilderness Miller discovers inspires the same ugly sentiments that marked those early American explorers—xenophobia, arrogance, violence, and lawlessness. Turner also argues that Miller’s prose is part of a deep strain in American culture that mistrusts highbrow anything, literature especially, but celebrates talk, and loves big talk best: It was not just a fish, but the biggest fish. Or, in Miller’s case: It was not just a cunt, but the biggest cunt. It’s a good story, and it works to make Tropic of Cancer seem more American than ever.

If only Turner could tell as compelling a story about Miller the man. Instead, we get the same old tale Miller told about himself—a caricature of a caricature. Turner tends to portray the novelist’s writing process cartoonishly: “The stuff just poured out as if Miller had hooked a tap right up to the source.” Perhaps there is some truth to that—maybe Miller was on a roll—but the language is lazy. What is “the source,” after all? God? Ambition? Libido? Revenge? It’s an interesting question, one that Miller and his psychoanalyst, Otto Rank, were deeply engaged in. But Turner doesn’t go there. Instead we get: “Maybe it was that his fierce, lonely struggles to make himself into a writer had stripped him not only of his pretensions and illusions but also of his basic humanity, leaving him all writer, all artist.” But it wasn’t a romantic image of an artist—an icon, an “outlaw of the hinterlands”—who wrote Tropic of Cancer. It was a guy who saw a shrink.

Miller once wrote that “art consists in going the full length. If you start with the drums you have to end with dynamite or TNT.” Tropic of Cancer introduces us to his lifelong preoccupation with going the full length into the wilds of being—an inspired mode of living that the world seeks to “crush out” in its fear and hatred of “the miracle of personality,” as Miller put it. Tropic of Cancer’s achievement was how its ecstatic cadences were able to embody the pure joy of being alive, to express an ideal of living freely, without neuroses or cares.

How much more interesting and useful it would be if, now, when we talk about Henry Miller (or any artist!) we commit to “going the full length.” This would mean not paring away the complexity and paradox and humor that makes a human life human, though such an operation is necessary to create an icon. “The standard Miller sets himself” was not, as Turner writes, “heroic and heroically impossible.” It was a vision to aspire to, like any artist’s vision. Henry Miller was a man who wrote word after word while dealing with the pain of a crumbling marriage and the indignities of poverty, and who, like each of us, daily experienced the subtle and inexpressible “miracle” of being. Perhaps to speak of such things is still obscene, but to read how a person navigated the wilderness inside and wrote Tropic of Cancer would be TNT.