It says something about the bewildering reality in the contemporary US that a speculative novelist like Steve Erickson—who has written novels about a dominatrix oracle who makes God her submissive (Our Ecstatic Days, 2005) and a film editor who finds evidence of a primordial scene cached in the frames of a spectrum of movies (Zeroville, 2007)—would spin a variation on the hoary maxim about truth outstripping fiction. In These Dreams of You, Alexander Nordhoc, a frustrated novelist known as Zan, reflects on Bush, the Iraq war, and our black Hawaiian president: “It’s science fiction. . . . Or at least the sort of history that puts novelists out of business.” Insolvency, it turns out, is one of the book’s motifs. Zan is visited upon by a modern-day plague of medical bills, maxed-out credit cards, and an insuperable mortgage note. On top of all that, the local college where he teaches literature and popular culture has just suspended his contract.

Ironically, the only job offer that Zan receives after his dismissal is an invitation to lecture on the “Novel as a Literary Form Facing Obsolescence in the Twenty-First Century”—a vexing topic for most people who care about books, but particularly for a novelist who hasn’t published in fourteen years. Dampening matters all the more, the invitation was extended to him through the auspices of James Willkie Brown, the former lover of Zan’s wife (Viv), after whom the J. Willkie Brown Chair at the University of London was established.

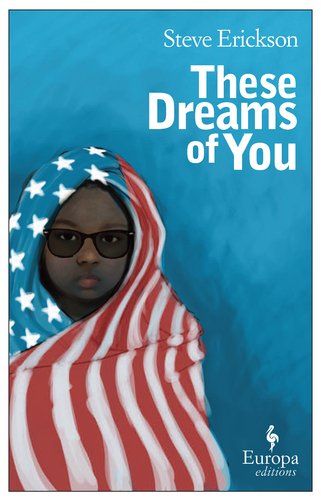

If, by chance, the name James Brown—here a white, British journalist—gave you pause, know then that Zan suspects James became J. out of deference to Soul Brother No. 1 and the famed running back of the Cleveland Browns. Zan has had cause to think about race a lot lately, and not only because of the election of the forty-fourth president. He and Viv recently adopted an Ethiopian daughter, Zema, whom the family calls Sheba on account of her regal disposition. Witnessing his four-year-old daughter’s displeasure at the election results, and recollecting the anxiety that she’s displayed over the incongruity of her skin color with that of her adopted family, Zan worries if Sheba might be on the cusp of developing a complex.

Believing that his daughter will grow up to wonder about her biological parents, Zan supports his wife in her quest to locate Sheba’s mother. Using what scant resources they have, Viv hires an investigative journalist based in Addis Ababa to perform reconnaissance. When Viv fears that her investigation has brought trouble to a woman who may be Sheba’s birth mother, she decides to accompany her family on their flight from LA to London, and from there to make her own way to Ethiopia, where she embarks on a mystical voyage.

In describing the view from the balcony of Viv’s hotel room, Erickson zooms in on two objects that can be read as key metaphors: a figure-eight driveway that abuts a hotel across the street, and the “monumental broadcasting tower, time’s antenna,” that hangs over the city. The figure eight provides a visual analogue for the manner in which details and events in These Dreams of You fold in on themselves like a piece of origami. Events in Zan’s unfinished novel, for instance, begin to occur to him in real life. With regard to the broadcasting tower, harmonics literally radiate from Sheba’s body—so much so that people sometimes think she is singing when she isn’t; thus, Zan’s other nickname for her, Radio Ethiopia. Music is another historical lens through which Erickson explores the intermingling of black and white influences. (Intriguingly, one of the novel’s best subplots involves David Bowie’s possible role in the fathering of the woman who appears to be Sheba’s mother.)

When Zan isn’t thinking about his escalating troubles, his mind is preoccupied by politics. From abroad, he marvels at how quickly the euphoria that attended the 2008 election has descended into rancorous division. Erickson is no stranger to offering up political commentary; his two nonfiction books, Leap Year (1989) and American Nomad (1997), were occasioned by the 1988 and 1996 presidential elections. In “The 9/11 President”—an essay published in the American Prospect that considers the presidencies of Bush and Obama—he wrote, “We’ve always assumed that the America of our dreams is the same place, but it isn’t anymore and maybe never was and never could have been, because in a way distinct from other nations, America is an act of imagination, and imagination never exists collectively; it exists singularly.” Erickson’s new novel builds on these aesthetic politics by making a patriotic inquest into the state, and the spirit of the nation, while evincing an imaginative jouissance by way of its own surrealistic energy.

On a formal level, These Dreams of You pushes against the idea of the novel as a stagnated medium by flexing its own vitality. While Erickson is superb at striking emotional notes, conjuring up historical figures, and ruminating on race and identity, he’s also content to mess around and dabble in the absurd. This mixture of seriousness and irreverence comes off as a salutary proclamation against treating the novel as a precious species that must forever try to look its best or worry about being brushed aside.