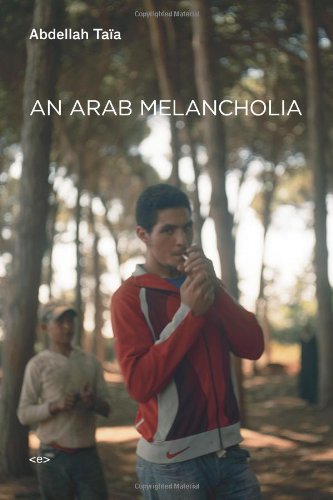

Abdellah Taïa writes short sentences, often without verbs. Single words sometimes. There is light and space in his prose. And despair. At times, he uses the ellipsis suggestively . . . bringing out the apertures within and between words and thoughts, eliciting the unbridgeable gap between individuals. That is where desire seems to lie, and where longing—and melancholia—is to be found in his writing.

An Arab Melancholia is Taïa’s fourth book of fiction, published originally in Paris in 2008. It is his second work to appear in English, following Salvation Army, which appeared in the US in 2009. Frank Stock has translated both works from Taïa’s French originals, and renders the haunting rhythm of the author’s deceivingly simple prose. French is more efficient—verbs imply their subjects—but the experience of reading these books in Stock’s English comes close to capturing the infectious cadence of Taïa’s chain of short sentences.

The distance that remains is not unlike another gap that is impossible to erase, that of a Moroccan émigré translating himself and the conversations of those who have passed through his life into a French language already at a remove from Moroccan experience, even though familiar. That space—that disjuncture—has long been a preoccupation of writers from the Maghreb, from the Moroccan novelist and critic Abdelkebir Khatibi (Love in Two Languages) to the Algerian-born Jacques Derrida (Monolingualism of the Other). Here, Taïa gently lets his reader know that he is translating himself and his experience from the Moroccan Arabic of his youth to the French “script” of his writing.

Though both the French and American editions name An Arab Melancholia a “novel,” it reads like memoir. As in Salvation Army, the protagonist of this short book is a young man named Abdellah Taïa. And the Taïa of the novel resembles the Taïa who has made himself known through public interviews, both in France and in Morocco, where he is something of a literary celebrity and countercultural icon. (The cover of An Arab Melancholia describes Taïa as “the first openly gay autobiographical writer published in Morocco.”) Both Taïas grew up in Salé, the coastal city that faces the Moroccan capital, Rabat, a city known for its “pirates . . . who went around terrorizing people back in the 17th and 18th centuries.”

At the start of An Arab Melancholia, Taïa is twelve years old, living with his parents in a poor neighborhood. The summer heat makes him “crazy and feverish,” as do the older boys who invite him to watch them masturbate, kiss him, or let him join in group sex. Still, Taïa avers: “My childhood wasn’t over yet.” He is seeking “some kind of adventure.”

Taïa’s Salé is claustrophobic, ominous, but also includes the intimate space of the family and the derb, or domestic neighborhood, where the residents know him as the barefooted boy with slightly dirty feet. Taïa has taken the city where Robinson Crusoe was held captive and made it his own terrain. The pirates now are the threatening men of the neighborhood, the “real tough guys. The damned.” These “bad boys” are appealing to him: “I loved them.” But when a group of adolescents abuse him, both physically and spiritually, young Abdellah experiences a profound rupture—he touches a high-voltage power line and, nursed back to life by his father, vows to run toward “the unknown me, the one that was found, the lost self.”

As Taïa’s life unfolds, the retelling of it is not quite the reordering of a life’s experiences to make sense of it as in therapy. Rather, the way he crafts his stories, layering them, coming back to obsessions, is more like a filmmaker’s montage, with flashbacks, voice-overs, and characters who blend into each other. Indeed, Taïa encourages us to see his novel as a film: The ambition to make cinema is what leads him to Paris and, later in the novel, to Cairo, where he participates in another project in exploring the melancholia he sees all around him.

Everywhere, Taïa finds individuals, usually Arab but not always, who are searching to fill in the empty spaces of their lives and to make sense of their memories and passions: Karim, a French-Egyptian filmmaker who travels to Cairo to try to find the father he never knew; Slimane, Abdellah’s Algerian lover, who left a wife and children behind for Paris, but is obsessed with a boyfriend from his adolescence.

These characters, seeking resolutions that are often impossible, are expertly drawn. No matter how painful Taïa’s portraits of friends and lovers are, they are full of empathy, even hope. For Taïa, the feeling of a lack creates a new space in which to imagine a different future—one where melancholia may be a state that can save the lives of a new Arab generation.