When Nell Freudenberger debuted in the pages of the New Yorker in the summer of 2001, the New York literary community responded less to the short story she’d managed to write so much more adeptly than her “Début Fiction” comrades of that year than to the accompanying author photograph, a simple but misguided portrait of a twenty-six-year-old girl staring doe-eyed up at a camera from a curiously vast and purple bed. The reaction was summed up in Curtis Sittenfeld’s 2003 essay for Salon, which offered the riveting thesis that she was simply “too young, too pretty, too successful” and took nearly three thousand words to chart her courageous battle with “schadenfreudenberger.” Something about Freudenberger made people furiously jealous, least of which was her skill as a writer. That first story, later collected in the PEN/Malamud-winning Lucky Girls, was good, as though it deserved an A+ in a creative-writing class, but didn’t quite manage to transcend those rather conventional (teacher-pleasing) boundaries. The same could be said about the other stories in the collection. They were free of the usual pretense and overreaching one expects from a writer her age. She knew the story she wanted to tell, her characters, their environment. She had an assured if slightly detached voice, and the stories were descriptively rich yet so pared down that one might mistake them for interludes between the actual meat of a bigger story. She also insisted on setting most of her stories in India and Thailand, which made for an interesting choice from a bicoastal American whose experience of Asia was limited to a year of postcollegiate travel.

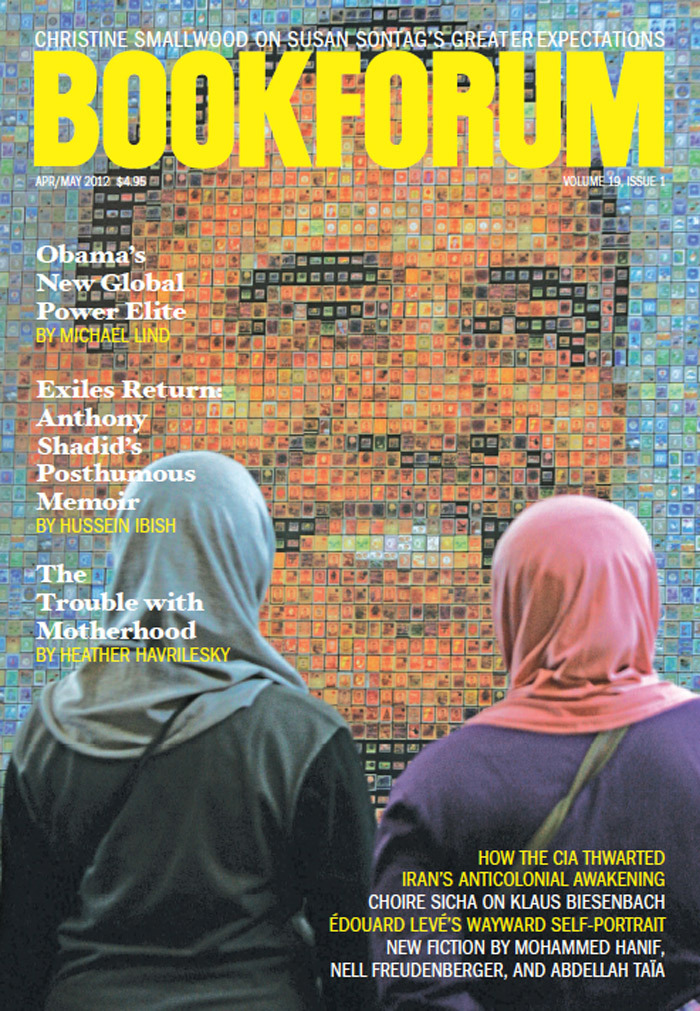

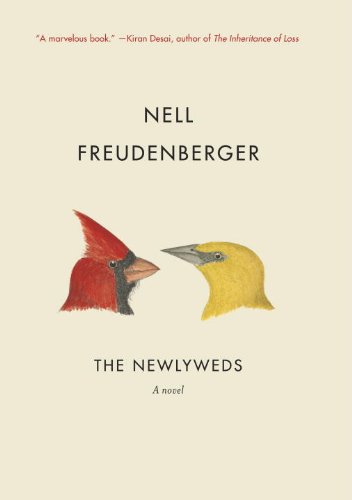

And so she continues in a similar vein in The Newlyweds, her second novel (after 2006’s The Dissident). It is set mostly in Bangladesh, with interludes in the less exotic locale of Rochester, New York. Freudenberger has said that she feels a greater freedom in writing about places she is not as familiar with—“that are closed off in my imagination”—because it allows her stories to unfold more clearly and imaginatively. Though one might also argue that the world she describes in The Newlyweds feels lightly patronizing in all its cultural and ethnic detail—like an anxious postcolonial apology. Freudenberger seems to have no appetite for irony, which may not always be necessary, though her formal reverence for all the correct religious, sartorial, alimentary terminology is a distraction from whatever the story was meant to communicate. More to the point: After I finished the book, I was still unsure whether she had managed to communicate anything at all.

The novel grew out of her short story “An Arranged Marriage,” which was based on an experience she had sitting next to a young Bangladeshi woman on a plane. The woman, Farah, had moved to Rochester from Dhaka to marry a man she had met on the Internet. The conversation appears to have led to a friendship and, later, travel to the Sundarbans, a stretch of tidal jungle landscape in the Bay of Bengal where Farah’s family lived. Finally, Freudenberger was given permission to use parts of Farah’s biography, particularly the circumstances of her marriage, for “An Arranged Marriage,” which ran in the New Yorker in 2010 and would eventually expand into The Newlyweds.

And that is exactly how it reads: less like a novel than an exhaustively detailed 352-page reportage of Farah’s journey. We meet her fictional alter ego, Amina, the beautiful young Desi, as she is learning to adjust to suburban American life and a new marriage to a man she barely knows. We travel back and forth between her childhood and the present, between the variously crammed and filthy quarters that she and her extended family inhabit in Dhaka and the Sundarbans, as well as the new three-bedroom yellow house at the end of a cul-de-sac in Rochester that she now shares with her husband.

Freudenberger goes into minute detail, jotting down not only the contents of Amina’s head, which is filled with some of the twee-est thoughts in literary history (“And what, she was very curious to know, was a hamster?” or “Was there a person who existed beneath languages? That was the question”), but also everything else she notices: numbers (“six hundred and forty-two men with profiles posted,” “her brother Rashid had designed a website and posted 1,678 photographs”), names (in her ESL class there’s a Laila, a Daina, a Jamila, an Abu, and a Pico, none of whom play a particularly significant role in the continuation of the story), clothing (the term “shalwar kameez” is repeated three times in the space of five lines). Everything, it seems, needs documenting, but instead of using detail to enrich the complicated circumstances of her characters or insinuate symbolic relevance, the accumulation of detail ends up polluting the tone with a sort of faux wonder and naïveté, an imagined otherness that allows Freudenberger to revel in her every banal observation. This becomes particularly clear when we see America through Amina’s eyes: “She’d noticed it ever since she’d arrived in America, not only in life but on television. You might cheat, steal, lie, but if you confessed, you could be instantly forgiven—as if the bravery it took to admit it made the thing itself alright.” This is the sort of flimsy observation one can only make if it comes out of the mind of an exotic foreigner.

Freudenberger writes all her stories with a delicious sense of foreboding, a thin layer of disconnect that suggests the world is an enormous dining table and the tablecloth we’re standing on may be ripped out from underneath us at any moment. The trouble is that she does almost nothing with it. Her plots tend to unfold without much specific conflict. Amina encounters a few obstacles along the way to first-world bliss. But even when conflict looms, resolution never seems far away. Amina’s father, who embodies the cliché of the shifty businessman with a heart of gold, is brutally attacked by a violent, grudge-carrying cousin. And then the lifetime of threats he has received is abandoned with the drop of a hat. Most frustratingly, Amina’s main adversary turns out by some lazy authorial sleight to become her biggest champion. Every thing just folds neatly into the next as though the structure of a novel was only ever meant to prop up the occasionally very beautiful details. The inverse would have made The Newlyweds a lot less slight.

Jessica Joffe is an actress and writer living in Los Angeles.