Last summer I was having coffee with a Spanish writer at a café in an upscale Madrid neighborhood just off the bustling Avenida Concha Espina. The thoroughfare is named after an insignificant twentieth-century author who supported Francisco Franco. As my colleague explained with a slight grimace, civic spaces like these were part of the legacy of Francoism, cosmetic but telling. Middling literati such as Espina are memorialized at well-trafficked hubs, while their more accomplished counterparts who ran afoul of Franco’s regime have had their names consigned to remote side streets.

The enmities of the past may have loosened in the decades since the death of Franco—one of the world’s longest-ruling dictators—but they still cramp Spain’s sense of its own history. Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy recently cut funding to institutions tasked with facilitating historical reconciliation—a prelude to the formal repeal of a 2007 law aimed at promoting historical memory of the landmark Spanish Civil War (1936–39) and Franco’s subsequent reign, which lasted until 1975. In spite of renewed international scrutiny, the Spanish Supreme Court maintains that the atrocities committed during the civil war and its aftermath were not “crimes against humanity.” And last spring, the Spanish Royal Academy of History neglected to include the word dictator in its official encyclopedia entry on Franco. A media firestorm ensued, but when the smoke cleared months later, the wording of the offending entry remained unchanged.

Such outbreaks of social amnesia are more common than not; their accumulated effect is to crowd out sober collective reflection and shunt it to the periphery of public life. In part, this is the result of a deliberate political strategy hatched during the country’s transition years, when newly installed democratic leaders embraced reform out of sheer determination not to look back. The other causes stem from the usual scourges of historical memory: mounting partisanship, a new cult of distraction forged online, a younger generation’s weariness with rehashing old grudges.

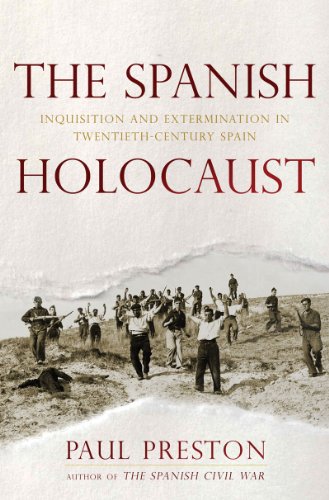

Each well-laid, impeccably researched sentence of The Spanish Holocaust, Paul Preston’s latest book on the Spanish Civil War, stands as a reminder of how Spain’s Fascist past remains an unassimilable muddle; the story is so bloody and horrifying that it’s easy, on one level, to grasp why today’s Spaniards would just as soon relegate it all to a vague memorial blur.

Preston’s basic argument is familiar—and incontrovertible: Franco’s insurgent forces, which sought to topple the democratically elected Second Republic, were bent on systematic terror and extermination of the Left. In the view of the right-wing umbrella party CEDA and the thuggish Falange—abetted by the Catholic Church, radical monarchists, and self-interested landowners—the left-leaning Second Republic, which had been elected to power in February 1936, triggered “the funeral of democracy,” according to agitator José María Gil Robles. Even before the uprising broke out later that year, the Far Right’s strategy was as simple as it was brutal: Ignore progressive legislation passed by the republic, terrorize unions, bait more bellicose leftists into bloody skirmishes, and starve the rural poor by destroying crops and suspending agricultural work. As scores of laborers and children were “found lying in the streets having collapsed from inanition” or “fainting from malnutrition in their schools,” Preston writes, antirepublic insurgents callously coined the slogan “Let the Republic feed you.”

Prior to this, unremitting battles between agricultural laborers and wealthy latifundistas undid the labor market. “It was a short step,” Preston observes, “from the exasperation” of the working poor to “disorder.” In the years before the outbreak of the civil war, right-wing propagandists also ensured that popular economic and social resentments clustered around the ceaseless vilification of Jews, Freemasons, and Communists. There was passionate talk of a “New Reconquista” to fend off perverse foreign elements—even though this appeal was a fairly self-evident bait-and-switch tactic. “Since there were hardly any Jews to be expelled from Spain, it was their lackeys”—in a word, the Left—who “must be eliminated.”

A widespread goal on the right was to “uproot the entire progressive culture of the Republic,” Preston writes. Later on, with the coup in full force, a Civil Guard commander in Cáceres defined the mission of insurgents as “the sweeping purge of undesirables”—a sinister shorthand for indiscriminate killing. The true aims of the nationalist uprising, Preston usefully reminds us, were laid bare in towns like Cáceres and in parts of Galicia and Basque Country. In these regions, resistance to the uprising was generally weak—and the bloodletting was most fervid. As Preston explains, the agenda on high—among Franco and his army cohorts Emilio Mola and Gonzalo Queipo de Llano—was to “educate by terror” through gruesome lessons of “exemplary punishment” modeled after past colonialist tours in North Africa. Insurgent forces often brutalized women in particular—for no other reason than that they felt they could with impunity.

Between the February elections and the July coup, which plunged the country into civil war, Republicans showed themselves all but impotent before this new wave of right-wing militancy. In part, the Spanish Left was the victim of its own ineptitude. But it was also hobbled by a deeply fragmented governing coalition, rife with conflicts among anarchists, Communists, and moderate Socialists. All these destabilizing influences translated into a state of operational paralysis: Early on in the uprising, the Republican government instructed local administrations to confiscate the weapons of its own supporters out of fear that they might imperil security by fighting back. Meanwhile, groups like CEDA, in concert with agents provocateurs from the Falange, incited mounting civic carnage—only to proceed to cynically use public distress over civil unrest to scare the middle class into supporting a coup to restore order. “The undermining of government authority by street violence,” Preston observes, “went hand in hand with the military conspiracy for which it provided the justification.” The republic’s beleaguered prime minister, Manuel Azaña, complained on the floor of the Cortes that under this manipulated climate of fear, Spaniards were succumbing to “a presumption of catastrophe.”

By then the Second Republic and the democratic promise it stood for were a lost cause. The crumbling of the republic’s prospects amid the war’s barely controlled mayhem is the chief subject of this book; Preston contrasts the Right’s coordinated terror campaign with the Left’s sputtering reaction. Both were bloody, though Preston sharply distinguishes the Right’s coordination and preemption from the Left’s ill-fated but haphazard reprisals. As the premeditated violence of the nationalist uprising unleashed mass chaos in the Republican zone, left-wing militants gave in to what Preston calls an “orgy of revenge.” The perpetrators were mostly anarchists (together with some hardened criminals recently released from jail) who formed death squads to kidnap and kill landowners, clerics, conservatives, right-wing sympathizers, and prisoners of war. As Preston writes, “many totally innocent individuals in Madrid were arrested and sometimes murdered . . . for simply owning a business, for having opposed a strike, [or] for belonging to the clergy.” For the most part, Republican officials tried to distance themselves from these vigilante militias, and sometimes to root them out. But on at least one occasion—the notorious massacre of nationalist prisoners at Paracuellos—ranking officials of the Republican-led coalition coordinated the killings.

Whatever remained of that coalition steadily unraveled as the civil war progressed. A mini–civil war raged within the ranks of the Left, among anarchists and Republicans, Communists and Trotskyites. In their midst were also the confidence men and toughs of the fifth column, seeking to accelerate the coalition’s demise from within. For the teetering republic, the uncontrollable violence “undermined [the government’s] efforts to secure diplomatic and material support from Britain and France”—while Franco and his generals were getting air support and arms from the Italians and Germans.

Preston is scrupulously measured and exacting as he sifts through the pillage. His closing chapter on Franco’s postwar repression feels slightly harried by contrast. This is in part a simple function of the book’s scope, which confines itself largely to the horrors of the battle years.

At the same time, though, the story of Francoist terror hardly ends in the early 1940s. After Franco assumed power, he continued pursuing his political foes with trademark vindictiveness. Mass executions were justified by farcical show trials; leftist partisans, union leaders, and bystanders (tried for the Orwellian offense of “serious passivity” in the days of the republic) were herded into concentration camps, in Spain and elsewhere in Europe. Franco raved on well into the 1960s about the Jews, the Communists, and the Freemasons.

Meanwhile, the present-day legacy of Franco’s rule is stubbornly persistent. Lurid accounts of unmarked graves and of children kidnapped from persecuted parents continue to crop up. The country has only recently acquired a government transparency law, which appears to be largely toothless; partisan screeds and outright self-interest sabotage the quality of journalistic information, and the courts still bear the taint of political manipulation. Reading a history as gruesome and bleak as The Spanish Holocaust, it’s tempting to think, as L. P. Hartley famously put it, that the past is another country entirely. But whether the arbiters of Spain’s contemporary political culture want to acknowledge it or not, the past is very much where they continue to make their home.

Jonathan Blitzer is a writer and translator based in Madrid.