Donald Antrim once described the books he spent the 1990s writing as a “more or less related series of novels [that] concern themselves with aspects of American life—small town politics; fraternity and patriarchy; psychoanalysis and sex.” The first novel, Elect Mr. Robinson for a Better World (1993), is narrated by a former third-grade teacher in a small seaside Florida town who entertains Walter Mitty–ish fantasies of becoming mayor while his wife becomes involved with a local cult and the neighbors lay mines, moats, and tiger pits in their finely manicured lawns. (The mayoralty is open because the previous mayor has been recently drawn and quartered.) That book was followed by The Hundred Brothers (1997), in which the titular fraternity gathers at their ancestral estate to “stop being blue, put the past behind us, share a light supper, and locate, if we could bear to, the missing urn full of the old fucker’s ashes.” (No brother can help but be a son.) The Verificationist (2000) is set at a biannual supper for a group of psychologists who practice something called “Self / Other Friction Theory” in a town whose only distinguishing features are a Revolutionary War grounds, a Wicker Beaver Festival, and the vaguely ominous Institute where the psychologists themselves are employed.

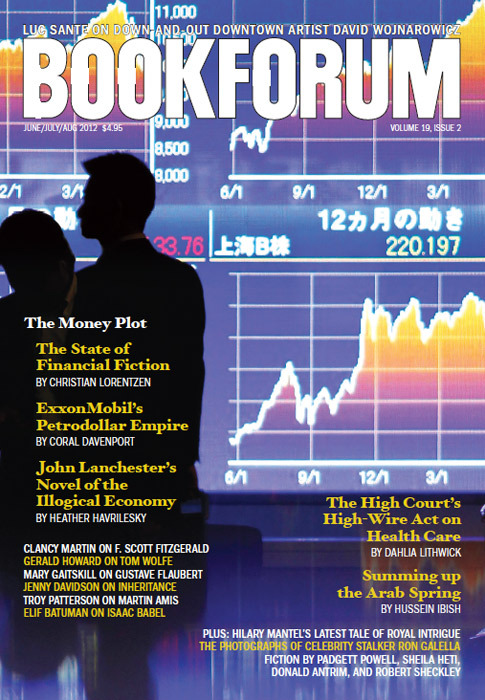

Each book was widely well reviewed upon its publication, and Antrim—one of the New Yorker‘s “20 Under 40” in 1999—was somewhere between a rising and a fixed star in the literary sky. A decade and change later, this is still the case. Since 2000, Antrim has produced a memoir called The Afterlife (2006) and the occasional story or essay, but he hasn’t published another book of fiction. Though it would be wrong to suggest his star has fallen (the memoir was excellent; he remains a New Yorker regular), it must at least be admitted that he hasn’t been much on the tips of tongues of late. Or hadn’t been, until last summer, when Picador reissued The Hundred Brothers with an introduction by Jonathan Franzen, serialized in the Daily Beast, which declared that the book is “possibly the strangest novel ever published by an American. Its author, Donald Antrim, is arguably more unlike any other living writer than any other living writer.” The Verificationist, introduced by George Saunders, followed in November ’11; Elect Mr. Robinson for a Better World, introduced by Jeffrey Eugenides, has appeared this summer, bringing this snappy new uniform edition to completion. A condensed composite thesis derived from the three essays would say, basically: “These books rule!” Which is true. Whether considered individually or in aggregate, these books absolutely, unequivocally, totally flat-out rule.

Which brings us to the question: Just how related are these “more or less related” novels? Although no edition of the books refers to them as linked in any way, and though there are no overlaps in character or setting, reviews and profiles of Antrim going back to the mid-’90s assuredly describe the novels as a trilogy. What they share is a group of crucial tropes: communities—civic, familial, professional—on the verge of collapse; masculinity in crisis, or rather, as crisis; the violence inherent in the everyday; a profound fear of having children (because in a world where all of the above is a given, any prospective act of creation can only appear terrifying and obscene); and, last but not least, a wild, pervasive black comedy that allows you to believe—for a while—that you’re reading absurdist farces rather than existential tragedies.

This seems like a good time to bring up Beckett, and not just because he’s the patron saint of tragic farce (and of loose trilogies). Beckett developed his style by taking a 180-degree turn away from Joyce in order to avoid being smothered by his influence. A generation later, Donald Barthelme, asked why he wrote the way he did, replied, “Because Samuel Beckett already wrote the way he did.” Barthelme’s solution to his Beckett problem was to open his fiction up to a host of nonliterary cultural influences (philosophy, music, painting, pop detritus, etc.), using techniques borrowed from modernism and the visual arts—most notably collage—in a way that made the inevitable fragmentation of his work part of its purpose and effect. Put another way: He evaded Beckett by going back to Joyce’s generation (which includes the Eliot of The Waste Land and the Duchamp of In Advance of the Broken Arm) and using what he found there to reinvent the American short story, which had been largely stagnant since its last reinvention, by Hemingway, in the ’20s. Barthelme’s work is surreal, satirical, disjunctive, and hyper-referential, but there is real emotion smuggled in amid the allusions, laughs, lists, and general weirdness.

For Antrim no less than his forebears, the next step forward requires two steps back, which means that Antrim must evade Barthelme by way of Beckett. (Interiority and character development were Barthelme’s weaknesses—when a heart breaks in his work, it is usually his own.) In Beckett, the mind’s conflict with itself eclipses then erases the outside world, taking us from the walkabouts of Molloy to the hospital/prison room in Malone Dies to the deep inner space of The Unnamable, a soliloquy given by a disembodied voice that desires silence but cannot stop speaking because speech is its only mode of self-knowledge, which is to say proof of life.

There’s an analogous constriction in Antrim’s novels, all of which are delivered as internal monologues by their protagonists. Mr. Robinson takes place over the course of about a week, during which time Pete Robinson moves all around the admittedly small town. The Hundred Brothers takes place over the course of an all-night revel; in a meadow beyond the estate’s walls the fires of a tent city are visible, but just barely, and the brothers and the tent dwellers never interact. The Verificationist covers just a few hours, during most of which time the narrator Tom is physically incapacitated—literally held in place by another character while he experiences something between a dissociative episode and an astral projection, simultaneously trapped both within and outside of himself.

I suspect that The Hundred Brothers is the best book in the trilogy, but Mr. Robinson is my favorite. I’m not sure if this is because I read it first, or because of my own relationship to Florida. (Antrim and I both have strong Florida roots. There’s a scene in The Afterlife in which his alcoholic mother is admitted to Mercy Hospital in south Miami, the hospital where I was born, the year before I was born there.) The Verificationist—set in a pancake house, and largely concerned with a bad psychologist’s paranoid sexual fears and/or fantasies about his wife, his dining companions, and their teenage waitress—is probably the weakest book, but it is also the most daring. It launches from the most ludicrous premise but takes the deepest dive into the abyss, and thus brings the trilogy to its proper and necessary conclusion. (Unfortunately, and unaccountably, Picador has further loosened the loose trilogy by reissuing it completely out of sequence. The correct order is Mr. Robinson, Hundred Brothers, Verificationist.) In Mr. Robinson and Brothers, the threat or reality of physical violence, however objectively brutal, serves a relieving function in that it displaces or ends psychic trauma. In The Verificationist there is no threat of serious violence, and hence no hope of psychic relief.

Antrim’s novels are relentless explorations of interiority and character. His men are fully realized from the moment we first encounter them. Their seamless soliloquies run two hundred pages apiece without chapter or even section breaks, but they’re set in our own world, with its Barthelmean bric-a-brac, rather than in some Beckettian void. The Hundred Brothers begins with a two-page-long grammatically correct sentence in which Doug names and describes all ninety-nine of his brothers; The Verificationist begins with an attempted food fight. Here’s the first paragraph of Mr. Robinson:

See a town stucco-pink, fishbelly-white, done up in wisteria and swaying palms and smelling of rotted fruits broken beneath trees: mango, papaya, delicious tangerine; imagine this town rising from coal shoals bleached and cutting upward through bathwater seas: the sunken world of fish. That’s what my wife, Meredith, calls the ocean. Her father was an oysterman. Of course, that trade’s dead now, like so many that once sustained this paradise. Looking from my storm window, I can see Meredith’s people scavenging the shoreline. Down they bend, troweling wet dunes with plastic toy shovels: yellow, red, blue. The yellow one, I know, belongs to Meredith’s mother. I want to call to Helen, to wave and exchange greetings, but I know she’ll never acknowledge me after the awful things that happened to little auburn-haired Sarah Miller, early last week, down in my basement.

Everything about this is beautiful, from the summoning of Gulf Coast Florida to the artful introduction of two major plot points (Sarah Miller, obviously, but the fish will prove important, too). We immediately believe in Pete Robinson, and are ready to hear whatever he has to say, which is good because he has a lot to say about a lot of things. Unfortunately, in Antrim’s world, all knowledge is destabilizing, and self-knowledge—apocalyptic and inevitable—is the most dangerous of all. It cannot be a coincidence that all three of his narrators are in some sense self-taught: Pete is an amateur scholar of the Inquisition; brother Doug studies genealogy and tribal sacrifice rituals in his enormous family library; Tom is a Revolutionary War reenactor. Like Mrs. May in Flannery O’Connor’s “Greenleaf,” Antrim’s narrators maintain a rigorous obliviousness to their culpability in their own lives—they can see everything but themselves as they appear to others, i.e., everything except the obvious. Unlike Mrs. May, whose world changes in an irrevocable instant, each of Antrim’s men gets a whole book to break or be broken out of his mental shelter/prison by fitful degrees. But the result is the same: The obvious catches up. It catches you right through the guts and heart.

Justin Taylor is the author of The Gospel of Anarchy (2011) and Everything Here Is the Best Thing Ever (2010; both Harper Perennial). He lives in Brooklyn and teaches at the Pratt Institute and NYU.