If David Wojnarowicz were alive today he’d be turning fifty-eight in September. Who knows what his art would look like by now? But there is every reason to think he would have been one of the relative few to have graduated from the hit-or-miss East Village art scene of the 1980s and gone on to greater glory. His stencils, icons, symmetry, hot colors, homoerotic imagery, and street art all remain visible in the work of others now. His ghost is just about discernible around the edges of stuff by Gilbert & George, Banksy, Shepard Fairey, Barry McGee, and I’m sure you can think of more. Of course, maybe if he’d lived he’d have taken several radical turns away from those tropes by now, but in either case he’d surely be getting retrospectives, awards, tributes—the treatment accorded a significant artist in the fullness of maturity. He was that vital, protean, fecund, original, and pioneering in his life and work.

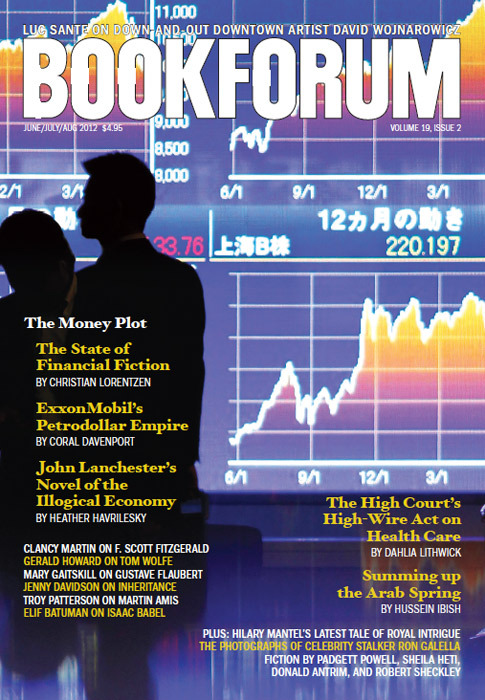

But fate arranged things differently, and today David Wojnarowicz is primarily famous for being dead. Unless, that is, he’s more famous for serving as a convenient bogeyman and target for the Christian arm of the American right wing. Wojnarowicz contracted HIV in the late 1980s and died of AIDS in 1992, and in his last years he did not mince words when it came to the government’s criminal negligence, with the active complicity of most of the Christian churches, with regard to the disease. He remains as much alive to the right wing as he does to his admirers, but what ostensibly inflames his enemies are not his accusations. On December 1, 2010—World AIDS Day—the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, capitulated to demands by the Catholic League and pulled Wojnarowicz’s work from the show “Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture.” At stake was an eleven-second sequence from his film A Fire in My Belly (1986), which showed fire ants crawling over a crucifix. They also crawled over watches, coins, and other items—the symbology was not subtle, but it probably wouldn’t occur to most people to consider it blasphemy, either. Although it’s quite possible that the sequence could have raised the ire of the league’s William Donohue, a sort of comic-opera Grand Inquisitor, had it been made by Joe or Jane Blow, the fact that it was the work of Wojnarowicz predictably evoked the cordite aroma of the Culture Wars, when people like Donohue made their names and their talking-head profiles. To those cartoon cowboys, Wojnarowicz, Karen Finley, and Andres Serrano were the Dalton Gang, and even in death his name can still cause their trigger fingers to itch.

And Wojnarowicz more than the others represented everything the Religious Right wanted to erase from American life. He represented gay pride at its most intransigent and least bourgeois; he was open and unapologetic about his past as a teenage hustler; he enjoyed provocation for its own sake, well before it took on urgent political significance. And he was an artist and writer who was entirely self-created, owing nothing to the academy or the art world of his time, and who spoke directly to an audience of his peers, like a rock star. He wasn’t the only artist of the ’80s to manage that, but Jean-Michel Basquiat had been absorbed by the high-hat galleries and Keith Haring’s imagery was endlessly recuperable, so that their radicalism was to a degree blunted. Wojnarowicz was accessible, charismatic, articulate, and blazingly angry. He had the potential to reach beyond his Lower Manhattan planet of the like-minded and reach into teenagers’ bedrooms across the land. Even if that exact train of thought did not present itself to Donohue, Donald Wildmon, Jerry Falwell, Jesse Helms, and their ilk, they could nevertheless glimpse its outline. Wojnarowicz was a threat.

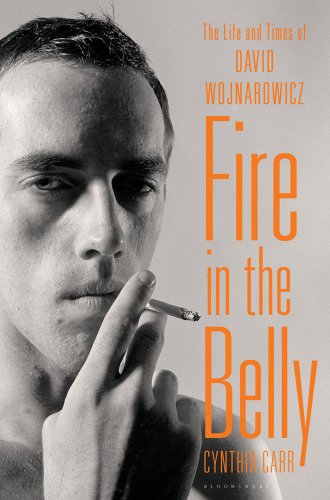

What galvanized his anger, obviously, was AIDS and everything that accompanied it, but it had been simmering within him for the better part of his life. His childhood was traumatic, to say the least. Sometime in September 1954, his father, Ed, an alcoholic who had gambled away his salary, brandished a gun and threatened to kill his wife, Dolores, and their children. David was born on the fourteenth, but it is not recorded whether the incident occurred before or after that date. The parents were divorced a few years later, although that hardly improved matters, as David and his older brother and sister were swung back and forth between them in a ceaseless drama that involved threats, beatings, abandonments, and even a kidnapping. Both parents were wildly unstable, Dolores in her quiet way not much less so than the violent and dissolute Ed, who killed himself in 1976. In the accounts assembled by Cynthia Carr in her new biography of Wojnarowicz, Fire in the Belly, Dolores appears passive, recessive, often emotionally absent, not to mention passively aggressive and extremely unreliable. (She is still alive, although she did not respond to Carr’s requests for an interview.) It is telling that the three children—Carr had interviewed David late in his life on a number of occasions, in addition to talking to his siblings—could seldom agree on details from their childhood, were given to significant memory lapses, and habitually misdated their own recollections. A diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder would not appear out of the question for any of them, including their mother.

In general, biographies provide the reader with two patches of tough sledding: the childhood of their subject, which is usually sketchy, haphazardly documented, and sometimes stultifyingly dull, and tends toward the generic; and the years after fame has come, which most often resolve into mere lists of addresses and other famous names. In the case of Fire in the Belly, the latter phase is, of course, conspicuously absent, and the former is gripping and very much of a piece with the balance of the life. This is a reflection not only of Wojnarowicz’s extraordinarily difficult existence, but also of Carr’s doggedness and resourcefulness as a reporter—not to mention her wisdom, taste, and writerly skills. In addition to working out a plausible account of his childhood from piecemeal clues, she manages to document his adolescence with a thoroughness that makes the book one of the most vivid accounts of teenage creative development I’ve read yet.

This too is made possible by the reconfigured timescale of a short life: Every year lived becomes in retrospect proportionately longer and more full. If somehow Rimbaud had lived to a ripe old age, do you think that more than a handful of scholars would be bothering with his Latin school verse? But then you can’t quite imagine Rimbaud reaching even his terminal age of thirty-seven, which is also how long Wojnarowicz lived. And how easy is it to imagine him in middle age or beyond? The particular energy that connects his works in diverse media is emphatically young, even when he was ill and slowing down. You’ll note that well before anyone had heard of AIDS he was working on his extended “Rimbaud in New York” series, photographs of various young men wearing a mask of Rimbaud’s face as photographed by Étienne Carjat, posing in significant locations: Forty-Second Street, the meatpacking district, the subway, the West Side piers, where men met for sex. When someone dies young, everything comes to look like an omen.

In 1971, at sixteen, Wojnarowicz moved out of his mother’s West Side apartment and went to live on the streets. He had already tricked a few times and now started hustling professionally. That is a standard feature of his legend, and it is true, although the broader truth is as complicated as adolescence usually is. He lived on the streets, in a halfway house, in a squat, periodically at his mother’s and sister’s houses, and in legitimate apartments with roommates. He tricked, and bummed around on the road a bit, and worked at Pottery Barn and in a bookstore, and hung out with people who issued mimeographed poetry zines. The feral aspect of Wojnarowicz’s character coexisted harmoniously with the profile of an artistically inclined urban youth in his path through the 1970s, from uptown to downtown, poetry to bands to Super 8 to art, the progress of an entire microgeneration. (I was born the same year as him, lived a few blocks from him for over a decade, knew many people in common, hung out at many of the same places, but somehow we never met. It happens.)

Things truly started happening for him around 1980. It was then that he formed the band 3 Teens Kill 4 with his friends, and also that Sounds in the Distance, a collection of imaginary monologues he attributed to an assortment of street people, was published in London; he later made it into a play. He worked as a busboy at Danceteria and the Peppermint Lounge and hung out heavily—it was also the year that Club 57 and the Pyramid Club institutionalized gay-straight socializing on the Lower East Side. And around then he met the photographer Peter Hujar, twenty years his senior. The two were occasional lovers, but their relationship was more paternal-filial, or maybe fraternal. Hujar was an artist of the first water, with rigorous standards he passed on to Wojnarowicz; he was also a bohemian of the old school, intransigently committed to voluntary poverty as a consequence of resisting an impressively broad range of pursuits that could be construed as selling out. He exerted a powerful and lasting moral influence.

Wojnarowicz—who had for some time been stenciling vaguely political images around on the streets, most famously his iconic burning house—took his first steps in drawing and painting at the piers, crepuscular ruins with vast expanses of crumbling walls crying out for embellishment, beginning gradually at the well-trafficked Pier 34 and eventually taking over the hazardous, decaying Pier 28 with his murals. His timing was impeccable—in 1982 the East Village art boom was on, an efflorescence of galleries ranging from slapdash to slick (there were eventually 176 of them, although not all at the same time) that seemed to proliferate overnight and faded almost as suddenly. It seemed like everybody who’d been in a band the previous year was now having an opening. The scene was an assortment of wet stones on the beach. René Ricard summed it up pithily at the time: “The feeling of new art is fugitive, like the FUN

Artists could make a name for themselves in very short order—for instance Wojnarowicz, who “between the end of 1982 and the end of ’83 . . . had three one-man shows at three galleries . . . while also participating in fourteen group exhibitions,” not including his ongoing pier project. He was painting on driftwood, garbage-can lids, supermarket posters. His imagery alternated between homoerotic scenes and purposeful emblems, like the pictures on lotería cards: globes, animal skulls, burning children. He was a hot ticket, his works flying off the walls—which didn’t necessarily mean he was being paid commensurately, since the galleries had no backers and tended to run like Ponzi schemes when they weren’t being fleeced by their clients, who might not take them seriously enough to pay their debts. Wojnarowicz realized the irony that his success was owed at least in part to the relative flatness of the surrounding landscape—the scene’s excitement derived from what Brian Eno dubbed “scenius,” not so much individual genius. He told Dennis Cooper that “his success was destroying him because he couldn’t reject it in good conscience.”

While all this was going on, AIDS was gradually taking hold of the city, and Carr punctuates her story with an ominous counterpoint of incidents and dates. The New York Times story headlined “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals” ran on July 3, 1981. Larry Kramer published his call to arms, “1,112 and Counting,” in the New York Native in March 1983, and a few months later the incomparable Klaus Nomi died. In April 1985, Cookie Mueller could still tell readers of her health and advice column in the East Village Eye not to worry about AIDS: “If you don’t have it now, you won’t get it.” (She was to die of it herself four and a half years later.) But the toll was mounting inexorably; no treatment was available, just a menu of “holistic” placebos, mostly involving diet. Hujar was diagnosed in January 1987; by then there were more than thirty thousand cases in New York City. He died in late November, and Wojnarowicz was diagnosed the following spring. By the fall he had started making work that directly addressed the crisis. He had photographed Hujar on his deathbed, and he silk-screened the image onto canvas and laid over it a quote from an official in Texas: “If I had a dollar to spend for healthcare I’d rather spend it on a baby or innocent person with some defect or illness not of their own responsibility, not some person with AIDS.” From then until the end of his life, his work came so fast and was so highly charged it could look as if the disease had actually rekindled him rather than gradually draining his energy.

Under AIDS, the late ’80s and early ’90s were a kind of war; someone compared it to the first battle of the Somme, which decimated the young male population of Britain in just twenty-four hours. And the vast losses were aggravated by the inaction of the government and the murderous contempt of the soi-disant Christians who blamed the victims. Many of Wojnarowicz’s rants may now sound crude, adolescent, ineffective in their scattershot rage—fantasies of torching Jesse Helms, or his calling Cardinal John O’Connor a “fat cannibal from the house of walking swastikas”—but in their time they were not only understandable but necessary, expressing out loud all the stuff people were thinking but mostly kept to themselves, and that is one of the things that art is meant to do. Furthermore, his rage and its public manifestations were probably tonic—to the extent that anything could be tonic under the relentless advance of the disease—forestalling mere despair and collapse. He kept a schedule of work and travel that would have been grueling even for someone in the pink of health.

In his book Close to the Knives, published in his last year, Wojnarowicz considered memorial rituals, and suggested that the most appropriate expression of grief for victims of AIDS would be for the survivors to “take the dead body and drive with it in a car a hundred miles an hour to Washington d.c. and blast through the gates of the white house and come to a screeching halt before the entrance and dump their lifeless form on the front steps.” He died on July 22, 1992. Four years later his partner, Tom Rauffenbart, in the course of an ACT UP action, threw his ashes over the fence onto the White House lawn. Wojnarowicz was a gifted artist who was denied the satisfaction of achieving artistic maturity, but in the face of great odds he seized the chance to become an actor in history. Carr’s book is unimprovable as a biography—thorough, measured, beautifully written, loving but not uncritical—as a concentrated history of his times, and as a memorial, presenting him in his entirety, twenty years dead but his ardor uncooled.

Lucy Sante is the author of Low Life (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1991) and Kill All Your Darlings (Yeti, 2007).