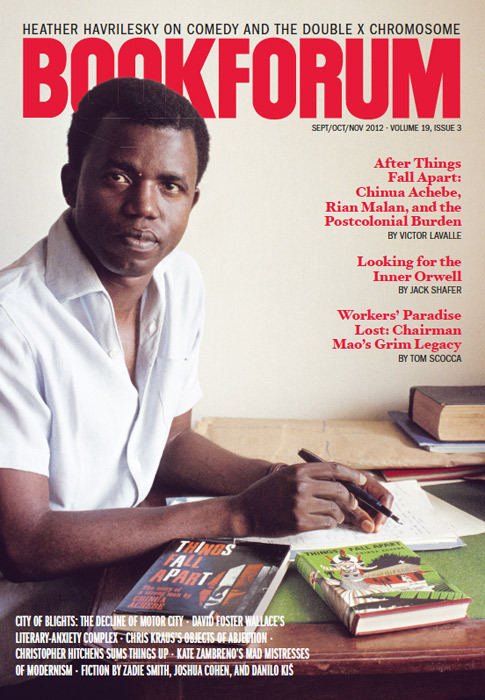

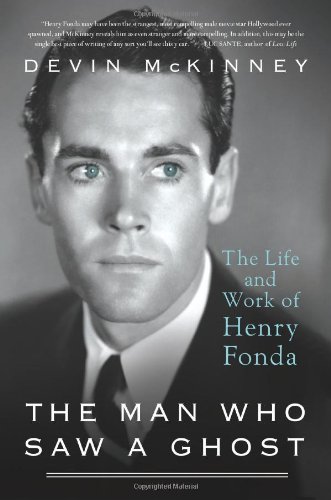

So much of what we know about actor Henry Fonda derives from the authority of his body on-screen: a long, taut, calibrated instrument, most expressive when restrained—as it nearly always was. A lean six feet one, he had the height and physique of a movie aristocrat, but could play a proletarian or a president. Most of all, he always conveyed that, at heart, he was a homegrown American, Nebraska born, in touch with social proprieties but also with the urge to light out for the territory. He perfected an understated style that might be called precisionist, his performances akin to the sharp lines and edges of a Charles Sheeler painting. In 1962, Andrew Sarris wrote that Fonda was “our most truthful actor,” and surely this impression owes something to Fonda’s honest physicality, the way his body commands the screen without appearing hypervirile. His bearing suggested something like morality, a sort of ethics of posture and gait: upright and humane, empathic if also stoic and withdrawn.

On film, he repeatedly bears the values, and burdens, of civilization. He stands up to the lynch mob in the most memorable scene of Young Mr. Lincoln (1939) and in a lesser encounter in The Return of Frank James (1940); he brings order to lawless Tombstone in My Darling Clementine (1946), and stares down bigotry and bloodlust in the sweaty jurors’ room of 12 Angry Men (1957). Elsewhere he is society’s victim, as when buffeted by the effects of merciless capitalism in The Grapes of Wrath (1940), or fed through the modern judiciary machine when falsely branded a criminal in Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man (1956). His late-career turn as the sadistic villain of Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) plays so deliriously against type that his portryal inevitably brings to mind the established Fonda image of straight-backed rectitude. Though far from the whole story, the most lasting picture of Fonda the screen actor—as it exists in the popular mind a full three decades after his death—is suffused with decency and the classic liberal’s sense of conscience.

Yet how vivid is Fonda in our collective consciousness? Many people under the age of fifty associate him not with the performances of his Ford-era classics—young Lincoln, Tom Joad, Wyatt Earp—but with his self-portrait as flinty father in the sentimental 1981 drama On Golden Pond. The dearth of books about him may be less a result of critical neglect than a sign that he has long been receding from us. Because his two biological children are linked to ’60s counterculture via hedonism (Peter on his motorcycle, Jane as intergalactic sex kitten) and leftist radicalism (Jane in Hanoi), and because each had a publicly strained relationship with him, we see Henry as a man borne only so far along the currents of history, and then stranded. The intensities of familial strife, amplified into cultural conflict, make Fonda—the outmoded liberal, the vital-center moderate who is too accepting of compromise—seem marooned on the far side of the 1960s.

Into the void of writing about Fonda comes Devin McKinney, whose previous book, Magic Circles: The Beatles in Dream and History (2003), considered a subject whose cultural centrality is a given. The aim of McKinney’s new book is to consider Fonda as a figure worthy of the same treatment, despite his waning presence in the American mind. It is both a biography and an often-brilliant feat of criticism. McKinney paints Fonda as a performing artist who continues to matter because of his lifelong reckoning with the darkest recesses of American history: “We’re encouraged, by our cultural heritage as much as our leaders, to forget the past. But Henry Fonda acts as if he has never forgotten anything.”

One is always aware of McKinney’s hand shaping his material. Two crucial events—Fonda’s witnessing of the lynching of the black laborer Will Brown in Omaha when Fonda was fourteen years old, and his two possible suicide attempts in the fall of 1935—are told out of chronological order, withheld to create maximal resonance in the narrative. McKinney tells Fonda’s story in the present tense, and now and again calls his subject “our man”; such breezy gestures are perhaps meant to offset the grandeur of some of his claims. In McKinney’s telling, Fonda is haunted on a large, even mythic, scale. He comes across as a priest of remembrance: Fonda “cannot imagine living without a responsibility to the dead”; “when Fonda invokes a responsibility to the departed, it is something very close to a statement of soul.”

But what of the man’s life, its contradictions? “His conflicts made him a cold, cussed, altogether baffling and fascinating man,” McKinney writes. Fonda was by all accounts a difficult person, driven in his work but emotionally remote, a control freak given over to explosive outbursts. Rage was “a basic component of Henry’s character,” we are told. Its origin is fairly mysterious. McKinney attributes Fonda’s temperament to his Christian Scientist upbringing (a faith he did not practice later in life), and to his father’s likely struggles with depression. Still, young Henry enjoyed a “lemonade dream of American childhood” in the Omaha suburbs, apparently free of family discord, though witnessing Brown’s lynching doubtless exerted far-reaching effects on him.

Only in the 1930s, as Fonda’s career was taking off, does the darkness that haunted his life begin to be made visible. His friend the actor Aleta Freel took her own life in 1935, as did Freel’s husband, Ross Alexander, the following year. Thus began the succession of suicides that hounded Fonda, including those of Thomas Heggen (possibly an accidental overdose), whose 1948 adaptation of his novel Mister Roberts was one of Fonda’s theatrical triumphs, and of his first wife, the actor Margaret Sullavan, decades after their divorce (they had remained friends, and often lived close to each other). These deaths are satellite events that circle the cataclysm that struck Fonda on April 14, 1950, when his second wife, Frances, mother of Jane and Peter, slit her throat with a razor she had smuggled into the Craig House sanitarium in Beacon, New York. Fonda was then seeing Susan Blanchard, the woman who became the third of his five wives. He was excised from Frances’s will, and was not included among those for whom she left parting notes.

Although Frances’s suicide occurred after many of Fonda’s finest performances, McKinney suggests that the death defined Fonda’s career, wrenchingly corresponding to a sense of doom, “the dark shape in Henry Fonda’s screen life,” that had swirled around roles such as the angry Dave Tolliver in the early Technicolor drama The Trail of the Lonesome Pine (1936) and the condemned convict Eddie Taylor in Fritz Lang’s You Only Live Once (1937). Frances’s death becomes the key to unlocking Fonda’s middle-aged volatility and restlessness, qualities that make him continually intriguing despite an acting résumé that is lurchingly uneven. How else can we explain Fonda’s interest in roles (generally for the stage) depicting suicide? In an era when he could, and did, mint money as an advertising spokesman on television, he nonetheless embraced the grueling lead role in Garson Kanin’s play A Gift of Time (1962), a terminal cancer victim who euthanizes himself—an act simulated onstage by Fonda, his back to the audience, as “a private act of empathy and remembering.”

The psychological dynamic at work here is of sufficient depth to warrant its place in McKinney’s lengthy consideration of suicide in Fonda’s life, which concludes that it was the actor’s art that saved him, and just barely, from succumbing to the despair that claimed so many close to him. But the emphasis on remembrance also accords with McKinney’s political sense of Fonda, why he remains important despite his manifold flaws and personal limitations:

After Young Mr. Lincoln, no actor is more identified with the presidential role than Fonda, and Fonda is inconceivable as any other kind of president than Lincoln—that bearer of burdens who, when he looks past the faces of ordinary folk, sees eternity looking back. Lincoln was one of the very few men to ever suggest this depth in our White House, and Fonda is fit to represent him, because damned if he doesn’t act like he knows some of that burden.

This passage is one of McKinney’s attempts to reclaim Fonda for the national mythos, to depict him as an alternative ideal: a man with a mournful appreciation of the past and its costs, rather than a heedless orientation toward the future. If this sounds like too much of an abstraction, perhaps too neatly virtuous, it loses some of its generality by serving as twenty-first-century critique—specifically of Bush-era jingoism. Just before the passage cited above, McKinney finds in Fonda’s performance as the president in Fail-Safe (1964) “a heroism that hates to kill, that instead of boasting ‘Bring it on’ asks, ‘What do we say to the dead?’” Such a display of strength without swagger, of a sense of obligation reaching beyond the needs and desires of the present, rejuvenates out of history and myth something of the unreachable Lincoln ideal. In some of Fonda’s best moments on-screen we are reminded to remember that ideal, if only as an ephemeral film image, as a ghostly trace.

James Gibbons is associate editor at the Library of America.