In Chris Kraus’s novel Torpor (2006), the protagonist Sylvie remarks to an all-male group of intellectuals, including her husband, that there are no women on the list of writers they’re putting together for a cross-cultural literary tour. No one knows any of the “dowdy” lesbians that Sylvie has put forward, so they settle on Kathy Acker. There is little debate. “Of course, thinks Sylvie, if there has to be a woman, Acker would be it. Her books seduce and challenge heterosexual men; her photos just seduce them. . . . Why could the famous artist men be friends, the women just competitors? Was sex still the only passport to success if you were straight and female?”

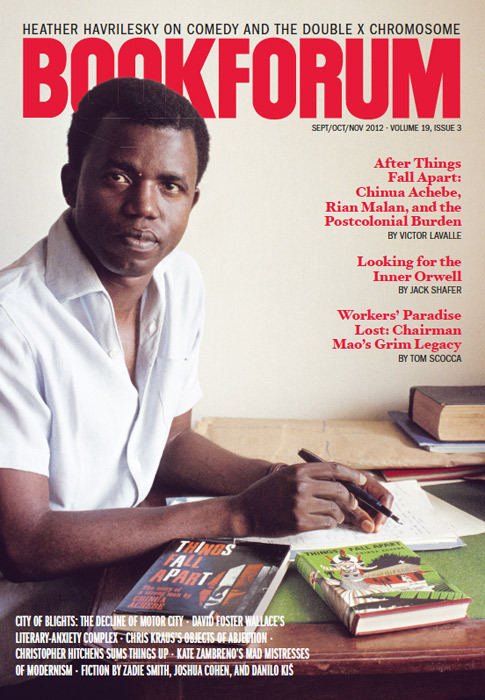

Acker, Sylvie decides, understood that artistic success is based on creating a myth, and “female myths don’t run in groups”—they come as tokens. For the past thirty years, Kraus has dedicated herself to making room for more than one woman to be onstage. In 1990, she founded the Semiotext(e) Native Agents series to publish literature by women—including Cookie Mueller, Eileen Myles, Fanny Howe, Lynne Tillman, and Acker herself—that crossed poetry, fiction, criticism, and theory. (Before Native Agents, Semiotext(e) had only published men.) Female subjectivity was not just worthy of being theorized; for the Native Agents, it was already a body of theory.

In 1997, Kraus published I Love Dick, her first novel, under the Native Agents imprint, followed by Aliens & Anorexia (2000), Torpor, and the newly released Summer of Hate. All four feature disarmingly direct female narrators, who relate the author’s own thoughts, feelings, and raw experience. At the time of Aliens, Kraus explained that she didn’t consider her work memoir, because memoir is retrospective; she writes in the “right now” of the present tense. Her characters fire off love letters, read books, complain about still-unfinished work, feel shame. A memoir would bring closure to life, but she tells it now, as living, with the author a “channel” for the culture: “It’s passing through my body.” Having sharpened the knife of observation on the whetstone of their own chronic insecurities, Kraus’s narrators dissect the art world, intellectual fashions, and the fall of communism. Underlying everything is a fascination with failure—failure to impress, failure to be noticed.

Kraus came by this interest honestly. Born in New York and raised in New Zealand, she moved to Manhattan in the 1970s and forced a place for herself in the rotten East Village. (Her novels note the gentrification of the city and also the changes in women’s fashion—back when she was topless dancing, the women wore shapeless, baggy clothes offstage.) In the early ’80s she began making films and videos. She filmed herself screaming in a snowstorm in her underwear and called it a comment on Artaud. She made a 16-mm film about religious conviction whose shots she later described as “bulimic.” This work was not popular. In the late ’80s she married Sylvère Lotringer, a professor at Columbia who had founded Semiotext(e) in 1974. (The two first met for weekly s/m sex dates that transitioned into a “relationship.”) Shut out of film festivals and denied grant money, she spent her nights being ignored at dinner parties by fatuous intellectuals. Put off by what she dubbed “Good Girl Academics,” she refused to call herself a feminist; her goal was “transcending” gender. Eventually she decamped to an upstate farmhouse, where she warded off suicide by homesteading and caring for her dachshund. (She now lives in Los Angeles.)

Kraus was a funny kind of failure—the kind who could get a film into Nan Goldin’s hands, but couldn’t make her like it. In Torpor she reflects on the problem. “Her movies were unfashionable,” she wrote. “Messy, inchoate, intensely private spirals of association. Too punk to be a formalist, too intellectual to be underground.” She wanted something—to screen her work, to be accepted, to be acknowledged for the work she did that Lotringer took credit for—but unlike the feminists she rejected, she didn’t want for a class or for a social movement. She wasn’t a joiner. She wanted for herself, and for her friends.

Her marriage drifted into a psychically intimate but sexually passionless rapport, and when she happened to meet cultural critic Dick Hebdige, she fell into a passionate obsession that she insisted on calling love. Two hundred letters and one threatened lawsuit later, Kraus published I Love Dick, a manic masterpiece, a mix of narrative, letters, critical theory, art history, and biography that revels in masochism as a form of antagonism. This first novel was her best; the unique authority of her voice was most formidable when she was feeling her way toward it. “For years I tried to write but the compromises of my life made it impossible to inhabit a position,” Chris writes to Dick. “And ‘who’ ‘am’ ‘I’? Embracing you & failure’s changed all that cause now I know I’m no one. And there’s a lot to say . . .”

Her new novel, Summer of Hate, explains the method:

Having no talent for making shit up, [Catt] simply reported her thoughts—an enterprise that seemed, to her, squarely within a tradition espoused by Michel and his friends, philosophers who held endowed chairs at elite universities, and traveled the world. And to a certain extent she’d succeeded, but as a female whose thoughts arrived mostly through the delirium of daily life. She saw no boundaries between feeling and thought, sex and philosophy. Hence, her writing was read almost exclusively in the art world, where she attracted a small core of devoted fans: Asperger’s boys, girls who’d been hospitalized for mental illness, assistant professors who would not be receiving their tenure, lap dancers, cutters, and whores.

Kraus’s performance of authenticity is sincere and biting, self-disparaging and self-aggrandizing, ambivalent and proud. Note the classic American claim to transparency: Catt is “simply reporting” her thoughts, as if there were anything simple about being an Emersonian eyeball. And careful with that phrase, “as a female whose thoughts arrived mostly through the delirium of daily life”: “Daily life” is the time of thinking and feeling, of intellect and body. It includes illness and crying, sexual degradation (“All acts of sex were forms of degradation”) and the trial of being a “Serious Young Woman,” American flags and theory and e-mail.

When no one wanted her films, Kraus refused to go away; when she didn’t want to fail as an artist anymore, she started writing about failure. She insisted on being seen for being no one and nothing. This was an easier sell than video art. Sex is not, as Sylvie worried, the only passport to success, but a woman seeking art-world attention must be seductive somehow. In Kraus’s work, it is the dysfunction itself, and her enervated, joyless, hollow voice, that pleasures. The powers of horror to disgust or repulse are so often defanged by the culture’s hunger for female brokenness. And it is there, in Kraus’s contention that her myth is not singular like Acker’s but exemplary of the female condition, that the real horror lies.

• • •

In I Love Dick, the character Chris explains that the philosophy that “art supercedes what’s personal” is one that “serves patriarchy well.” One formula has it that life is personal and art transcendent; for Kraus, art is personal and life isn’t. Life’s impersonality creates the possibility for personal art, art that could be intimate and embodied and belong to someone: It was by examining her failure from the outside that Kraus made herself into a character. But if life isn’t personal, then success isn’t, either, and that brings its own brittleness. Catt, a professor and critic who makes money flipping real estate, remembers last year’s book tour:

After coming back from the tour, she’d played a cameo role in a friend’s video art piece: a Druid priestess fellating a tree, in a blonde wig and long purple dress cut down past her tits. Wasn’t she getting a bit old for this? A reviewer of her last book accused her of giving him “blue balls.” If only she’d attended an Ivy League school, her work might be read as serious cultural criticism, not the punch line of the last dirty joke in the world. But what was dirty?

The work is misunderstood, but it’s also stale; she’s forty-five and she’s getting tired. The same anecdotes, quotations, and figures keep popping up across Kraus’s writing, novel to novel, in essays and art criticism. (For someone with little use for psychoanalysis, Kraus has been more than driven by the compulsion to repeat.) The passage ends by asking “if new dreams were even possible.”

Summer of Hate is about the risks and limitations of new dreams. It opens with Catt on the run from Nicholas Cohen, a dominant she met on a BDSM website. Nicholas had seemed rich and charming (Catt was pleased that he reported to have “considerable experience with the dynamics of outwardly assertive independent female personas—executives and other types—seeking a path of surrender and loss of control to achieve an essential balance which is central to real self-fulfillment”) until he wanted Catt to sign over her financial assets. An hour online revealed that the Internet presence that he promised was “verifiable” was actually a fraud: one vanity site leading to another, all backing up one another’s lies. Delusional, Catt decides that Nicholas wants to kill her. She heads to Mexico.

Her next stop is Albuquerque, where she’s invested in some slummy apartment buildings. It’s there that she hires Paul Garcia to manage the units. An alcoholic and ex–oil-truck driver recently released from prison after a crack and booze bender found him running up charges on Halliburton’s credit card, Paul is trying to put his life back together. They become lovers: He shows her “real” America; she teaches him the word precariat. Catt is signing Paul’s tuition checks when an old charge resurfaces and he’s locked up again.

Catt is a witness to the contemporary American scene: the housing bubble and crash, Southwest exurbs, the prison-industrial complex. She is ridden with class guilt and bound by obligations; her relationships with men are credit transfers, bills that she’s incurred. Nicholas wants her money, and so does Paul, and there’s also Tommy, her queeny assistant, whose minor embezzlements she lets slide because he knows about her tax shelters. Where Kraus’s protagonists used to sleep with critics, Catt sleeps with her lawyer. Instead of meditating on overlooked feminist artists, she thinks about Abu Ghraib and Joe Arpaio, the Phoenix sheriff who humiliates his prisoners by dressing them in pink and parading them through the streets.

Organized into twelve chapters like the twelve steps of recovery, Summer of Hate is a story of structural injustices. In good paranoid fashion, Catt, and the novel itself, connect everything to everything else. Catt’s psychological distress seems intended as a manifestation of cultural psychosis, but her diagnosis of the political culture is cartoonish—she donates the taxes she avoids paying to Amnesty International—and the novel’s knowledge of Christianity feels snatched from the evening news. The world of the novel is so academically small that its despair comes to seem small, too. “Apparently everyone outside the art world has either lived in a van or been incarcerated,” Catt thinks when she hears the life stories of her construction crew. “None of these people see any connection between their sad, shitty stories.” This is meant to be funny, but it’s the joke of an uncurious art-world insider. It says as much about Catt’s myopia as it does about poverty.

Summer of Hate refuses fiction’s traditional commitments to character development and epiphany: Catt does not learn from her mistakes. Paul experiences a political and intellectual awakening, but Catt makes no adjustments and has no insights. Heavy reliance on prolepsis makes clear that Catt is the one in jail, sentenced to exploitation and extortion and passivity. The repetition of “will”—“Catt will discover . . . Tommy will threaten . . . Her father will offer . . .”—accumulates irony. Ultimately the narrative forecloses the possibility of self-knowledge. “She’ll try to connect” the future to the past, “but she’ll fail,” one passage informs us. “The words are too heavy because they refer to things that no longer exist.” Subjection is a property of her character, as if she, like Paul, has abdicated her being to a higher power. Paul has his record and she has her words, but there is no one to hire to clear her from those; her life forms a kind of net, or trap, that defeats her. “Then he calls Catt,” the novel ends. “He still has her number.”

• • •

The new dream animating Summer of Hate is that it could be possible to speak about others—that the “impersonal” could be achieved through another voice. There were no characters in Dick or Torpor or Aliens—only symptoms, walking and talking, reflecting to the female protagonist something about her needs and desires. In Summer, Catt isn’t remembering her youth; she’s working on a project about nineteenth-century reformers. “Maybe, Catt thinks, she could do something else with these lives. Something maybe not quite academic, but less empty to her than art writing. Perhaps, instead of her own, she could use these other lives to tell a story?”

The novel attempts to create a character in Paul, although the passages from his perspective are often forced and awkward. His conversion is intangible and invoked for convenience, and by the time he’s back in jail he has long become a cipher for Catt’s weaknesses and attraction to men who abuse her. Kraus’s strength as a writer is not in imagining others’ experience, and it isn’t even in analyzing her own—it’s claiming her own as enormous. Her “channeling” is an act of intellectual biography. “We are our influences,” she declared in the essay “No More Utopias,” and some of the best passages of her writing are readings of, allusions to, quotations from, and reflections on her lineage: Simone Weil, Paul Thek, R. B. Kitaj, Hannah Wilke, Lydia Lunch. Her experience is a small bit of matter that attracts mass in the form of genealogy.

Kraus’s question in Dick—“Why does everybody think that women are debasing themselves when we expose the conditions of our own debasement?”—does not suggest that abjection is the basis of political power, something that could be transferred or shared. Her narrators want something else. They want to look at themselves and to be taken seriously for doing so. Sometimes that makes art; sometimes it is only a style of avoidance. Kraus talks about other stories, but she can’t tell them. Demanding recognition, her novels do not recognize anything outside her own mind. An eternal fact of authorship is thereby reduced to something literal. This has been an important experiment, but it’s reaching its limits. Kraus can take a trip to the Southwest, but she can’t think anything new. Channeling isn’t creating. Maybe this is the real meaning of abjection. Maybe it’s not about sex at all, but about the degradation and debasement of being nothing but what you’ve always been.

Christine Smallwood is a doctoral candidate in English at Columbia University.