A compelling mixed review is a devilishly difficult thing to write. Raves and pans have obvious, inherent drama, as they get to trumpet great successes or bemoan deplorable failures. But a mixed review must share the less exciting news that something is good, not great—or that, while the work in question mostly misses the target, it is not entirely without interest. Many mixed reviews thus read like so much wishy-washy indecision.

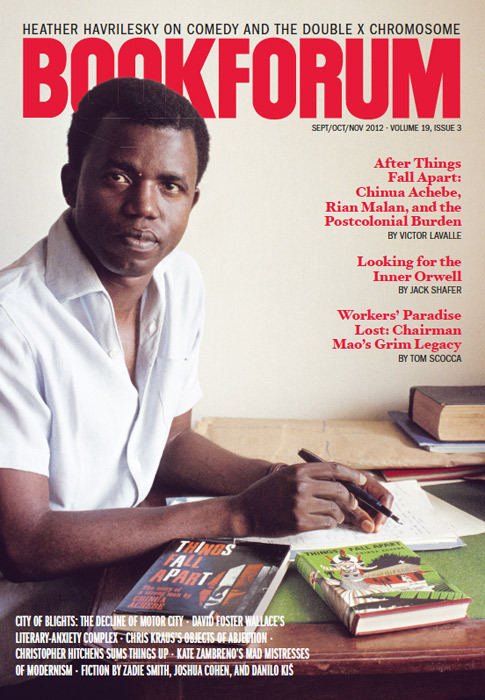

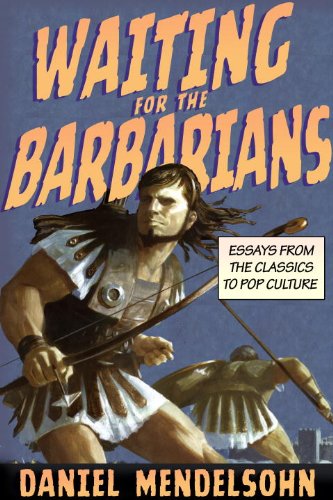

But the most compelling reviews in Daniel Mendelsohn’s very good new collection of them, Waiting for the Barbarians, are decidedly mixed. Regular readers of the New Yorker, the New Republic, and, especially, the New York Review of Books know that Mendelsohn is a formidably learned writer, a classicist who has written a scholarly study of Euripides, translated C. P. Cavafy, and published memoiristic books about the Holocaust and gay life in America, and also knows French. They may have noticed, too, that Mendelsohn always does his homework. Reviewing Richard Howard’s 1999 translation of The Charterhouse of Parma for the New York Times Book Review, for instance, Mendelsohn speaks knowledgeably of translations from 1901, 1925, 1958, and 1997.

Even more important, Mendelsohn brings to his subjects both an attentive eye and a sympathetic mind. One never finishes one of Mendelsohn’s reviews feeling like he had it in for, say, Jonathan Franzen, or Anne Carson, or Matthew Weiner—to cite three writers who get dinged harder than most in the new collection. He expresses considerable admiration for Franzen and Carson—though not so much for Weiner, the creator of Mad Men, which Mendelsohn describes as “a soap opera decked out in high-end clothes” and dismisses as a fad.

Mendelsohn usually begins his reviews with a longish introduction that builds to a problem that must be solved. He then withholds the solution, so that you must keep reading to get the answer. That pan of Mad Men, for instance, asks why critics and viewers have responded so rapturously to a show that he deems “weak,” “shallow,” “incoherent,” and “smug.” After proposing a few plausible explanations, he says that the correct answer is none of these, but “something else entirely, something unexpected, and, in a way, almost touching.” Three thousand words later, he explains what that “something else” is: We all like to see what our parents were like before we were born. (This is not the most convincing piece in the book.)

There’s a subtler example of this old-fashioned and very effective technique in Mendelsohn’s surprisingly interesting take on the James Cameron blockbuster Avatar. I say “surprisingly” because one of the mild disappointments of Mendelsohn’s previous collection, How Beautiful It Is and How Easily It Can Be Broken (2008), was the seemingly dismissive and even curmudgeonly attitude he took toward populist entertainments like 300 and Kill Bill, Volume 1. In hindsight, these were perhaps just the wrong kinds of movies for Mendelsohn. His consideration of Avatar in the context of Cameron’s career—and, in particular, the director’s finally overwhelming love of technology—is one of the best essays here. (The very best also involves Cameron: It’s a look at the now-century-old fascination with the Titanic—a fascination that has gripped Mendelsohn since childhood.)

While that previous collection contained several essays about movies, only two appear in this one. The second is about Aleksandr Sokurov, a director most famous for Russian Ark, his one-shot fantasia about the Hermitage Museum and Russian history. Mendelsohn’s essay about him is typically thoughtful and thorough—and atypically flat. In trying to understand what the piece was missing, I realized that the review was a rave: Mendelsohn loves Sokurov’s work, and so he has no knotty problem to present us with. In the spot where he’d normally grab the reader with an intellectual dilemma, Mendelsohn writes that Sokurov’s “preoccupation with dreams serves what may be his real interest: history.” An entirely plausible thesis, and one Mendelsohn argues for persuasively, but not nearly so grabby as when, for instance, he says that Susan Sontag failed to understand what century her consciousness truly came from, and that this failure “explains a great deal about both the strengths and weaknesses of her work, and also the strange fascination that she exerted.” (Five thousand words later we learn she truly belonged to the eighteenth century, and not, as Sontag apparently believed, the nineteenth.)

That lengthy essay about Sontag, written in 2009, just after the first volume of her journals was published, closes this book, and it is, if not the best essay here, probably the most engrossing one—at least for those readers, like me, who are fans of Mendelsohn’s work and have spent some time trying to pin down his critical sensibility. In diagnosing Sontag’s strengths and weaknesses as a critic, Mendelsohn inevitably hints at some of his own. Sontag, he concludes, was torn between various extremes. She was—to quote, as Mendelsohn does, her description of Don Quixote—“a hero of excess,” a self-described “partisan” and “enthusiast” who misunderstood her real value as a writer, fancying herself finally a novelist, rather than a critic.

Mendelsohn suffers from no such confusion about what he brings to the table. And, again unlike Sontag, he is neither a partisan nor an enthusiast. Five-thousand-word love letters require a kind of wild passion that seems foreign to Mendelsohn’s coolly intelligent prose. When he trumpets Sokurov, or Stendhal, or the underappreciated novelist Antonio Muñoz Molina, he actually becomes something of a bore. Give him a flaw to diagnose, on the other hand, a strange blemish on a heretofore sterling surface—say, the new confusion evident in The Stranger’s Child about whether its author, Alan Hollinghurst, stands with “the ‘queer’ outsiders or the establishment”—and Mendelsohn will solve it with Sherlockian élan, giving his answer the satisfying structure of a Conan Doyle story. Mixed reviews, in other hands often as dull as ditchwater, become intellectual detective stories, and Mendelsohn provides illuminating, elegant solutions.

David Haglund is a writer and editor at Slate.